Dysphagia literally means difficulty eating, drinking or swallowing (Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists (RCSLT). (2022). Intact motor and nervous systems are essential to enable normal swallowing. Around 5.2 million people, one adult in 8, in the UK have dysphagia (Boaden et. al, 2019). It becomes more common in older age and is associated with neurological problems and frailty (Cohen et. al, 2021: Knott, 2021).

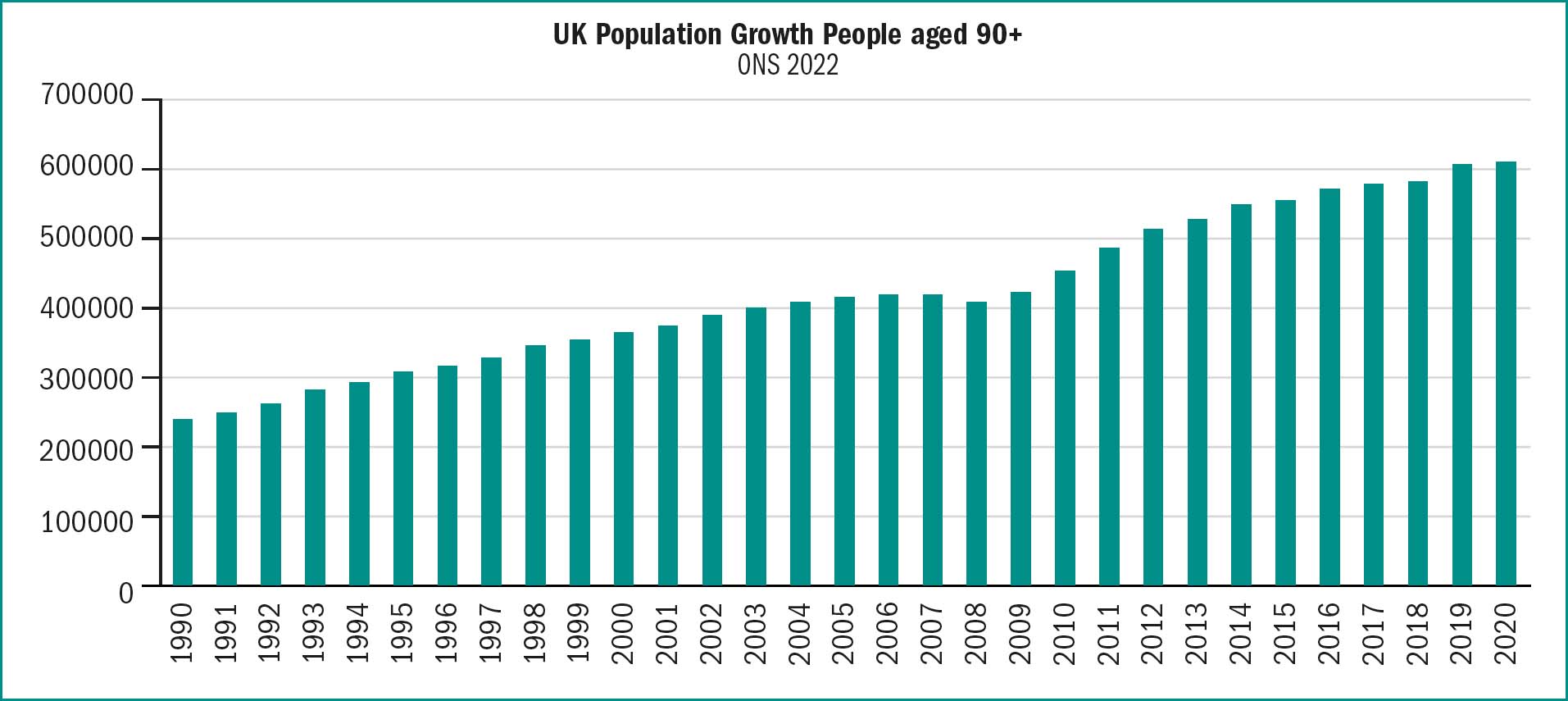

Increasing numbers of people are at risk of dysphagia as the prevalence of conditions that affect swallowing rises with age (Patel et. al, 2018: Cohen et. al, 2021). The number of people aged 90 years and over in the UK has increased by more than 250% in the last 30 years, and was 609,503 in mid-2020 figure one illustrates this (ONS, 2021).

