Smoking is one of the main causes of chronic lung disease (Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP), 2017). As more people are diagnosed with COPD, not only is the financial burden placed on health services increasing, but a rise in workload has been noted, particularly in primary care settings where a large proportion of COPD care is delivered (British Lung Foundation, 2017; Public Health England (PHE), 2017).

Hand-held vaping devices or e-cigarettes began to emerge as an alternative nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) around 2015. As e-cigarettes do not contain tobacco and other harmful toxins found in cigarettes, it is believed they help reduce lung disease and smoking-related deaths (Hartmann-Boyce et al, 2020). With the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance (2018; 2021) and the RCGP (2017) recommending healthcare professionals (HCPs) discuss the use of e-cigarettes as a means to quit smoking, their popularity has risen. However, there is now a rising trend of smokers using e-cigarettes in addition to conventional cigarettes in the long-term (Action on Smoking and Health (ASH), 2021).

While there is a belief that long-term use of e-cigarettes may prevent a full relapse back to conventional cigarettes, there is insufficient safety data available to establish accurately the level of risk associated with their use (Marczylo, 2020). Adverse effects or harms reported to The Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MRHA) between May 2016 and January 2020 totalled 245 (PHE, 2020). Research studies supporting the concerns of many HCPs have reported users experiencing headaches, mouth and throat irritation, coughing and nausea (Hartmann-Boyce et al, 2020), with spirometry studies identifying increased airway resistance with decreased airway conductance (Palamidas et al, 2017), and decreased forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) following short-term use (Ferrari et al, 2015). Despite such concerns, clinical guidance suggests HCPs advocate for the use of e-cigarettes based on the belief that while they are highly unlikely to be risk-free, they are substantially less harmful than conventional cigarettes (RCGP, 2017; NICE 2018).

While it is clear from current health policy and guidance that the use of NRT and e-cigarettes should be supported by HCPs, their promotion remains controversial (McRobbie et al, 2014). HCPs need to feel confident they have access to information supporting effective smoking cessation methods while minimising any potential harms. This literature review was undertaken to determine whether the promotion of e-cigarettes is an appropriate intervention to improve lung health and reduce exacerbations in patients with existing COPD.

