Osteoporosis is a condition of weak bones which are more likely to break, after little, or no trauma. It is defined as a ‘progressive systemic skeletal disease characterized by low bone mass and microarchitectural deterioration of bone tissue, with a consequent increase in bone fragility and susceptibility to fracture’. (Peck 1993) Osteoporosis is an asymptomatic condition and so often goes unrecognised until the clinical consequence of fragility fracture occurs. Fragility fractures are fractures that occur from mechanical forces which would not ordinarily result in a fracture – known as low-energy trauma (e.g. a fall from standing height). In the UK, there are approximately 549,000 fragility fractures each year with a cost to the NHS in excess of £4.7 billion per annum. (Borgström, F. et al, 2020) The most common sites for fragility fracture are the hip, pelvis, vertebrae, wrist and humerus. Fragility fractures can be life-altering events with wide ranging biopsychosocial consequences including pain, deformity, disability, loss of confidence and independence.

The risk of fragility fracture can be reduced with a combination of lifestyle modification, falls prevention and osteoporosis treatments. Evidence-based medications recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), such as oral bisphosphonates, reduce fracture risk, are readily available, cost- and clinically-effective and reduce fracture risk by 20-70% depending on fracture site. (NICE 2017) Despite this, there are many patients who may benefit from osteoporosis medicines, for the purpose of reducing their fracture risk, who do not receive it. This discrepancy is known as the ‘osteoporosis treatment gap’ and the reasons for its existence are multifactorial.(Ralston et al 2022)

The role of primary care

The NICE quality standards cover priority areas in the management of osteoporosis in adults. (NICE 2017) The four quality statements will provide a framework for the remainder of this article:

- Adults who have had a fragility fracture or use systemic glucocorticoids or have a history of falls have an assessment of their fracture risk;

- Adults at high risk of fragility fracture are offered drug treatment to reduce fracture risk;

- Adults prescribed drug treatment to reduce fracture risk are asked about adverse effects and adherence to treatment at each medication review;

- Adults having long-term bisphosphonate therapy have a review of the need for continuing treatment.

Identifying people at risk of osteoporosis and fragility fracture

Three risk factors that should trigger a fracture risk assessment are:

Prior fragility fracture (fracture occurring after a fall from standing height or less)

Secondary prevention is important in osteoporosis because the risk of sustaining a second fragility fracture is high. Fracture Liaison Services (FLSs) aim to systematically identify, treat, and refer people over the age of 50 who sustain a fragility fracture. However, FLS provision is patchy and performance is variable, and so primary care nurses still play a vital role in secondary prevention by identifying these patients.

Vertebral fractures are very common in older people but only 30% are diagnosed. This is for several reasons including that there is usually not a preceding fall (80%), back pain is not always present, appropriate imaging may not have been arranged and imaging reports using terms other than ‘fracture’. You should consider whether spinal fractures are present using clinical risk factors such as thoracic kyphosis, height loss (>4cm) or a history of sudden onset back pain. A number of resources in this website give tips on how to diagnose spinal fractures.

Use of systemic glucocorticoids (e.g. prednisolone)

A regular (≥ 3 months) dose of prednisolone ≥5mg daily requires a fracture risk assessment.

History of falls (one or more falls in the last 12 months)

Most non-vertebral fractures occur following a fall and therefore it is recommended that this group receive a fracture risk assessment.

Fracture risk assessment

Fracture risk assessment is performed before requesting a bone density scan (dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry - DXA). This is because bone density only contributes to part of a person's fracture risk. There are several risk factors for fracture which are independent of bone density. We therefore use fracture risk to make decisions about who to treat rather than bone density measurements alone. Bone density measurements can be helpful when choosing or monitoring treatment or to make risk assessment more precise.

In the UK, two fracture risk assessment tools are available and recommended by NICE; FRAX® (https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/FRAX/) and Qfracture® (https://qfracture.org/). Both tools estimate the probability of having a fragility fracture over a ten-year period.

FRAX® can be used to calculate fracture risk for people between the ages of 40 and 90 years. FRAX® can be calculated with or without bone density scan results alongside other relevant risk factors (see table 1). FRAX® computes both the 10-year probability of hip fracture and of major osteoporotic fracture (spine, hip, forearm, humerus) and maps to the National Osteoporosis Guideline Group (NOGG) guidelines (2021) which can be used to inform the need for a DXA scan and treatment.