A National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death group (NCEPOD) (2021) review aimed to identify ways to improve the care and treatment of all people with dysphagia. This found that hospitals needed to improve care of people known to have dysphagia, screening processes, referral to speech and language therapists and communication with specialists within the hospital. The review found that people with dysphagia, their care givers and staff who would be providing care on discharge were not always given sufficient information (NCEPOD, 2021).

The nurse working in primary care may be the person who first identifies dysphagia. The individual may need support and advice from the nurse on how to manage dysphagia.

What is dysphagia?

An individual requires intact motor and nervous systems to swallow normally. When there are problems the person can develop dysphagia, difficulty eating, drinking or swallowing (Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists (RCSLT) (2022).

There are four phases in a normal swallow and these are illustrated in Table 1.

| Phase | Mechanism | Possible problems |

|---|---|---|

| Oral Preparatory Stage | Food is ground, chewed and mixed with saliva to form a bolus | Lack of teeth, difficulty biting and chewing. Lack of saliva to form a bolus |

| Oral | Food is moved back through the mouth with a front-to-back squeezing action, performed primarily by the tongue | Tremors of the tongue e.g., in Parkinson's disease and reduced tongue movement e.g., due to stroke (Menon,2022). |

| Pharyngeal | The food enters the upper throat area The soft palate elevates The epiglottis closes off the trachea, as the tongue moves backwards and the pharyngeal wall moves forward These actions help force the food downward to the oesophagus. | Neurological disease, head and neck surgery, radiotherapy to mouth and throat |

| Oesophageal | Muscles propel food through the oesophagus. The oesophageal sphincter opens and closes efficiently. The bolus is moved to the stomach | Oesophageal stricture, malignancy, medical induced oesophagitis and dysmotility and dysmotility secondary to disease (Le, et. al,2023). |

(Author's own work)

There are two distinct types of dysphagia, oropharyngeal and oesophageal dysphagia.

Oropharyngeal dysphagia is described as difficulty initiating a swallow or passing food through the region of the mouth or throat (Menon, 2022). Oesophageal dysphagia refers to difficulty in transferring material down the oesophagus in the retrosternal region (Li et. al, 2023: Malagelada, et al. 2015).

Oropharyngeal dysphagia is underdiagnosed and under treated. It can affect up to 50% of older people and 50% of people with neurological conditions and is associated with aspiration, severe nutritional and respiratory complications and even death (Menon, 2022).

Oesophageal dysphagia is caused by diseases affecting the enteric nervous system and/or oesophageal muscular layers. It occurs less often than oropharyngeal dysphagia but is more commonly diagnosed despite less severe symptoms (Clavé & Shaker, 2015).

Causes of dysphagia

Dysphagia is more common in older people and affects 5–34% of those living at home (Madhavan, et. al, 2016). The prevalence of conditions that affect swallowing rises with age (Patel et. al, 2018: Cohen et. al, 2021). Increasing numbers of people are at risk of dysphagia due to population ageing (Saez, Harrison, & Hill 2023).

Dysphagia is a symptom that may occur because of a number of conditions. It is more common in older adults but may also occur in younger adults and in children. Causes can be categorised as obstructive, neurological and others. Table 2 outlines causes of dysphagia (Knott, 2021).

| Obstructive | Neurological | Other |

|---|---|---|

| Gastro-oesophageal reflux ± stricture. | Cerebrovascular event or brain injury | Pharyngeal pouch. |

| Eosinophilic oesophagitis | Parkinson's disease and other degenerative disorders. | Globus hystericus. |

| Infective oesophagitis | Diffuse oesophageal spasm | External compression (e.g., mediastinal tumour, or associated with cervical spondylosis). |

| Oesophageal cancer. | Syringomyelia or bulbar palsy | Inflammation and infectione.g., tonsillitis, laryngitis. |

| Gastric cancer. | Myasthenia gravis. | |

| Pharyngeal cancer. | Multiple sclerosis. | |

| Post-cricoid web | Myopathy (dermatomyositis, myotonic dystrophy) | |

| Foreign body (acute). | Chagas' disease. | |

| Oesophageal rings. | Achalasia. | |

| Motor neurone disease |

(Author's own work)