Methods

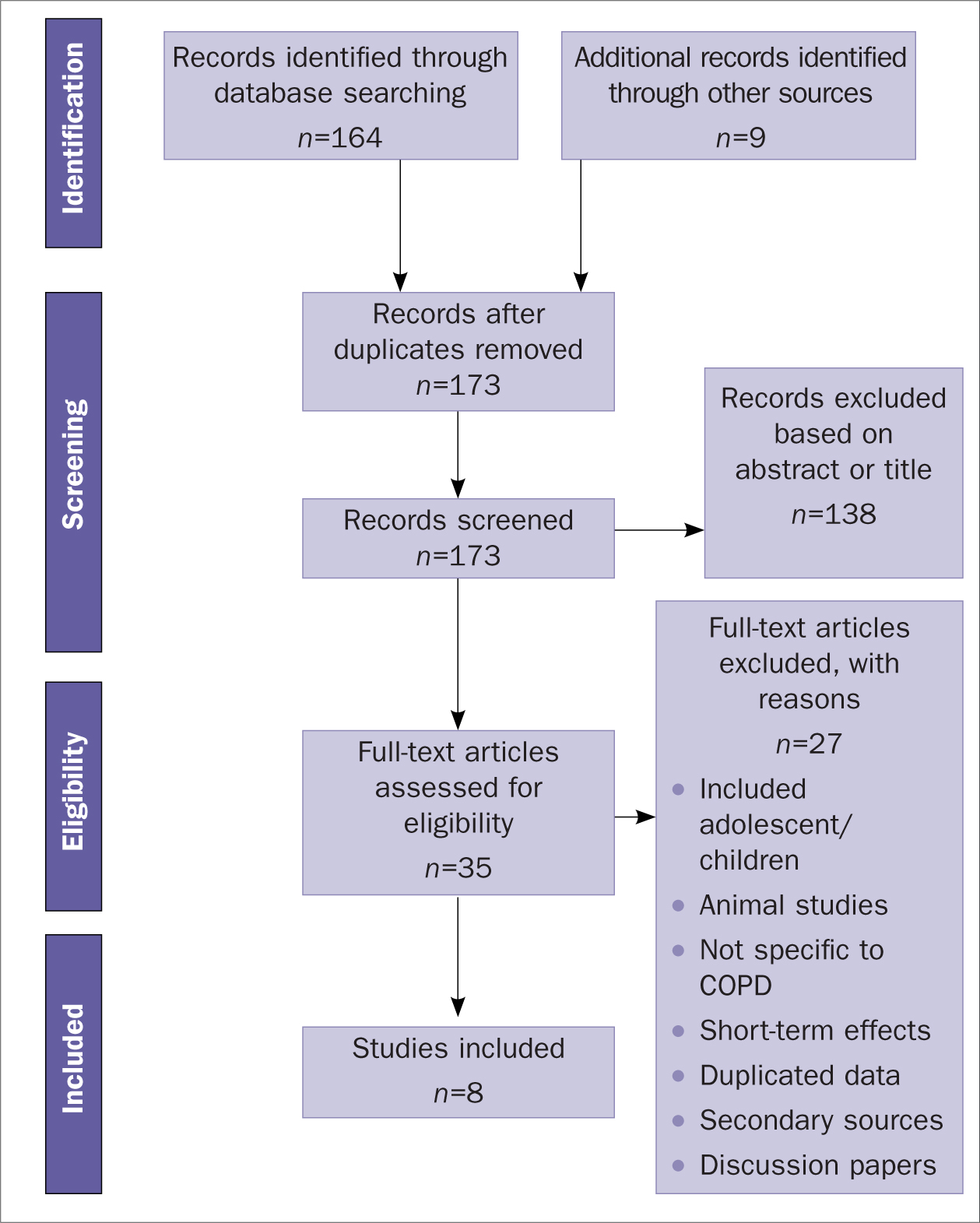

This systematic review focused on identifying quantitative empirical research, providing numerical data detailing the effect of e-cigarette use on pulmonary health outcomes. The PICO model (Fineout-Overholt and Johnston, 2005) was used to identify search terms to refine and focus the searches. As e-cigarette use is prevalent worldwide, terms used to describe the product in other countries were included. Searches of CINAHL and MEDLINE databases identified 164 articles of interest; a further nine articles were identified from references and citations. Application of explicit inclusion and exclusion criteria facilitated the removal of 138 papers (Table 1). Details of the selection process applied is demonstrated by the Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) diagram (Figure 1).

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

In order to provide a robust, critical analysis strategy for the review, selected papers were appraised for strengths and weaknesses using recognised appraisal tools provided by Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP, 2021). Each study was examined to ensure a robust and clear design. Data collection and sampling methods were scrutinised, and the data analysis and statistical tests applied by the authors were critiqued. As each paper was analysed, common themes were noted. A thematic analysis, identifying and examining patterns arising, was used to bring together the key findings in a logical manner.

Findings

1. Use of e-cigarettes to reduce consumption of conventional cigarettes

Four studies (Polosa et al, 2016; 2018; 2020; Bowler et al, 2017) suggest e-cigarette use allowed participants to significantly reduce or stop smoking conventional cigarettes. Of the participants, 93% in the COPDgene study and 87% from the SPIROMICS arm, acknowledge they used an e-cigarette to reduce consumption (Bowler et al, 2017). While it is important to highlight that participants in the other studies (Polosa et al, 2016; 2018; 2020) were chosen specifically due to their motivation to achieve cessation, e-cigarette use successfully led to complete abstinence in 59% of participants at year three (Polosa et al, 2018); however, this figure had reduced to 45% at year five (Polosa et al, 2020). Despite the lack of abstinence in the remaining participants, the authors acknowledge e-cigarette use led to a significant reduction in consumption overall. As 90% of participants reported reduced nicotine consumption from 12–18 mg/ml to between 3–9 mg/ml, reduced nicotine dependency is likely to be a contributing factor (Polosa et al, 2016; 2018; 2020). However, Bowler et al (2017) suggests there was less evidence to support e-cigarette use being associated with complete cessation, reporting a relapse rate of 38% at year five. In contrast to this, the authors report the figure for relapse in non-e-cigarette users was much lower at 3.5%.

