Endometriosis is a gynaecological disorder that is estimated to affect between 2 and 10% of women in the general population, but up to 50% of women with infertility (European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology [ESHRE], 2013). However, the true prevalence is difficult to estimate due to the condition's uncertain and enigmatic nature. Endometriosis is complex and multifactorial with evidence suggesting that care can be delayed due to health care practitioners' lack of awareness and understanding of the condition, leading to a reported average delay in diagnosis of 5–8.9 years (Culley et al, 2013). In 2017 and 2018 the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) released guidelines on managing suspected endometriosis and accompanying quality standards for prioritising care improvement (NICE, 2017a; 2018). Nurses working in primary care services can support women with suspected endometriosis by having an understanding of this condition and the range of presenting symptoms to facilitate a timely referral to specialist services.

This article provides an overview of endometriosis and identifies the role of the practice nurse in supporting women with this diagnosis through their patient journey, referencing best practice from the NICE guidelines, quality standards and accompanying decision aids.

What is endometriosis?

Endometriosis is an oestrogen-dependent chronic condition where endometrial tissue forms lesions outside the uterus (Figure 1), which induce a chronic, inflammatory reaction (Dunselman et al, 2014). While endo-pelvic endometrial deposits may be found on the ovaries, peritoneum, uterosacral ligaments, pouch of Douglas, and retrovaginal septum, rarer extra-pelvic endometrial deposits have been found in the abdominal wall, the urinary and gastrointestinal tract, the thorax and the nasal mucosa (Machairiotis et al, 2013). The ectopic tissue responds to ovarian stimulation and proliferates and sheds in a similar way to the endometrium that is in the correct place (the eutopic endometrium). This subsequently results in internal bleeding, inflammation, fibrosis, and adhesion formation.

Figure 1. Diagram of a woman with endometriosis showing the attachment of fragments (blue) of the endometrium in the pelvic cavity. The fragments have adhered to the fallopian tube (pink, upper left), the ovary (white, upper centre), the uterus wall (pink, upper centre), the bladder (centre) and the rectum (down right).

Figure 1. Diagram of a woman with endometriosis showing the attachment of fragments (blue) of the endometrium in the pelvic cavity. The fragments have adhered to the fallopian tube (pink, upper left), the ovary (white, upper centre), the uterus wall (pink, upper centre), the bladder (centre) and the rectum (down right).

Prevalence

The exact prevalence of endometriosis is unknown, due to the differences in presentation and the reported delay in diagnosis. However, endometriosis is estimated to affect around 1.5 million women in the UK, and is the second most common gynaecological condition after fibroids (NICE, 2017a). The financial burden of endometriosis on the healthcare system is reported to be substantial, and similar to other chronic diseases such as diabetes, Crohn's disease and rheumatoid arthritis (Simoens et al, 2012).

Aetiology

The cause of endometriosis is uncertain and contested and there is no definite cure (World Endometriosis Society and the World Endometriosis Research Foundation, 2012). Several theories exist, including: retrograde menstruation (the back flow of menstrual fluid along the fallopian tubes into the peritoneal cavity), genetics, immune dysfunction or environmental causes. The current consensus is that endometriosis has a multifactorial aetiology, involving a combination of genetic, immunological and endocrinological factors (Hickey et al, 2014).

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms of endometriosis vary in their presentation and severity, with often poor correlation between the severity of symptoms and the extent of disease (Kennedy and Koninckx, 2012). While some women experience painful symptoms and/or infertility, other women may be asymptomatic and their endometriosis is found incidentally. Consequently, severe disease may remain undiagnosed. Table 1 outlines a range of possible symptoms.

Table 1. Range of endometriosis symptoms

|

NICE (2018: 7) suggests that endometriosis should be suspected in women, including young women under 17 years of age in whom symptoms may often be overlooked, with one or more of the following signs:

- Chronic pelvic pain

- Period-related pain that impacts on daily activities and quality of life

- Deep pain during or after sexual intercourse

- Period-related or cyclical gastrointestinal symptoms such as painful bowel movements with periods

- Period-related or cyclical urinary symptoms, such as pain on micturition or haematuria

- Infertility combined with one or more of the other listed symptoms.