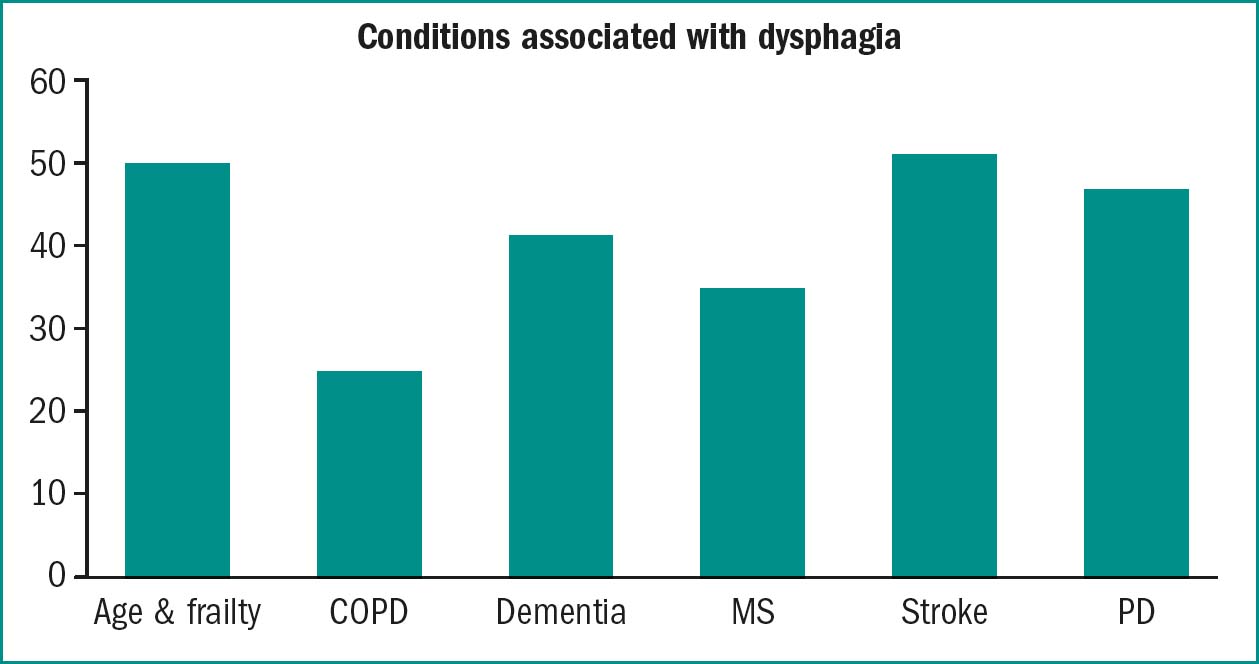

Dysphagia may not always be diagnosed because the individual adapts to the dysphagia and does not seek medical help. Although a person may develop complications of dysphagia such as weight loss or chest infections healthcare staff may not consider that dysphagia as a contributing factor (Clavé & Shaker, 2015). It's important to be alert to the clinical features of dysphagia and to check if the person if experiencing swallowing difficulties when assessing and treating those at risk of dysphagia (Boaden et. al, 2019). Certain people have greater risks of dysphagia than others (see table three and figure two).

| Condition | Prevalence dysphagia |

|---|---|

| Age associated frailty | 51–53 % (Patel et. al, 2018: Cohen et. al, 2021). |

| Chronic obstructive airways disease (COPD) | 27% (Turley & Cohen, 2009: Lin & Shune, 2020) |

| Dementia | 13–86% depending on type of dementia and severity (Espinosa-Val, et. al, 2020). |

| Multiple Sclerosis | 31–43% (Aghaz et al, 2018) |

| Stroke | 13–94% dependent on location and size of lesion (Arnold et, al 2016) |

| Parkinson's Disease | 11% and 87% depending on the disease stage, the disease duration, and the assessing method (Schindler et al, 2021) |

(Author's own work)

