Osteoporosis can be seen as the ‘silent epidemic’. In England and Wales, around 180,000 of the fractures presenting each year are the result of osteoporosis. More than one in three women and one in five men will sustain one or more osteoporotic fractures in their lifetime (NICE 2021).

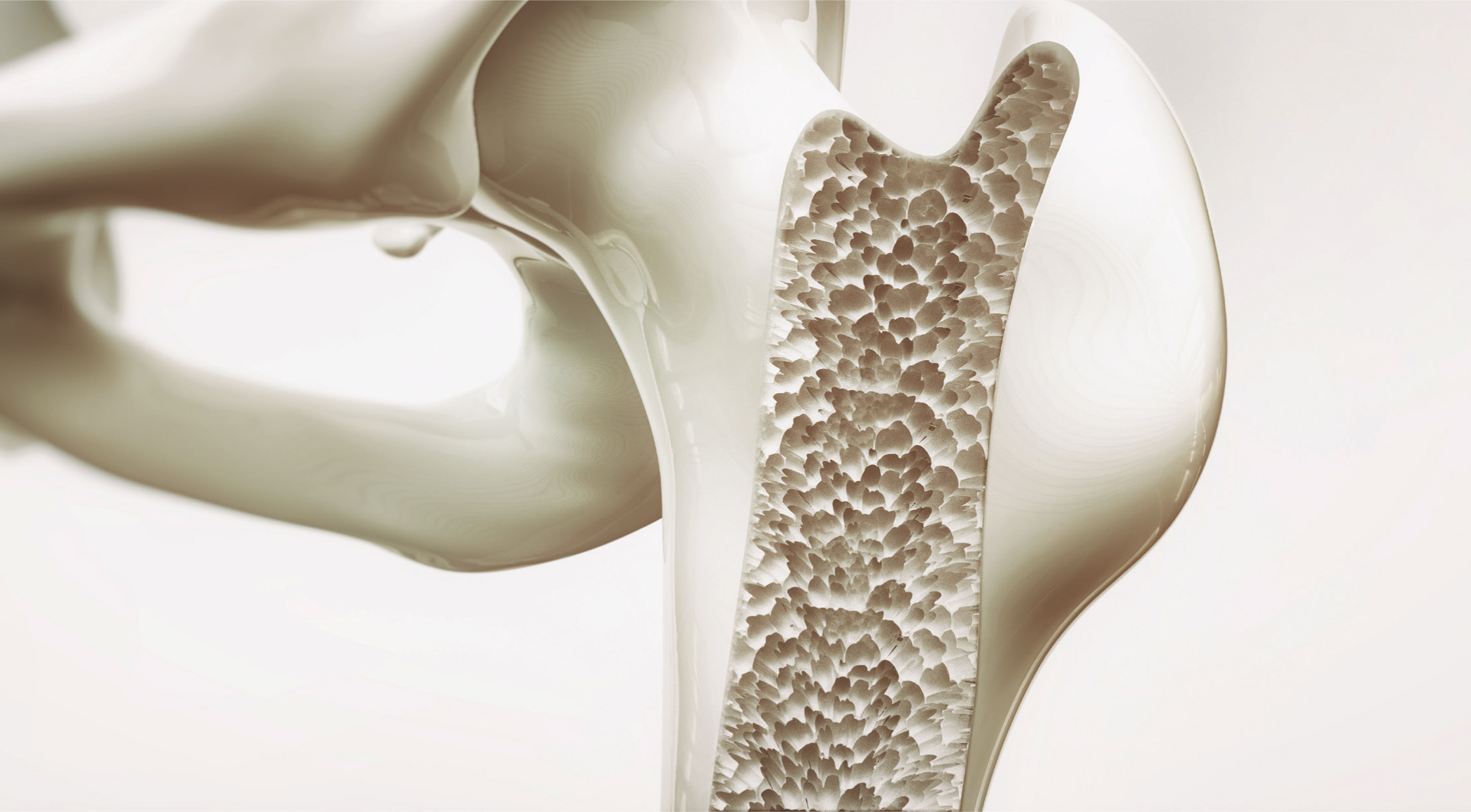

Osteoporosis is a state in which bone is fully mineralised, but its structure is abnormally porous, and its strength is less normal for a person of that age. (Apley et al, 1993). This weakens the bones and increases the risks of falls leading to fractures. Osteoporosis is the result of bones losing both protein (collagen) which helps bones flex slightly under strain and calcium which makes them strong. Women at the menopause and the next 10 years lose bone at an accelerated rate – 3% per year compared to 0.3% during the preceding decade. This happens when the ovaries stop making the hormone oestrogen or it can be seen as the ageing process.

It is important to look at the impact osteoporosis has on women's health; what the risk factors are; and how to improve care in the future.