Table 2. Studies included in the review

| Author | Country | Design | Method | Sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polosa et al (2016) | Italy | Retrospective cohort | Case note review following daily use of an e-cigaretteMeasured by:

|

48Diagnosis of COPD |

| Bowler et al (2017) | USA | Prospective cohort | Two separate studies analysed e-cigarette and conventional cigarette use over 5 years

|

COPDgene = 10 294SPIROMIC = 2982 |

| Higham et al (2018) | UK | Experimental laboratory | Measurement of CXCL8 and IL-6 in bronchial epithelial cells taken via bronchoscopy from patients exposed to e-cigarette vapour and cigarette smoke | 8Healthy non-smokers = 3Diagnosis of COPD = 5 |

| Polosa et al (2018) | Italy | Prospective cohort | Case note review following daily use of an e-cigaretteMeasured by:

|

44Diagnosis of COPD |

| Bozier et al (2019) | Australia and UK | Experimental laboratory | Measurement of cytotoxicity and CXCL8 release in the airway smooth muscle cells of people with or without COPD exposed to 18 mg/ml nicotine tobacco, 0 mg/ml nicotine tobacco and 0 mg/ml nicotine menthol | 22Diagnosis of COPD = 9 |

| Xie et al (2020a) | USA | Prospective cohort | Data taken from the Behavioural Risk Factor Surveillance System 2016 and 2017 – a US-wide surveyAnalysis of self-reported incidence of COPD in e-cigarette users | 891 24215 986 dual users115 189 current smokers245 973 ex-smokers8876 current e-cigarette users who were ex-smokers3912 current e-cigarette users who never smoked501 306 never users |

| Polosa et al (2020) | Italy | Prospective cohort | Case note review following daily use of an e-cigaretteMeasured by:

|

39Diagnosis of COPD |

| Xie et al (2020b) | USA | Cross sectional cohort | Data taken from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) study – a US wide survey.2013–2018Analysis of self-reported incidence of COPD in e-cigarette users. | 21 61814 213 – non smokers2076 – former e-cigarette users2329 – current e-cigarette users |

2. Dual use of e-cigarettes and conventional cigarettes

Patients with COPD commonly report dual use of e-cigarettes and conventional cigarettes (Polosa et al, 2016; 2018; 2020; Xie et al, 2020a). Polosa et al (2016; 2018; 2020) report 45% of participants disclosed use of an e-cigarette alongside smoking cigarettes. Although the term dual use is not quantified, authors reported that dual use facilitated a reduction in conventional cigarette consumption of at least 80% in these participants. For those able to reduce their consumption of conventional cigarettes, dual use may be associated with improved health outcomes including reduced exacerbation rates and improved COPD assessment test (CAT) scores (Polosa et al, 2016; 2018; 2020).

While for some, using an e-cigarette to reduce consumption may improve pulmonary outcomes, other dual users may experience higher nicotine dependency and consumption when compared to conventional smokers (Bowler et al, 2017). As dual users continue their exposure to combustible tobacco, they also increase their exposure to carcinogens and other toxins associated with other poor pulmonary outcomes (Xie et al, 2020b). Exposure to increasing levels of nicotine may be associated with increasing cytotoxicity within airway smooth muscle cells, potentially worsening disease outcomes (Bozier et al, 2019).

3. E-cigarette use to alleviate and improve symptoms

Improvement in symptoms was reported in three papers (Polosa et al, 2016; 2018; 2020). Authors noted an increased ability to perform physical activities, improved CAT scores and downgraded GOLD staging upon review (Polosa et al, 2018; 2020). Although no changes in spirometry were noted at year three (Polosa et al, 2018), improvements in lung function were observed following spirometry at year five (increase of 23.3 mL in FEV1) (Polosa et al, 2020). A 50% reduction in exacerbation rates among sole e-cigarette users was also observed, with the mean annual exacerbation rate of 2.3 recorded at baseline, reducing to 1.1 at year five, and from 2.6 to 1.6 in dual users (Polosa et al, 2020).