Table 1. FRAX® Incorporated Risk Factors

| Sex at birth | fragility fractures are twice as common in women |

| Age | the incidence of fragility fracture increases with age |

| Previous fragility fracture | fracture risk is approximately doubled in the presence of previous low trauma fracture |

| Parental history of hip fracture | |

| BMI | (<19kg/m2) |

| Glucocorticoids | (e.g. prednisolone) |

| Current smoking | |

| Alcohol intake of ≥ 3 units per day | |

| Secondary causes of osteoporosis | Such as type 1 diabetes mellitus, hypogonadism and premature menopause (<45 years) |

A DXA measures bone mineral density (BMD). A DXA scan compares the patients BMD to the average BMD of a young healthy adult. This process generates a ‘T-score’; a T-score of -2.5 or below can be used to make a diagnosis of osteoporosis. DXA scans usually measure BMD at the hip and spine. The BMD at the femoral neck is used in a FRAX® assessment.

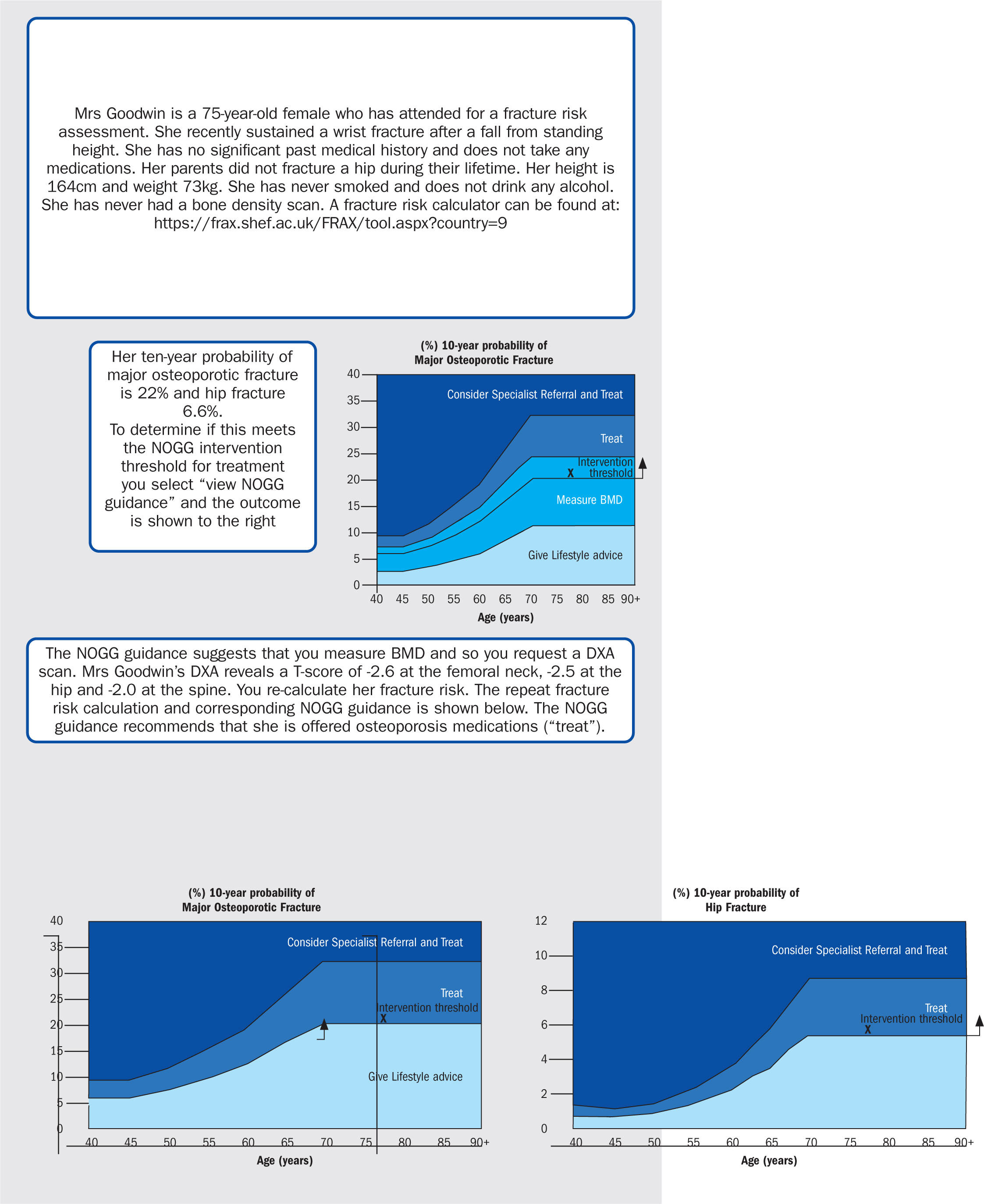

An example, fracture risk calculation using FRAX® is shown in Figure 1.

