Emergency contraception (EC) is defined as a contraceptive method that is administered after sexual intercourse but has its effects before implantation (considered to occur no earlier than five days after ovulation).

Though EC is no substitute for effective regular contraception, EC can provide a valuable option for women who are at risk of pregnancy following a problem with their usual contraceptive method or unprotected sexual intercourse (UPSI). There are three methods of EC available in the UK. This article describes the features of each and which is most appropriate in any given clinical situation.

What are the side effects of emergency contraception?

A systemic review of safety data (Jatlaoui et al, 2015) for adverse events relating to use of EC in healthy women concludes that such events are rare.

Headache, nausea and dysmenorrhea have been reported in about 10% of users of Ulipristal Acetate Ella (UPA-EC)and Levonorgestrel (LNG-EC). It is important to advise the woman that if she vomits within three hours of taking oral EC, a repeat dose is required. After taking oral EC, menses can be delayed. However, if the period is delayed by more than seven days, a pregnancy test should be advised.

What about the risk of sexually transmitted infections in emergency insertions of copper IUD?

A sexual history and chlamydia screening should be carried out on all patients attending for Copper IUD (CU-IUD). CU-IUD insertion risks causing or exacerbating pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) so STI risk should be judged from the history. If the woman is not in a high-risk group (monogamous plus no recent partner change and can be contacted if the sexually transmitted infection (STI) screen gives a positive results) routine antibiotic prophylaxis is not required.

If a woman has known symptomatic chlamydia infection or current gonorrhoea infection then ideally antibiotic treatment should be completed prior to insertion of a CU-IUD. However, the Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare (FSRH) in its statement on antibiotic cover for emergency CU-IUD 2019 states:

‘If, immediate insertion of a CU-IUD for emergency contraception is required, IUD insertion with antibiotic cover could be considered. Clinical judgment based on the nature and severity of symptoms and discussion with the woman is required.’

If the woman has asymptomatic chlamydia infection, then insertion of a CU-IUD for EC may be considered after discussion with the woman regarding risk and benefits. Treatment with appropriate antibiotics should be given at the time of insertion. Prophylactic antibiotics should be considered in a woman who is considered at risk of an STI but whose results are unavailable, especially if she cannot easily be contacted with the result. Post-insertion, inform the patinet about symptoms that should alert them to infection, such as pelvic pain, dyspareunia, abnormal or offensive vaginal discharge, and where to seek help.

What about breast cancer?

UPA-EC or LNG-EC may be used by women at risk of breast cancer or breast cancer recurrence who decline emergency placement of CU-IUD.

The prognosis for women with breast cancer may affected by hormonal contraception. However, LNG and UPA are UKMEC 2 (United Kingdom Medical Eligibility Criteria for contraception, 2016), because their benefits outweigh the risks and an adverse effect is exceptionally unlikely with such short term exposure. The best option is still CU-IUD because of its increased efficacy (FSRH, 2016).

If emergency contraception fails, what are the risks?

There is no evidence of an adverse pregnancy outcome or foetal abnormality if pregnancy occurs despite use of LNG-EC or UPA-EC. Use of EC does not affect a woman's long term fertility.

Table 1. Methods of emergency contraception

| Copper IUD | Ulipristal Acetate Ella One®30 mg stat | Levonorgestrel Levonelle 1500® 1.5 mg stat | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Timing |

|

|

|

| Mode of action |

|

|

|

| Efficacy |

|

|

|

| Contraindication |

|

|

|

| Breast feeding |

|

|

|

| Drug interactions (FSRH Drug interactions with hormonal |

|

|

|

| Effect of weight/BMI on effectiveness |

|

|

|

Ectopic pregnancy is not thought to be any more common than in women who have not taken EC (Cheng et al, 2012). Nevertheless, women should be warned to seek advice should they experience pelvic pain. In the unusual event of a continuing pregnancy following IUD insertion, an ultrasound scan should be arranged and the IUD removed.

Some examples of contraceptive failure that would indicate the need for EC

- Spilt/slipped condom

- Complete/partial expulsion or removal of IUC (intrauterine contraception) at midcycle

- IUC threads missing and location of IUC unknown

- Misplaced diaphragm

- UPSI more than 14 weeks from previous DMPA (depot medroxyprogesterone acetate) injection or within seven days after late injection

- UPSI after the contraceptive implant has expired

- UPSI during and for 28 days after use of liver enzyme inducers in those relying on CHC (combined hormonal contraception), POP (progestogen only pill) or contraceptive implant

- UPSI at any time from the first missed POP until POP has been correctly taken for at least 48 hours

- Significant prolongation of hormone free interval (HFI) in CHC user ie by nine days or more. For example, UPSI during HFI and method restarted late by two days or more; patch detached, ring removed or pills muddled during week one and no extra precautions used.