The journey to an endometriosis diagnosis is often long and complicated by women delaying seeking help—as they perceive their painful periods to be normal—and misdiagnoses by health professionals (Hudelist et al, 2012). The timeframe from first symptom onset to surgical diagnosis can take an average of 5–8.9 years (Culley et al, 2013). This delay in diagnosis can result in further disease progression and adhesion formation that may compromise the woman's fertility (Agarwal et al, 2019). A key aim of the NICE guidance (2017a) is to increase women's and health professionals' awareness of the condition to address the diagnostic delay and promote timely referral to more specialist services to maximise the best outcomes for women with endometriosis.

Impact on women's lives

Given the uncertain and enigmatic nature of the condition and the reported delays to diagnosis, endometriosis can impact on women's lives across a wide range of domains, including work and social life, family life and intimate relationships (Culley et al, 2013), and quality of life more generally (Friedl et al, 2015). The NICE guidance (2017a: 6) has a clear message that health professionals must ‘be aware that endometriosis can be a long-term condition, and can have significant physical, sexual, psychological and social impact. Women may have complex needs and require long-term support’.

In addition to the physical implications of the condition (see Table 1), endometriosis can negatively impact on women's psychological well-being. Evidence suggests that women with endometriosis present with high levels of depression and anxiety, which in turn can influence their perceptions of the physical pain associated with the condition (Laganà et al, 2015). Endometriosis may also have negative effects on women's sexual functioning; chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia, female sexual dysfunction and associated infertility (or concerns about potential infertility) may disrupt couples' intimate relationships (Pluchino et al, 2016; Culley et al, 2017).

Endometriosis is also associated with infertility via multiple mechanisms ranging from hormonal dysfunction; oocyte dysfunction; dysfunction of the secretory phase of the menstrual cycle; inflammation, which interferes with sperm–oocyte interaction; low embryo quality; reduced implantation rate; and decreased ovarian reserve (Tanbo and Fedorcsak, 2017).

Investigations and diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on the woman's history, signs and symptoms, corroborated by a physical examination and imaging techniques, and finally proven by histological examination of specimens collected during laparoscopy, which is considered the gold standard for diagnosis of endometriosis (ESHRE, 2013). Women with suspected endometriosis should be offered a pelvic and abdominal examination to identify any masses, reduced organ mobility or enlargement, or any nodules or endometriotic lesions (NICE, 2018: 5). Women should also be advised to keep a pain and symptoms diary to aid discussions (NICE, 2017a: 7). If there is suspected endometriosis-related subfertility, there should be multidisciplinary team involvement with input from a fertility specialist (NICE, 2017a: 13).

A detailed patient history should be taken with specific enquiry into:

- Gynaecological and obstetric history

- Menstrual history including recurrent painful periods and severe dysmenorrhea—elicit cyclical nature of pain, severity and/or association with other symptoms like pelvic pain

- Painful intercourse such as deep dyspareunia

- Chronic lower abdominal, pelvic and lower back pain. Constant aching dragging pain may be exacerbated by menses due to stretching of tissues, and local production of prostaglandins in the ectopic endometrial implants

- Infertility

- Painful micturition manifesting as cystitis or cyclical haematuria (infrequent presentation is obstructive uropathy)

- Dyschezia due to gastrointestinal tract endometriosis (cyclical rectal bleeding may occur due to endometriotic bowel disease)

- Family history of endometriosis

- Other cyclical symptoms related to endometriosis outside the pelvis.

Examination

- Abdominal examination generally does not show any pathology but should be undertaken to exclude any masses and/or tenderness, especially if vaginal examination is not appropriate (NICE, 2017a)

- Pelvic bimanual examination to assess for masses, organ mobility, enlargement and nodules (NICE, 2017a)

- Rarely disease may be visible in the vagina or cervix, such as blueberry lesions (blue–red or blue–black lesions/area on the cervix).