Osteoporosis can have a major impact on women's health and family life. Where many feel menopause is overrated as a negative psychological event in a woman's life, middle age may coincide with life experiences such as:

Psychological problems can lead to depression, violence and abuse. Some women can have injuries from falls resulting in fractures, there can be side effects from medication or treatment. Economic factors can also play an important part in getting access to services.

People on low incomes often eat fewer fruit and vegetables and have limited cooking and storage facilities. Knowledge about food and health vary in social classes.

Women tend to use preventative services more than men if accessible. However, current demands on health and social care is high and not always available when needed.

Women's role and responsibilities can be stressful. Not only do they provide care and support for family members, partners and employers they may have concerns regarding their own health and well-being: their appearance, sexuality, body image and socialisation. Blunt (2025) believes various life circumstances have been found to threaten a woman's psychological or emotional wellbeing and which can have a negative effect on their mental health.

What are the risk factors for osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures?

Osteoporosis is initiated by an imbalance between bone resorption and formation. Diet, lifestyle factors and genetic factors can play an important part. Sommer et al (2012) demonstrated results from a study which suggested low to moderate alcohol intake may exert protective effects on bone health in elderly women but should be counselled regularly about cigarette smoking, alcohol intake and oestrogen status.

Jenny Kiratli et al (1996) refer to the main risk factors as being:

McPherson (1994) states the association of smoking and alcohol use, with abnormal menstrual patterns. Smokers are more likely to experience the menopause about two years earlier than non-smokers.

However, race, sex, hereditary, hormones and diet all influence bone density. Excessive exercise, anorexia nervosa or endometriosis drugs can lead to osteoporosis and prolonged use of corticosteroid drug treatment or hysterectomy with removal of ovaries. Although bilateral oophorectomy in middle age was previously regarded as a wise form of preventative surgery and ovaries have no endocrine function after the menopause McPherson (1994) studies show ovaries do not cease to be hormone producing organs at the end of the reproductive life. Removal, even in post-menopausal women will deprive them of oestrogen and androgens and others which may have important implications for sexuality.

Although the reasons are uncertain, osteoporosis is much less common in Black men and women than white people. It is argued that possible lifestyle differences or genetic factors could be the reason.

The prevalence of osteoporosis is very high in industrialised countries among post-menopausal women. Environmental factors and social class play a major role. Schutte et al (2008) highlight environmental exposure to cadmium, which decreases bone density indirectly through hypercalciuria resulting from renal tubular dysfunction. The study measured 24-hour urinary cadmium and blood cadmium and found exposure increases bone resorption. Cadmium pollutions are past and present emissions from industries, waste incineration, use of fertilisers and sewage sludge, burning fossil fuels and inhalation of tobacco smoke.

McPherson (1994) refers to factors such as:

The declining skeletal health of westernised women, environmental determinants of fracture risks and reduced public health measures are all potential risks.

How can risks be reduced and why?

Osteoporosis places an enormous financial burden on the NHS and society as well as pain and disability for the individual which could result in death. Bennett (1995) states an estimated £750 million was spent in 1994 on fracture management and social care.

Park et el (2021) state that fractures caused by osteoporosis most often occur in the spine. Spinal, or vertebral compression, fractures occur an estimated 1.5 million times each year in the USA. They are almost twice as common as other fractures typically linked to osteoporosis, such as broken hips and wrists.

Baji et al (2023) highlight a study of organisational factors associated with hospital costs and patient mortality in the 365 days following hip fractures in England and Wales. (REDUCE) a record linkage cohort study discovered the cost patients spent in hospital was around 21 days incurring costs of £14,642 per patient ranging from £10,867 to £23,188 between hospitals.

According to the Royal Osteoporosis Society (2022), over 500,000 fractures occur each year in the UK, costing over £4.5billion. Hip fractures account for £2billion of this cost (including £1.1 billion for social care).

All require after care. Fractures are painful, may need reduction and 4-6 weeks in plaster. Many are hospitalised causing concern to families and dependants. Loss of income will affect all the family's wellbeing. Support and equipment will be needed on discharge. Complications can arise from operations: rehabilitation from hip replacements can lead to pneumonia, pressure sores, urinary and pin site infections. Current waiting times for operations vary. It can be a long time to suffer pain and disability, so to prevent and reduce the risks are essential. Where screening appeared to be an inappropriate use of resources because of bone density poorly selected for women at risk, studies have shown selective screening, particularly women who have recently passed through the menopause, will aid the making of a genuine, therapeutic decision.

Khaw (1992) believes bone loss differs considerably between individuals particularly during late post-menopausal women. However, Lindo (2013) believes 85% of bone mass is inheritable, genetic polymorphisms explain only a small portion of variations in bone mass in healthy individuals. Gender. calcium intake, physical activity, obesity and time of puberty must be considered.