Recommending osteoporosis treatment

As shown in Figure 1, when using FRAX® the 10-year probability of major osteoporotic and hip fracture is calculated which is mapped to NOGG categories:

Low fracture risk

The patient can be re-assured that their fracture risk is low and given lifestyle advice. Re-assessment of fracture risk is recommended in five years (sooner if the patient sustains a fracture or new risk factors emerge).

Intermediate fracture risk

A DXA scan is recommended. If a DXA is unavailable or not feasible, treatment can be recommended if the risk is above the ‘intervention threshold’ black line.

High fracture risk

Patients should be offered the opportunity to discuss osteoporosis medicines in addition to lifestyle factors with the aim of reducing fracture risk.

Very high fracture risk

Consider referral to secondary care (or advice and guidance) as this group of patients have the most to gain and first-line parenteral treatment may be appropriate. If there is a delay in referral, then oral osteoporosis medications could be started whilst the patient is awaiting review.

Treatments to reduce fracture risk

Non-Pharmacological Treatment and Promotion of bone health

Diet and supplements

Patients should be encouraged to eat a healthy balanced diet that includes adequate protein which is important for maintaining muscle mass in older life. Patients taking osteoporosis medications may benefit from a calcium intake of around 1000mg per day. Ideally, this should come from the diet (e.g. dairy products and leafy green vegetables) but if this is not possible it can be supplemented – 200ml of milk contains around 240mg of calcium.

Most vitamin D comes from sun exposure of the skin, but a small amount can be found in food (e.g. oily fish and eggs). It is important to ensure patients with, or at risk of osteoporosis, are vitamin D replete and supplements are usually indicated for older people (≥65 years) without the need for testing, with a starting dose of 800 international units daily. The Royal Osteoporosis Society (ROS) have a practical clinical guideline for the investigation and management of vitamin D deficiency. (Royal Osteoporosis Society 2017)

Lifestyle Measures

Patients should be informed of the benefits of smoking cessation, drinking alcohol within recommended limits and maintenance of a healthy BMI, especially if underweight.

Physical Activity

For exercise to be most effective in increasing bone strength patients should be encouraged to undertake a combination of impact exercise and progressive resistance training on at least two to three days per week. (Brooke-Wavell 2022) For people with, or at risk, of osteoporosis the benefits of exercise typically outweigh the risks. (Brooke-Wavell 2022) More tailored guidance, and physiotherapy referral may be required for patients with vertebral fractures or at high risk of falls. The ROS has practical ‘how to’ leaflets and videos on their website. (Royal Osteoporosis Society 2018)

Falls Prevention

Most non-vertebral fractures occur following a fall. In patients at risk of falls consider referral to a multi-disciplinary falls clinic. Exercise is recommended to reduce the risk of falls by improving balance and muscle strength. (Brooke-Wavell 2022)

Pharmacological Treatment

Oral treatments in primary care

Oral treatments in primary care are suitable for primary prevention (people who have not previously fractured), secondary prevention (people who have sustained a fragility fracture) and those who do not meet the criteria for referral (see following section). Oral bisphosphonates are the most commonly prescribed but other options may include hormone replacement therapy and raloxifene (not discussed here).

Oral bisphosphonates include alendronate 70mg weekly, risedronate 35mg weekly and ibandronate 150mg monthly. They have been shown to reduce the risk of hip fracture (except for ibandronate for which there is no available evidence), vertebral fracture and non-vertebral fracture.

The most common side effects are gastrointestinal (nausea, dyspepsia, gastritis, and abdominal pain) and are most likely to occur in the first month after treatment initiation. Oral bisphosphonates should be avoided if there is significant history of oesophageal disease eg strictures.

Osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) is a rare possible long-term issue that affects less than 1 in 1000 people taking osteoporosis medicines for 5 years or more. ONJ leads to delayed jawbone healing (>8 weeks) following exposure to osteoporosis medicines. (Khan et al, 2015) The Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme (2017) has produced a helpful guideline on patients receiving osteoporosis medications.

Atypical femoral fracture (AFF) is a rare possible long-term issue that affects less than 1 in 1000 people taking osteoporosis medicine for 5 years or more. An AFF occurs with little or no force in people taking osteoporosis medicines. (Shane et al 2014) Patients should be advised to report any thigh or groin pain whilst on osteoporosis medicines as this can often precede fracture by many weeks. If an AFF is suspected, then seek orthopaedic advice.