Box 1. Further reading and useful information

- Action on Smoking and Health (ASH) a public health charity that works to eliminate harm caused by tobacco. https://ash.org.uk/home/

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Stop smoking interventions and services [NG92]. 2018. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng92

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in over 16s: diagnosis and management [NG115]. 2018. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng115

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Tobacco: preventing uptake, promoting quitting and treating dependence. 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng209

- Public Health England. Vaping in England: an evidence update. 2019. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/vaping-in-england-an-evidence-update-february-2019/vaping-in-england-evidence-update-summary-february-2019

4. Association between e-cigarette use and development and progression of COPD

E-cigarette use may be associated with worsening respiratory health and disease progression (Bowler et al, 2017; Xie et al, 2020b). Although participants of some studies (Polosa et al, 2016; 2018; 2020; Bowler et al, 2017) were recruited noting an already heavy smoking history, and fair or poor general health relative to never-smokers, one study identified a 40% increased risk of developing a respiratory condition with current e-cigarette use. This persisted even after adjusting for smoking history and other important confounding variables (Xie et al, 2020b). Evidence suggests progression may become more pronounced in established daily use and with increasing age (Xie et al, 2020a; 2020b). While e-cigarette use is associated with self-reported COPD diagnosis in ex-smokers, it has also been noted in never-smokers (Xie et al, 2020a), suggesting sole e-cigarette use may be associated with the development and progression of disease regardless of smoking history.

5. Effects of inhaling e-cigarette vapour on pathological processes associated with COPD

Inhalation of e-cigarette vapour triggers pathological processes associated with worsening COPD and exacerbation. A history of ever using an e-cigarette was significantly predictive of COPD exacerbations (p=0.01) (Bowler et al, 2017). Inhalation of e-cigarette vapour and cigarette smoke has been associated with increased release of IL-6, CXCL8 and dampened poly I:C-stimulated C-X-C. Such processes are linked to reduced antimicrobial responses and increased inflammation, heightening the likelihood of COPD exacerbation (Higham et al, 2018; Bozier et al, 2019). Worsening responses, increased toxicity and greater CXCL8 production were noted in cells taken from patients with existing COPD compared to the cells taken from healthy subjects, suggesting that patients with COPD are at higher risk than those without a diagnosis (Bozier et al, 2019). Levels of nicotine in the e-cigarette were also noted to increase cytotoxicity; however, CXCL8 increased irrespective of the presence of nicotine in the vapour (Bozier et al, 2019).

Discussion

The process of vaping mimics the experience of smoking. For this reason, e-cigarettes are believed to assist the user to decrease consumption. These findings reflect those documented by ASH (2021) who suggest many users reduce their cigarette consumption from heavy to light use. In NICE (2018) guidance, which suggests HCPs advocate for e-cigarettes based on the belief they are substantially less harmful is considered, any reduction in consumption would be advantageous and viewed as a positive step towards reducing symptoms and morbidity.

E-cigarette use may also allow an opportunity to lower nicotine, reducing dependency. However, because many smokers are hooked on the ritual and habit of the act, total abstinence rates remain low. This suggests that a statement made by the Department of Health and Social Care (2021) claiming most adults use e-cigarettes to help them quit smoking altogether, may be somewhat unfounded in this particular cohort. In cases where abstinence is not achieved, many continue to use e-cigarettes long-term, alongside conventional cigarettes (ASH, 2021). Attar-Zadeh (2019) argues that people smoke due to their addiction to nicotine; however, it is the harmful by-products of tobacco consumption that will lead to their death. It could therefore be suggested that HCPs consider the promotion of e-cigarettes over conventional cigarettes as appropriate, in an effort to achieve some health improvement and reduce harms. However, the literature reviewed suggests dual users with COPD may have higher nicotine dependency, thereby increasing their overall consumption and exposure to harmful cytotoxic ingredients.