Identifying people with dysphagia

The best way to identify dysphagia is to routinely ask people presenting at the surgery or in the community if they have any problems with swallowing. A survey of 791 people aged 60 and over attending 17 community pharmacies was carried out by pharmacists and found that almost 60% had difficulty swallowing medication, they reported opening tablets and crushing medications. Older people were asked if they had informed their GPs and 72% reported that they hadn't been asked (Strachan & Greener, 2005). Table 4 outlines the clinical features of dysphagia (Knott, 2021)

| Coughing/choking during or after meals |

| Unintentional weight loss |

| Throat clearing |

| Wet gurgling voice after eating |

| Fever |

| Chills |

| Changes in breathing |

| Food or liquids traveling back up through your throa or nose after swallowing |

| Feeling of food or liquids being “stuck” in the throa or chest |

| Pain while swallowing |

| Heartburn |

| Dehydration |

| Excessive secretions |

| Leakage of food or saliva from mouth |

Red flags

The term ‘red flags’ was introduced in the 1980s and is used to signal that the person requires urgent medical attention. (Ramanayake & Basnayake, 2018).

NICE (2021) provides information on what assessments should be carried out in primary care and when to consider a possible cancer diagnosis and to refer under the two-week rule, table five provides details.

| Symptom | Possible cancer | Referral recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Appetite loss (unexplained) | Several, including lung, oesophageal, stomach, colorectal, pancreatic, bladder, or renal | Carry out an assessment for additional symptoms, signs, or findings that may help to clarify which cance is most likely Offer urgent investigation or a suspected cancer pathway referral (for an appointment within 2 weeks) |

| Weight loss (unexplained) | Several, including colorectal, gastro-oesophageal, lung, prostate, pancreatic, or urological cancer | Carry out an assessment for additional symptoms, signs, or findings that may help to clarify which cance is most likely Offer urgent investigation or a suspected cancer pathway referral (for an appointment within 2 weeks) |

| Upper abdominal mass consistent with stomach cancer | Stomach | Consider a suspected cancer pathway referral (for an appointment within 2 weeks) |

| Dyspepsia (treatment-resistant), age 55 years and over | Oesophageal or stomach | Consider non-urgent direct access upper gastrointestinal endoscopy |

| Dyspepsia with weight loss, age 55 years and over | Oesophageal or stomach | Offer urgent direct access upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (to be performed within 2 weeks) |

| Dyspepsia with raised platelet count or nausea or vomiting, age 55 years and over Dysphagia | Oesophageal or stomach Oesophageal or stomach | Consider non-urgent direct access upper gastrointestinal endoscopy Offer urgent direct access upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (to be performed within 2 weeks) |

| Haematemesis | Oesophageal or stomach | Consider non-urgent direct access upper gastrointestinal endoscopy |

| Haemoglobin levels low with upper abdominal pain, age 55 years and over | Oesophageal or stomach | Consider non-urgent direct access upper gastrointestinal endoscopy |

| Nausea or vomiting with raised platelet count or weight loss or reflux or dyspepsia or upper abdominal pain, age 55 years and over | Oesophageal or stomach | Consider non-urgent direct access upper gastrointestinal endoscopy |

| Platelet count raised with nausea or vomiting or weight loss or reflux or dyspepsia or upper abdominal pain, age 55 years and over | Oesophageal or stomach | Consider non-urgent direct access upper gastrointestinal endoscopy |

| Reflux with raised platelet count or nausea or vomiting, age 55 years and over | Oesophageal or stomach | Consider non-urgent direct access upper gastrointestinal endoscopy |

| Reflux with weight loss, age 55 years and over | Oesophageal or stomach | Offer urgent direct access upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (to be performed within 2 weeks) |

| Upper abdominal pain with low haemoglobin levels or raised platelet count or nausea or vomiting, age 55 years and over | Oesophageal or stomach | Consider non-urgent direct access upper gastrointestinal endoscopy |

| Upper abdominal pain with weight loss, age 55 years and over | Oesophageal or stomach | Offer urgent direct access upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (to be performed within 2 weeks) |

| Weight loss with upper abdominal pain or reflux or dyspepsia, age 55 years and over | Oesophageal or stomach | Offer urgent direct access upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (to be performed within 2 weeks) |

| Weight loss with raised platelet count or nausea or vomiting, age 55 years and over | Oesophageal or stomach | Consider non-urgent direct access upper gastrointestinal endoscopy |

Aspiration is the term used when foods or fluid passes through the vocal folds and enters the airway. It can be caused by impaired laryngeal closure or because of the overflow of food or liquids retained in the pharynx. The larger the volume of fluid or food aspirated the greater the problem. Food and fluids can be aspirated into the trachea or more deeply. Deep aspiration is more dangerous than shallow aspiration. Acid material (such as orange juice) can set up an inflammatory reaction in the lungs and cause serious damage. Aspiration that is not accompanied by a cough is known as “silent aspiration”. This is much more dangerous than aspiration accompanied by a cough because food or fluids penetrate the airway and move deep into the lungs causing major respiratory problems. (Jamróz, et al. 2024).