To aid absorption and reduce the risk of gastrointestinal side effects patient should be advised to take oral bisphosphonates:

- first thing in the morning (before any other medications and food/drink);

- with a glass of water (not less than 200ml);

- by swallowing the tablet whole (not chewing or attempting to dissolve it).

They should then remain upright (either sitting or standing) for at least 30 minutes.

Existing sources of patient information often focus on the harm rather than the benefits of osteoporosis medications. (Crawford-Manning et al, 2014) Therefore, it is important to balance the benefits with potential harms when discussing osteoporosis medications with patients. (Bullock et al 2021) See Table 2 for our top tips.

Table 2. Oral osteoporosis medication communication tips

| Why? – treatment is recommended | Why Not? – consider the possible harms | How? – practical issues |

|---|---|---|

Explain why treating osteoporosis is important:

|

Ask about patient concerns:

|

Explain how to take the medication and why this is the case:

|

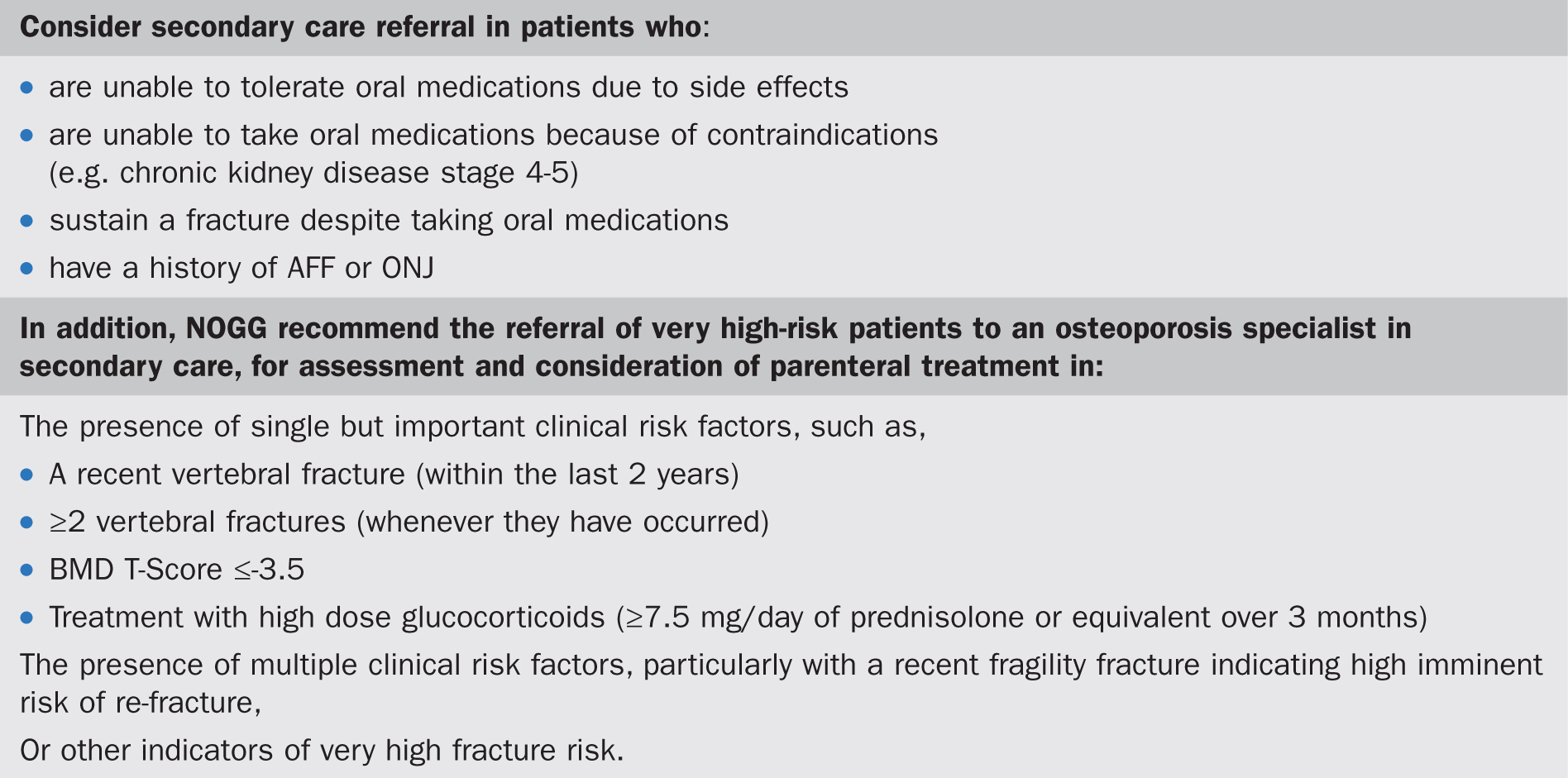

Patients who require referral

Instances when to consider referral are described in Figure 2.