Investigations

- Ultrasound: may lack resolution to visualise superficial peritoneal and ovarian implants and adhesions. However, a transvaginal ultrasound scan (TVS) can detect ovarian endometriomas, solid nodules within the posterior vaginal wall and/or bladder nodules. A negative ultrasound (or MRI) does not exclude endometriosis, especially if there is a clinical suspicion (NICE, 2017a)

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): although not a first-line imaging method (NICE, 2017a), it may be used in specialist endometriosis centres when planning surgery

- Laparoscopy: it can sometimes be difficult to delineate the endometriotic lesions from fibromuscular tissue on laparoscopy. The use of laparoscopy for diagnosis of endometriosis is important, but it is an invasive procedure. Biopsy of at least one lesion is advisable at laparoscopy. Laparoscopy can be diagnostic but can also be operative to treat any endometriosis found

- Do not use serum marker CA 125 (NICE, 2017a)

- Do not use staging systems. Offer treatment according to the woman's symptoms and preferences, but if a laparoscopy is performed, a detailed description of the appearance and site of endometriosis should be recorded (NICE, 2017a).

Treatment options

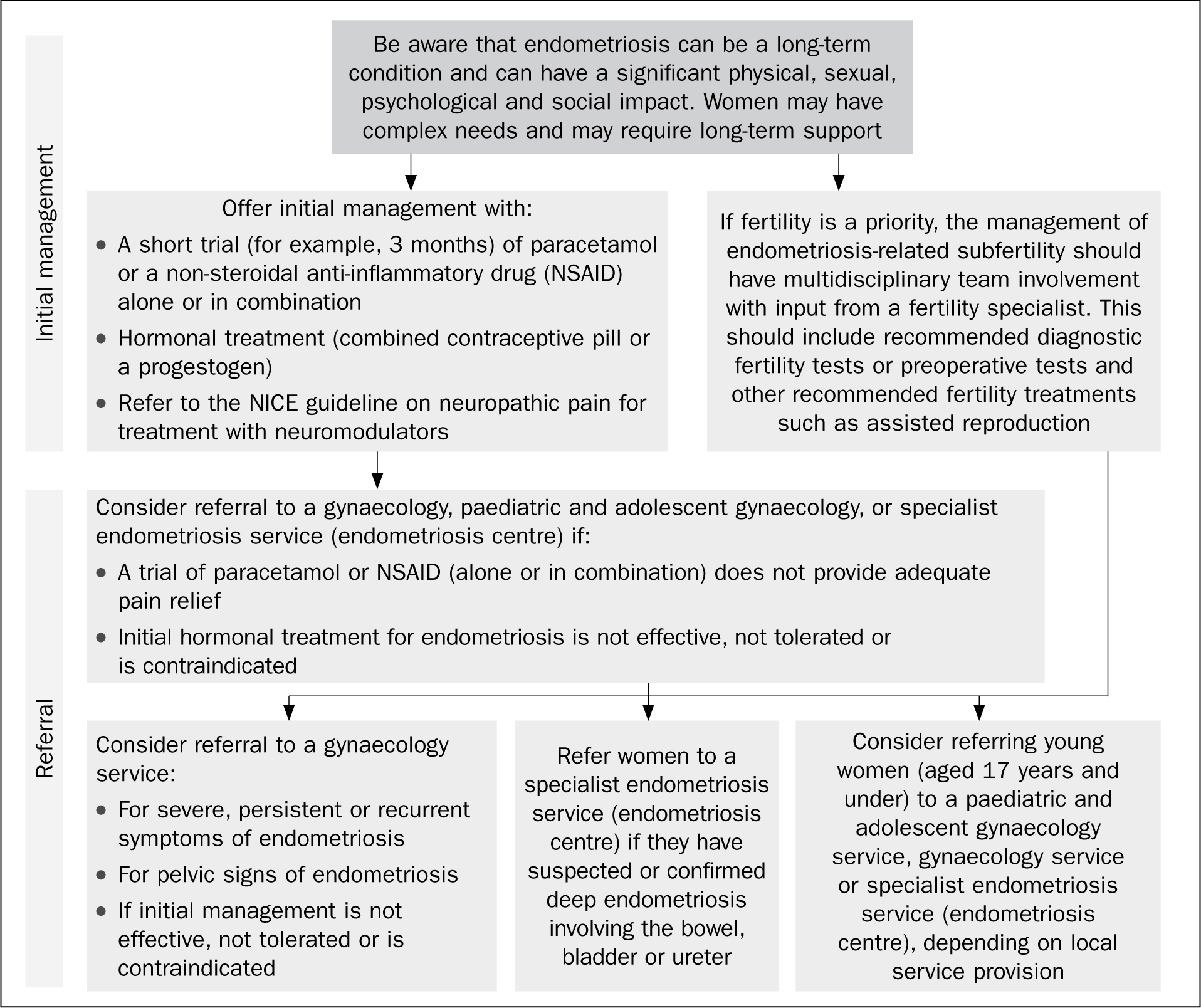

As there is no cure for endometriosis, patients' treatment pathways are aimed at managing the disease, and focus on symptom management. Referral to secondary care may need to be considered at the earliest opportunity (see Figure 2). Treatment options can be hormonal, non-hormonal or surgical, and they have varying rates of success (ESHRE, 2013). If women are trying to conceive then non-hormonal treatment is the only option open to them, other than surgery (NICE, 2017a). Symptom recurrence is common following any medical and surgical treatment of endometriosis, as treatment suspends the endometriosis but does not cure it. Treatment options may also have potential side-effects, which may impact negatively on women's quality of life.

Figure 2. National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE, 2017a) algorithm outlining referral pathway from primary to secondary care. NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Figure 2. National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE, 2017a) algorithm outlining referral pathway from primary to secondary care. NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Medical treatment of endometriosis