If the person is clinically unwell and has a suspected aspiration pneumonia the clinician should treat or escalate the case using national guidance and local protocols. If for example the national early warning score is 5 or more the clinician should suspect sepsis and escalate (NICE, 2024). If the person has an unsafe or possibly unsafe to swallow then urgent medical referral is required.

Assessment in community settings

If a person has a new or deteriorating swallow the nurse should follow local protocols. These may involve completing a dysphagia screen and possibly carrying out an initial assessment of swallowing.

History taking can often enable the clinician to determine if urgent medical referral is required. If the person is unable to swallow and has not been able to drink sufficient fluid to maintain health an urgent referral is required. In some cases, careful history taking and examination can enable the clinician to determine the cause of dysphagia.

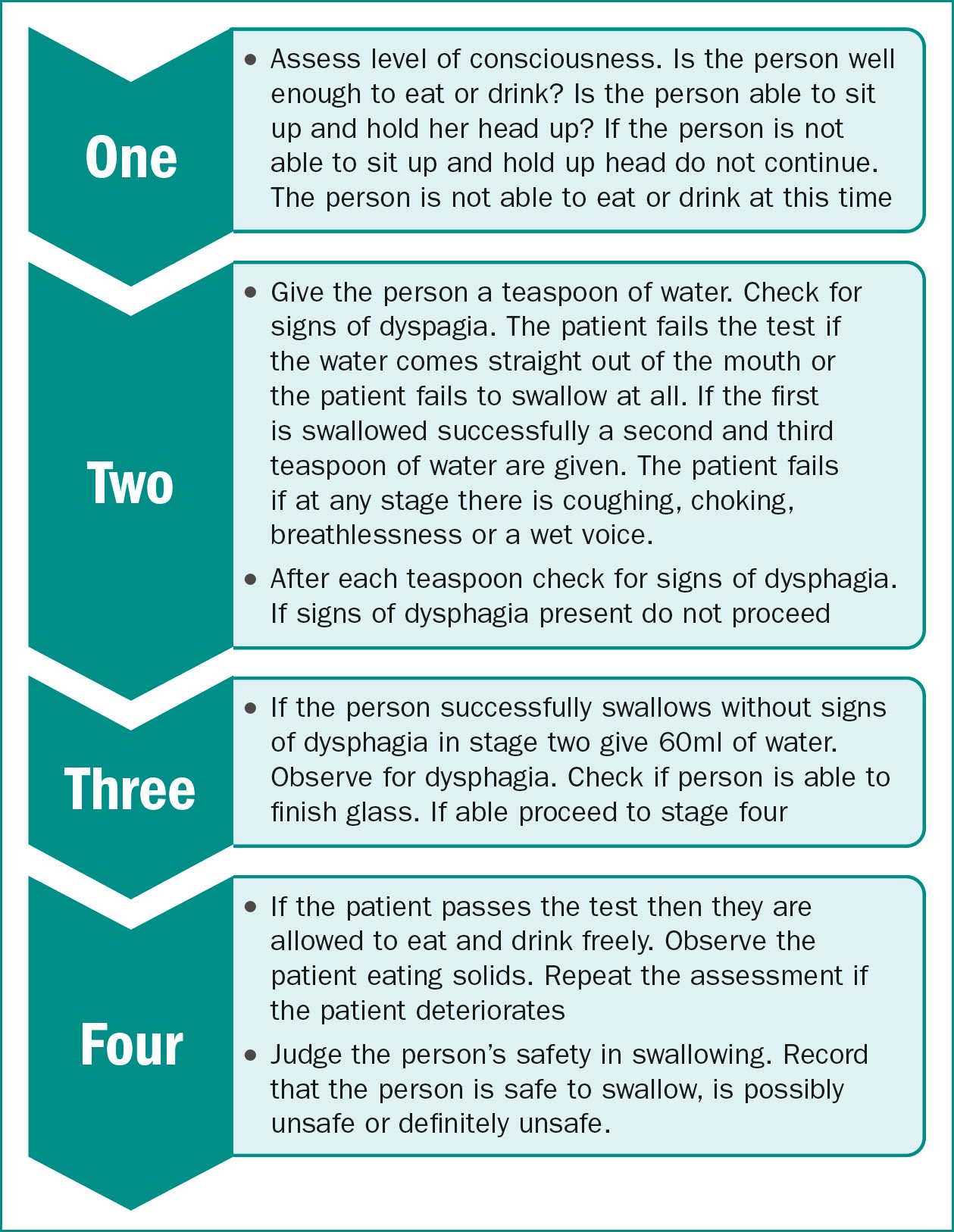

Bedside swallowing tests have been developed to screen for oropharyngeal dysphagia. A systematic review of these tests identified four tests with sensitivity of ≥70% and specificity of ≥60% (Kertscher et. al, 2014). These were, the Toronto bedside swallowing screening test (TOR-BSST©) (Martino et. al, 2009), the volume-viscosity swallowing test (V-VST)(Clavé et. al, 2008), the 3-ounce water swallow test (Suiter & Leder, 2008) and the cough test (Wakasugi et. al, 2008). A test often used in general practice is based on the 3 ounce swallow test (GP Notebook, 2018). NB 3 ounces is equivalent to around 90ml.

In primary care settings the level of assessment will vary according to local policy and the level of training the nurse has received. The nurse should be able to take a history, examine the person for signs of illness or dehydration and carry out a dysphagia screen. In some areas the nurse may be able to carry out a bedside swallowing assessment. If person is unwell, dehydrated or there are concerns about the person's ability to swallow safety urgent referral to hospital is required. The person will then be assessed by medcal staff and SLTs.