What are the most important areas to cover in a consultation for emergency contraception?

- Take a menstrual and coital history to see if treatment is necessary. In general, better to treat than to with hold

- Take a sexual history, remember ‘germs as well as sperms'. Offer an STI screen

- Discuss all EC methods available, their mode of action, efficacy, risks and side effects. If available use a good leaflet, or text link to Family Planning Association website

- Offer everyone CU-IUD (unless contraindicated) as this is the most effective method. Document that you have offered this and the patient's response

- If you are unable to offer CU-IUD, provide oral emergency contraception (in case the IUD cannot be fitted or patient changes her mind) and make necessary referral to a fitter. Ensure you have a clear referral pathways

- Explore her attitudes to possible failure and continuance of pregnancy

- Advise importance of a pregnancy test at least three weeks after the last episode of UPSI. Ideally, an early morning sample

- Advise woman to seek advice if she has pelvic pain or irregular bleeding or malodourous vaginal discharge

- Provide contact details should vomiting occur within three hours of taking oral EC

- Discuss quick starting contraception.

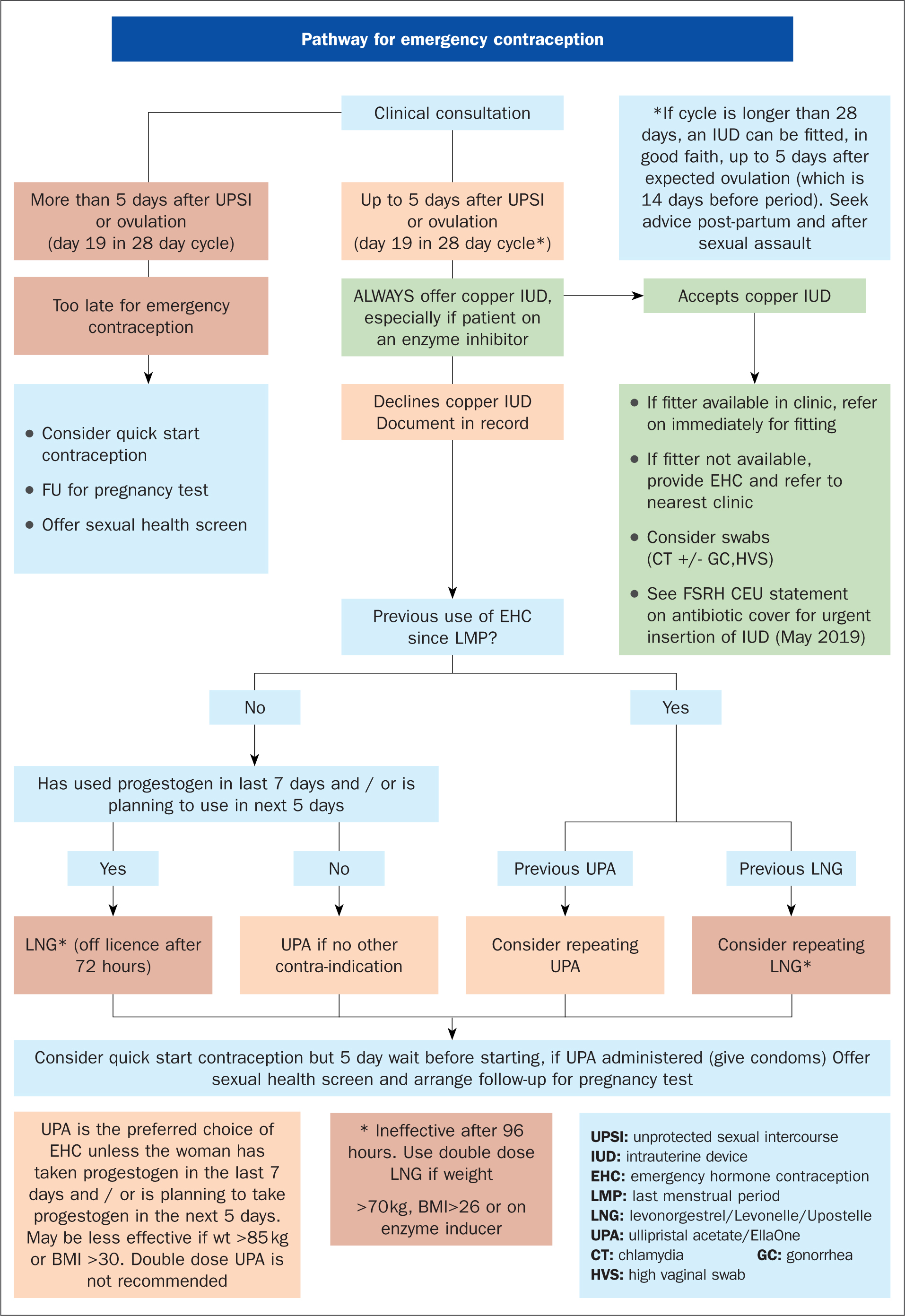

Figure 1. Pathway for emergency contraception (Sexual Health Dorset)

Figure 1. Pathway for emergency contraception (Sexual Health Dorset)

Examples of some questions to ask when taking a history

- When was your last menstrual period?