Injectable treatment options

These options are briefly outlined here but a more comprehensive overview can be found in the NOGG guidance. In some areas denosumab is given in primary care with a ‘shared care agreement’ with a specialist secondary care service, but other drugs listed here are secondary care prescribed.

Denosumab

Denosumab is a fully humanised monoclonal antibody against RANK ligand. It is given by subcutaneous injection at a dose of 60mg every six months. It is important to note that denosumab should not be stopped without prior planning; denosumab cessation leads to rapid reductions in BMD and increased risk of vertebral fracture. Therefore, it is important that doses are given on time, and if stopped, its effect must be ‘locked in’ by an alternative osteoporosis medication to reduce subsequent bone loss. (Tsourdi et al, 2021)

Intravenous bisphosphonates

Intravenous bisphosphonates include Zoledronate which is given as a yearly infusion. Intravenous administration may be associated with a short lived ‘influenza type reaction’ but gastrointestinal side effects are less likely.

Teriparatide

Teriparatide is recombinant human parathyroid hormone with an anabolic effect, given by subcutaneous injection at a dose of 20mcg daily for two years. It is reserved for those individuals at very high fracture risk with a low T-score.

Romosozumab

Romosozumab is a humanised monocolonal antibody that binds to and inhibits sclerostin. It is given by subcutaneous injection at a dose of 210mg once monthly for 12 months. Romosozumab use is recommended for postmenopausal women who have had a major osteoporotic (NICE 2022) fracture (hip, spine, forearm, humerus) within 24 months, (with particular priority to people with:

- a BMD T-Score ≤-3.5 (at the hip or spine), or

- a BMD T-score ≤-2.5 (at the hip or spine) and either

- vertebral fractures (either a vertebral fracture within 24 months or a history of ≥2 osteoporotic vertebral fractures), or

- very high fracture risk (e.g., as quantified by FRAX). (NOGG 2022)

Medication reviews

Patient persistence and adherence to oral bisphosphonates is poor and reduces over time. (Imaz et al 2010, Fatoye et al 2019) It is estimated that at one year the persistence rate with oral bisphosphonate is between 16-60% and this subsequently leads to a decrease in the clinical and economic benefits of drug therapy. (Hiligsmann et al 2019) The reasons for this are multi-dimensional but lack of follow-up and monitoring appear to be important factors.

Follow-up and medication reviews are recommended 3 months after starting treatment and then yearly. An osteoporosis medication review should include:

- asking about adverse effects, symptoms of AFF and dental problems;

- asking about adherence to treatment, including the recommended method of taking treatment;

- asking about further fractures and falls;

- consideration of secondary care advice and guidance if there is a history of further fracture(s) or if the patient is not tolerating treatment. (NICE 2017)

There is no agreement on the optimal way of monitoring osteoporosis. There may be local guidelines in your area about when to repeat DXA scans.

Duration of treatment

Oral bisphosphonates should be prescribed for 10 years in the following people:

- Age ≥70 years at the time that the bisphosphonate is started;

- Previous history of a hip or vertebral fracture(s);

- Treated with oral glucocorticoids ≥7.5 mg prednisolone/day or equivalent.

Anyone without one of these features can receive 5 years of treatment. At 5-year review, a reassessment is indicated which may include BMD measurement. Those who have experienced one or more fragility fractures during the first 5 years of treatment and who continue to have osteoporotic BMD should have a 10-year course.

After 5 or 10 years, as appropriate, treatment should be paused. The treatment will continue working (as it lasts in the bone for up to 2 years) but it gradually reduces in its effect allowing natural repair and healing processes, and reducing the risk of rare adverse events. The pause should be for two years in patients receiving alendronate or 18 months for patients receiving either ibandronate or risedronate. Following this time re-assessment is indicated to see if treatment should be restarted. Additionally, if a fracture occurs in the period off bisphosphonate this should prompt an earlier fracture risk assessment and re-initiation of treatment if indicated.

Conclusion

Primary care practitioners play an essential role in the identification of people with, or at risk of, fragility fracture, performing fracture risk assessments, commencing osteoporosis medications, monitoring adherence to treatment, and identifying those at very high fracture risk who may benefit from secondary care review. By effectively addressing these aspects of osteoporosis care they are crucially preventing further costly and potentially life-altering fragility fractures.