Figure 3, based on GP notebook 2018, illustrates the components of an initial swallowing assessment.

Oral health and dysphagia

Poor oral health can contribute to problems with dysphagia, tooth loss, gum disease and infection affects the ability to bite and chew (Cichero, 2020). The nurse should look in the person's mouth to check if oral health problems are contributing to dysphagia. If for example the person has a fungal infection such as candida this should be treated. If teeth are decayed or damaged advise the person to seek dental treatment.

Specialist referral and investigations

People identified as having dysphagia are normally referred to a speech and language therapist (SLT) for further in-depth assessment. Assessment often includes videofluroscopy (VFS). VFS is a modified form of the barium swallow X-ray examination. It evaluates oropharyngeal swallowing physiology and anatomy as the patient eats and drinks a radiopaque substance such as barium sulphate. The radiopaque substance may be mixed with food or drink. The moving images of the oropharyngeal swallow are recorded for interpretation. The SLT may recommend dietary and fluid modification and other treatments. These aim to improve nutrition and hydration and reduce the risks of aspiration pneumonia (Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists, 2013).

The importance of fluids and diet

Dysphagia increases the risk of malnutrition and dehydration and can affect health and quality of life.

(Azer, Kanugula & Kshirsagar, 2024; Ueshima et al, 2021) In many cases it is not possible to treat dysphagia and the aims of care are to maintain nutrition and hydration reduce the risk of aspiration pneumonia and ensure that the person is able to take medication. The key to maintaining nutrition and hydration in people with dysphagia is to promote safe swallowing and to ensure that the person has food and fluids which are of the appropriate texture and thickness. Table six provides guidance on how to advise a person or care givers on safe swallowing.