- Was the last period unusual in anyway (eg later, lighter, shorter than normal)?

- What is your shortest and longest cycle length?

- Which day(s) in the cycle did UPSI occurred?

- How many hours since first UPSI?

- What is your current method of contraception?

- Have you used EC within this cycle?

- If you have used EC in the past, did you experience any problems?

- How long have you been with your partner?

- When did you last have sex with anyone else?

Can hormonal contraception be given more than once in a given cycle?

Yes, because clinically we cannot be certain when ovulation occurs. Halpern et al (2014) suggests that repeated use of either LNG-EC or UPA-EC will not induce abortion if the woman is already pregnant and hence either can be given in the same cycle. However, because circulating progestogen appears to reduce the effectiveness of UPA-EC, LNG-EC is recommended if LNG-EC or any progestogen has been taken within the previous seven days (Lesam et al, 2016). Similarly, with seven days following UPA-EC, repeat UPA-EC and not LNG-EC.

A consultation for repeat emergency contraception may be an opportunity to discuss more effective on going contraception or consider CU-IUD.

Are there any occasions when treatment is not necessary?

- UPSI before day 21 after childbirth, for all women, whatever the chosen method of infant feeding. However, if the woman is fully breast feeding, has amenorrhea and baby is under six months old, then EC is not required (Diaz, 1988)

- UPSI before day five after abortion, miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy or uterine evacuation for gestational trophoblastic disease

- The risks of treatment are low and cycles can be variable so better to treat whatever the day of the cycle

- Patient is aged over 55 years.

Should perimenopausal women be offered EC?

Yes, because despite erratic menses they may still ovulate. Hormone replacement therapy is not contraceptive and could reduce the effectiveness of UPA-EC. For more information see (FSRH). Contraception for Women Aged Over 40. 2010.

Will LNG-EC work if given more than 72 hours after UPSI?

Yes, but not very well. Evidence suggests that LNG-EC is ineffective if taken more than 96 hours after UPSI (Noe 2011)

What should be advised regarding future contraception?

CU-IUD offers immediate on going contraception for its licensed duration. Oral EC methods do not provide ongoing contraception. If ovulation occurs later in the same cycle and UPSI takes place, there is a pregnancy risk. After taking LNG-EC women should be advised to start suitable hormonal contraception immediately and use condoms until that method becomes effective.

Women should be advised to wait five days after taking UPA-EC before starting hormonal contraception. For example, use condoms for a minimum of 48 hours after POP has been immediately restarted and carry out a pregnancy test 21 days later to exclude pregnancy. This is because Brache 2015 has shown that starting desogestrel POP immediately after reduces the ability of UPA-EC to delay ovulation. Studies have not be carried out using other contraceptives, but extrapolating from this evidence Faculty (2017) advises that no hormonal contraception should be used for five days after UPA-EC has been given.

FSRH advise that DMPA and the contraceptive implant can be quick started after LNG-EC or five days after UPA-EC has been given. However, DMPA is not easy to reverse so some women may prefer to defer DMPA until a follow up pregnancy test 21days after UPSI to confirm that the woman is not pregant. LNG-IUS should not be inserted, unless pregnancy can be reasonably excluded.

Women using fertility awareness methods, who choose hormonal EC, should avoid intercourse throughout the first cycle post EC and then restrict intercourse to the late infertile time until regular ovulatory cycles are re-established (Knight, 2017).

Can hormonal EC be supplied in advance of need?

This may be considered in women who rely on barrier contraception or are travelling abroad. Systemic review (Rodriguez, 2013) concluded that, compared with conventional provision, advance provision did not reduce pregnancy rates. If supplied in advance, EC is taken sooner, and does not lead to increased frequency of UPSI or increased risk of STI. However, many women in the trials did not use EC after UPSI despite having a supply.

Useful resources

www.fsrh.org

www.fpa.org.uk

www.fertilityuk.org

Key Points

- Discuss ALL EC methods available

- Offer everyone copper IUD (unless contraindicated). Document that you have offered this and the patient's response

- Discuss and provide ongoing contraception

- Take a sexual history and consider referral to STI screening services

- Know pathway to IUD fitter