The hallmark of COPD is the presence of inflammation in pulmonary tissues and cells (Sharifabad, 2021). Inflammatory changes seen in these studies are consistent with those known to narrow airways, increase mucus production and reduce alveolar function. In addition to inflammation found in pulmonary tissues, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) (2021) suggest systemic inflammation may also occur, contributing to worsening general health and the initiation and progression of other co-morbidities such as cardiac, metabolic, and skeletal disease.

While there is evidence to suggest e-cigarette use may assist the smoker with COPD to improve symptoms and lessen exacerbations through reduced consumption, there are other factors, such as existing severity of disease, which seem to influence individual success. Gee et al (2021) argue that even if smoking was completely eradicated, many lives will still be lost in future years due to pulmonary damage, which has already been sustained by smokers. Consequently, promotion of e-cigarettes by HCPs may simply allow a new opportunity for smokers with COPD to become addicted to a different nicotine-containing product, facilitating further disease progression.

While it is important to recognise and acknowledge positive findings from this review, it remains difficult to conclude e-cigarette use may halt disease progression. COPD diagnosis reported in never-smokers suggests e-cigarettes use should be viewed as harmful, facilitating the development of pulmonary disease. If COPD is already present in individuals who choose to vape, HCPs may assume vaping will continue to facilitate worsening symptoms, leading to poor outcomes and increased morbidity. The view that e-cigarette use will continue to harm individuals who choose to pursue the habit seems not without solid foundation, thus making it challenging for HCPs to support their use as a safer alternative to conventional cigarettes as suggested by current guidance (NICE, 2021).

As most subjects in the studies reviewed already had a diagnosis of COPD, any examination of pulmonary outcomes remains challenging. It must be recognised that establishing and separating the degree of pulmonary damage sustained from e-cigarette use from any existing damage from conventional use is difficult to do with any degree of certainty. Despite this, Gotts et al (2019) argue that as the majority of studies examining e-cigarette use have been performed using healthy subjects, clear links between their use and inflammatory diseases have already been established. As such, concerns regarding the influence of any prior diagnosis may be unfounded, with a plethora of evidence suggesting e-cigarette use promotes disease progression and poor health outcomes supporting any argument regarding causation.

Conclusion

The findings of this review suggest e-cigarettes may help people with COPD to moderate conventional cigarette consumption. In doing so, improvements in symptoms may result. However, users who report high consumption, or continue to vape, with or without additional conventional cigarettes, may experience development and progression of disease. For those with an existing diagnosis of COPD, e-cigarette use appears to intensify advancing disease, increasing the likelihood of exacerbation. Pathological processes such as inflammation and reduced antiviral responses seem to be triggered by e-cigarette vapour in a more exaggerated way than that seen in healthy lung tissue, worsening outcomes for those with pulmonary disease.

While this review is unable to make any firm statements regarding just how safe e-cigarettes are for use by patients with pre-existing chronic lung conditions, it is clear their use is not harm free. Although medical research is still in its infancy, there is a consistent and expanding catalogue of evidence to demonstrate a link between chronic use and the development of COPD symptoms, exacerbations and disease progression. Despite the fact that there is a body of literature suggesting they may have a positive role in smoking cessation and/or reduction, little is known about the long-term effects.

It therefore remains to be seen whether the negative outcomes associated with e-cigarette use in this cohort will influence policy makers to consider the revision of current guidance, supporting HCPs to discourage their use. What is clear is that all HCPs should cease to be ambivalent and equip themselves with knowledge regarding e-cigarette use, in order to accurately inform and advise smokers and those with existing respiratory disease, about the potential harms.

KEY POINTS:

- E-cigarettes may help patients with COPD to reduce consumption of conventional cigarettes

- Dual use of e-cigarettes and conventional cigarettes is common among patients with COPD

- E-cigarette use may help alleviate and improve COPD symptoms in some smokers; however, e-cigarettes may be associated with development and disease progression in others

- Inhalation of e-cigarette vapour triggers pathological processes associated with worsening COPD and exacerbation

CPD reflective practice:

- How would you approach a consultation regarding the risks of smoking and its impact on COPD?

- How confident are you about discussing nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), including the use of an e-cigarette to achieve smoking cessation and/or reduction?

- How will this article change your clinical practice?