Jenny Kiratli et al (1996) refer to the recently developed scans have made it possible to measure bone density using lower doses of radiation than other methods – dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA). However, Nelson (1999) says what is referred to bone mass can refer to a variety of measurements such as bone mineral content and density, and volumetric or true bone density. Ethnic differences in bone mass varied considerably.

There appears to be a relationship between skin thickness and bone mass, with further research estimating skin thickness may be a way to screen women. Jenny Kiratli et al (1996) believe future possibilities could include a urine test to measure loss.

According to Wilson (2013) bone density may be linked to changes on the gene that controls Vitamin D uptake. Nurses play an important role in identifying risks from osteoporosis to recognise what symptoms to look for. This marker could allow doctors to identify and prevent before the menopausal stage – 80% of bone mineral density is under genetic control.

Some women may experience the following:

Doctors may miss the vital warning signs of osteoporosis. Hormone replacement therapy may be prescribed but it does not put strength back into bones nor does it cure osteoporosis. Where it may benefit some of the symptoms, common side effects are fluid retention, nausea, weight gain, irritability, leg cramps and breast tenderness.

According to Green (2015) HRT cannot be described as safe or unsafe. Its effects vary depending on the types of hormone used, the form in which it is given (pills, or patches and gels), and the timing of first use (around menopause, or later). The safety of HRT can also depend on other things, such as body mass index. Over 50's should have routine tests such as blood pressure, weight, breast examination and internal smear test when on HRT blood tests, full medical history is taken and 2 yearly mammogram and 3-5 yearly smears. Well women clinics run by nurses aim to give the correct advice and support and provide health checks. Bell (1996) believes high quality, efficient service run by nurses will meet the needs of women. However, flexibility is vital to ensure attendance, and someone who is sympathetic and has time to answer questions and give advice will help to secure return visits. Demands are increasing and staffing levels need to be considered to allow time for patients. Information must be given to women to make informed decisions. Blunt (2025) highlights the understanding of needs of the patient – physical, spiritual, emotional and environmental – an holistic approach.

Lifestyles need to be considered:

If a patient already has osteoporosis, it is too late to increase bone mass. Adequate pain control is needed such as the correct medication, relaxation techniques, hydrotherapy or acupuncture. Willis (1993) refers to heat pads, pain killers, calcitonin injections, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) and physiotherapy may help pain. Nasal sprays are being developed and calcium and vitamin D supplements are available to sufferers. However, despite treatments being available many must wait long periods to be treated and must travel out of the area. Whatever medication is prescribed patient compliance is vital. Lee et al. (2024) showed the continuation rate of medication was only 33% in one year and 22% in 2 years. Living in a safe environment will reduce risk of falls – slippery floors, trailing flexes, and dark areas. Advice on equipment, footwear, alarm systems and financial benefits will reduce anxiety. Counselling regarding personal and family matters will improve confidence and self-esteem.

Conclusion

By continuing research into osteoporosis treatment can be improved and preventative measures initiated from the cradle to the grave. No longer is it the ‘silent epidemic’ – knowledge will improve standards of care and be introduced to those most vulnerable.

Targets to aim for need to ensure a healthy lifestyle at an early age include:

Practitioners need to recognise the woman's role is complex. Life experiences can lead to psychological and emotional disturbances. A holistic approach to care is vital. Access to services must be improved and time allowed to achieve a diagnosis.

Rachner et al (2011) identified a promising treatment which includes denosumab a monoclonal antibody and ramucirumab (Evenity) which inhibits the protein sclerostin – which plays an important role in bone loss during oestrogen deficiency in postmenopausal osteoporosis. HRT can be given to help women through the menopause to help control the symptoms. The best and safest treatment is bisphosphonates which is often the first choice for osteoporosis treatment. Abaloparatide, an anabolic drug, is currently approved by NICE for post-menopausal woman. More research needs to be done on its potential benefits for men and pre-menopausal women (Royal Osteoporosis Society 2025).

The role of the nurse is to recommend changes for women in the future. This can be done by listening to what the concerns are and ensure that preventative measures are taken before common injuries occur, such as hip fracture, or spinal/wrist fracture, and reduce the risk of anxiety and depression. Warning signs include losing height, changes in posture, shortness of breath and lower back pain. Practice nurses and GPs are well placed to identify these warning signs: fragility fractures, assess patients for osteoporosis, treat them and monitor their adherence to treatment (Rowe 2016). Nurses must be aware that men can be affected by osteoporosis, especially over the age of 65 and older. Numbers of fractures caused by fragile bones in men has increased in recent years.

Recommendations for the future requires early detection by funding research and screening programmes. Education in schools can ensure children are aware of a healthy lifestyle and collaboration between multidisciplinary teams can ensure referral to the appropriate services are available:

Menopause is a natural biological process that marks the end of a woman's reproductive years. To reduce the risks of osteoporosis, a healthy lifestyle from an early age is essential. Treatments will continue to be improved by funding research programmes, but education will be required to ensure compliance to treatment.