Medical treatments can be used in combination with surgical interventions and can be hormonal or for pain relief.

Non-hormonal treatment

- Analgesics: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) work by blocking the production of prostaglandins in the body. Prostaglandins are naturally occurring in response to injury or disease, and cause pain and inflammation. In women, they also make the uterus contract during a period, and it may be that women with endometriosis have more prostaglandins and therefore more pain. As with most analgesia, they are more effective if taken before the onset of pain, such as when the period is due to start. Women can also be advised to use other analgesia at the same time, such as paracetamol or codeine-based analgesia. If a woman in primary care has not gained any benefit from a 3-month trial of paracetamol and/or NSAIDs, then consider referral (NICE, 2017a) (see Figure 2)

- Pain modifiers: some women may not want, or be able, to take hormones and may be referred to pain clinics for more specialised medications such as pain modifiers, which work by altering the body's perception of pain. These drugs are not normally first-line treatments, but can be used by pain specialists if needed. This group of drugs include amitriptyline, which can be prescribed for depression but can also help with nerve pain.

Hormonal treatment

Hormonal treatments can be offered to women who are diagnosed with, or suspected of having, endometriosis. However, women may have concerns about the side-effects of hormones. NICE (2017b) have produced a decision aid to help women decide if/what hormone treatment is right for them. NICE (2017a: 11) suggest that hormonal treatment can reduce pain and has no permanent negative effect on subsequent fertility. If a 3-month trial has not been effective, then referral to secondary care is indicated. Available hormonal treatments include:

- Combined oral contraceptive pill (COCP): contains a combination of oestrogen and progestogen. It works by suppressing ovulation and therefore menstruation. Due to the effects of the hormones in the COCP, the endometrium and the endometriosis deposits are thinner. The COCP is usually used continuously for women with endometriosis, so there are no breaks and no bleeding. This regime is outside the manufacturer's licence but is supported by the Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare (FSRH, 2019)

- Levonorgestrel-releasing hormone intrauterine system (LNG IUS, eg Mirena): a small plastic T-shaped intrauterine device containing progestogen. An IUS may also be used for contraception. Some women find the Mirena fitting painful. The progestogen slowly releases into the uterus over a period of 5 years, suppressing the growth of the endometrium and endometrial deposits so they become thin and inactive. The Mirena does not always prevent ovulation, but as the progestogen acts locally, it reduces endometriosis-linked pain (dysmenorrhoea, dyspareunia) associated with extensive pelvic and rectovaginal endometriosis

- Oral progestogens (eg Provera): thought to relieve endometriosis symptoms by suppressing the growth of endometriosis deposits and reducing endometriosis-induced inflammation. During treatment a woman will stop ovulating and menstruating, although this treatment regime is not licensed for contraception. Some women experience pre-menstrual syndrome like side-effects

- Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues: modified versions of the naturally occurring GnRH, which controls the menstrual cycle. By switching off these hormones the woman enters a temporary menopausal state, resulting in menstruation ceasing and the endometriosis becoming inactive and reduced. It is often recommended that women are prescribed hormonal ‘add-back’ therapy or hormone replacement therapy (HRT) to reduce and/or prevent the side-effects of these drugs (eg leuprorelin (Prostap); goserelin (Zoladex)). These are normally prescribed within a gynaecology clinic and generally restricted to 6 months of use because of the risk of bone demineralisation in some women after this time period. The ‘adding back’ of oestrogen and progestogen can protect against bone mineral loss during and up to 6 months after treatment.

‘Practice nurses need to be aware of the range of endometriosis symptoms, in order to accelerate earlier diagnosis and timely referral to specialist services.’

Surgical management of endometriosis

Surgery can be dependent on the extent of the disease and the woman's main priorities with respect to pain and fertility. Types of surgery include:

Laparoscopic ablation/excision of endometriosis lesions

This is undertaken by laser or diathermy and is effective for a large number of women. Both NICE (2017a) and the British Society for Gynaecology Endoscopy (BSGE) recommend excision be considered rather than ablation for endometriomas (Byrne et al, 2018). Deep endometriosis needs referral to a BSGE specialist centre. Hormonal treatment can also be considered post-operatively if the woman is not trying to conceive (NICE, 2017a).

Radical surgery

Total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH) and bilateral salpingo-oopherectomy (BSO) removes the entire lesions in severe and deeply infiltrating endometriosis, resulting in improved pain relief. Women should be told that hysterectomy will be combined with excision of all visible endometriotic lesions, and informed of the risks, benefits and the likely outcome (NICE, 2017a). Women may still experience pain, as there can be deposits which can be reactivated with hormones; research suggests that 15% of women still complain of chronic pelvic pain after a TAH (Vercellini et al, 2009). Cases of endometriosis involving the bladder and bowel, or close to the bowel, should be managed by multidisciplinary teams in BSGE specialist endometriosis centres.

Complementary therapy/other interventions

NICE (2017a) advises that the available evidence does not support the use of traditional Chinese medicine or other herbal medicines or supplements for treating endometriosis. However, some women do find relief from the following interventions:

- High frequency transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS)

- Acupuncture

- Vitamin B1 and magnesium supplements may help to relieve dysmenorrhoea (Proctor and Murphy, 2001)

- Dietary adjustments

- Physiotherapy: physiotherapists can develop a programme of exercise and relaxation techniques designed to help strengthen pelvic floor muscles, reduce pain, and manage stress and anxiety. After surgery, rehabilitation in the form of gentle exercises, yoga or Pilates can help the body get back into shape by strengthening compromised abdominal and back muscles.

Useful resources

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: https://www.nice.org.uk

- Endometriosis UK: https://www.endometriosis-uk.org

- British Society for Gynaecological Endoscopy: https://www.bsge.org.uk

- Endometriosis.org

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists: https://www.rcog.org.uk

- European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology: https://www.eshre.eu

- The World Endometriosis Society: https://endometriosis.ca

Support groups

NICE (2017a) suggests that women should be given information on endometriosis and informed of how to access local and national support groups, including online forums or virtual support groups. It is essential that nurses are aware of the range of resources available, and how to signpost women to these, as long-term peer support can be invaluable for women with endometriosis.

Role of the nurse

Practice nurses may come into contact with women with endometriosis in a variety of ways: during cervical screening, contraception, and when reviewing other conditions, for example. An awareness of endometriosis, and an understanding of the current evidence and NICE best practice guidance and decision aids, is important in supporting nurses to provide women with appropriate individualised care. Nurses can be instrumental in recognising the symptoms of endometriosis, and understanding the impact of this diagnosis on women's daily lives and their relationships. Endometriosis can affect women on a physical, psychological and social level, so a holistic and sensitive approach to care is imperative in supporting women to cope with this condition. Nurses can play a pivotal role in facilitating diagnosis, providing patient education and psychological support, to empower women to negotiate their own needs and treatment preferences.

Nurses' clinical practice can be guided by the Royal College of Nursing's (RCN, 2018) factsheet, designed to help nurses recognise the symptoms of endometriosis and aid early referral, and the NICE guidance, decision aids and quality standards to ensure the delivery of high-quality care.

What can the practice nurse do?

There are several important things that practice nurses can do to help women with endometriosis:

- Take a detailed history

- Use the NICE guidance and the RCN endometriosis checklist to help recognise and focus on specific signs and symptoms of endometriosis

- Listen to the woman's account of how her activities of daily living are affected

- Allow time for the woman to disclose sensitive information such as the impact on her sexual relationship or fertility concerns, for example

- Empower women by educating them about endometriosis

- Explore the range of treatments and their implications

- Discuss health promotion interventions

- Signpost to relevant support services

- Recognise the need for onward referral to multi-disciplinary team members, gynaecology endometriosis services and clinical nurse specialist teams

- Audit care against the quality standards (see Box 1).

Box 1.NICE (2018) quality standards

- Statement 1: Women presenting with suspected endometriosis have an abdominal and, if appropriate, pelvic examination

- Statement 2: Women are referred to gynaecology services if initial hormone treatment for endometriosis is not effective, not tolerated or contraindicated

- Statement 3: Women with suspected or confirmed deep endometriosis involving bowel, bladder or ureter are referred to a specialist endometriosis centre

Conclusion

Endometriosis is a long-term chronic condition affecting women throughout their reproductive lives (and sometimes beyond), which can have a significant physical, sexual, psychological and social impact (NICE, 2017a). This condition is often misunderstood and misdiagnosed leading to reported lengthy delays in achieving a diagnosis, which can affect women's quality of life and result in disease progression (NICE, 2017a). Practice nurses need to be aware of the range of endometriosis symptoms, in order to accelerate earlier diagnosis and timely referral to specialist services. This article highlights the important educational role of nurses in raising awareness of this condition and providing a holistic individualised approach for women with endometriosis to support their overall quality of life.

KEY POINTS:

- Endometriosis is estimated to affect between 2 and 10% of women in the general population, but up to 50% of women with infertility

- This condition can impact on women's lives across a wide range of domains, including work and social life, family life and intimate relationships

- Endometriosis is often misunderstood and misdiagnosed, leading to reported delays in diagnosis of 5–8.9 years

- Nurses play a pivotal role in facilitating diagnosis, providing patient education and psychological support, to empower women to negotiate their own needs and treatment preferences

CPD reflective practice:

- After reading this article, reflect on ways in which your practice could be improved

- What education resources are displayed in your clinical area to raise awareness of endometriosis?

- How do you assess women's symptoms as possibly indicative of endometriosis?

- What range of support resources could you signpost women to?