| Sit upright at 90 degrees when eating and drinking |

| Do not eat or drink when slouched or lying down |

| Take small bites of food |

| Take small sips of fluid |

| Do not gulp drinks |

| Eat slowly |

| Chew foods well before swallowing |

| Make sure you have swallowed your food or drink before taking more |

| Don't wash down your food with drinks |

| Don't talk when you have food in your mouth |

| Heartburn |

| Dehydration |

| Excessive secretions |

| Leakage of food or saliva from mouth |

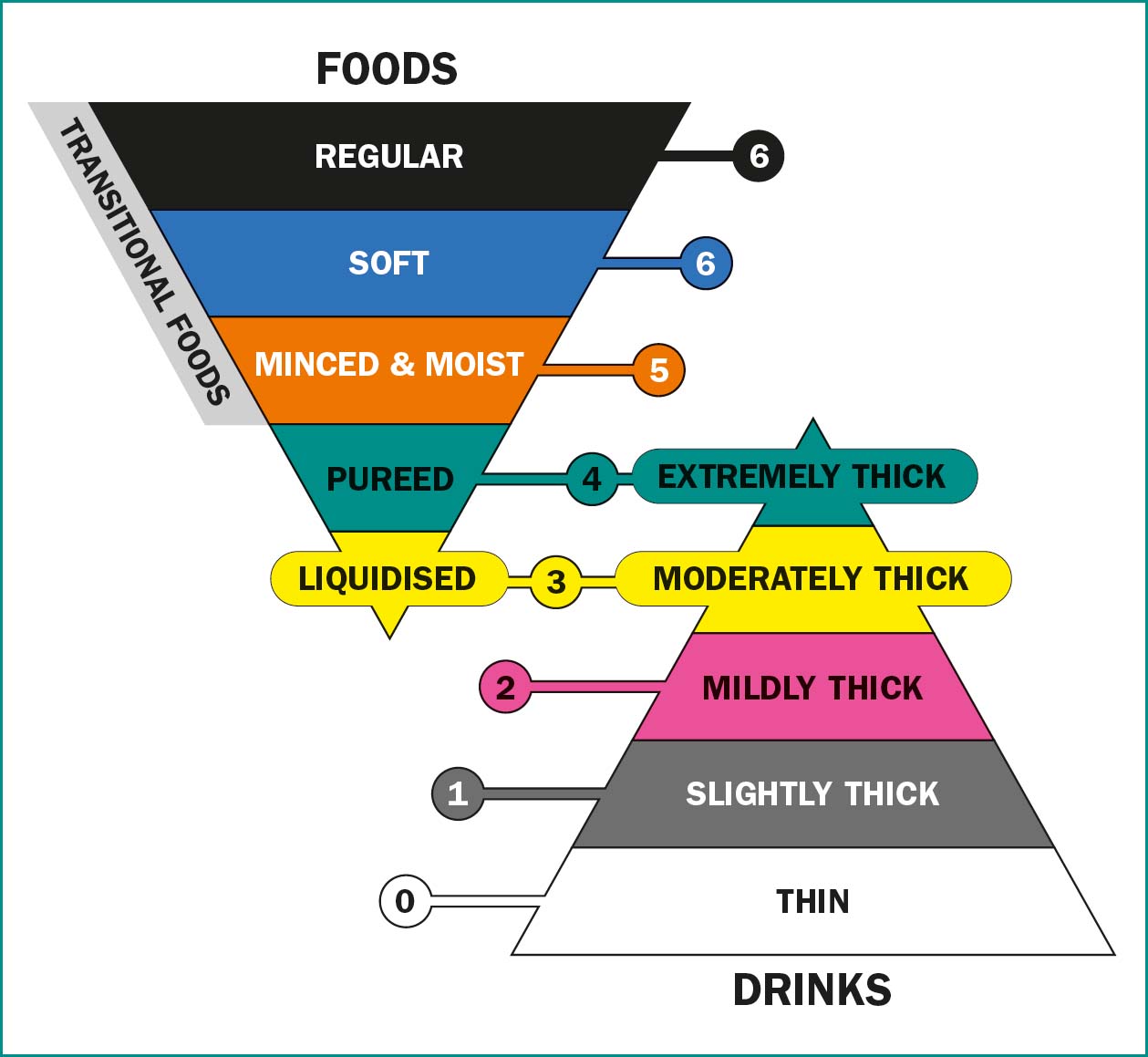

The UK adopted the international framework descriptors for levels of thickness in 2019, all services in the UK (see figure 4) (IDDSI, 2019)

Normal fluids, referred to as ‘thin fluids’ in the IDDSI framework are more likely to aspirated than thicker fluids. Fluid that is thickened is stickier and is easier to control than normal fluids. This reduces the risk of aspiration (Masuda et. al, 2022). Table 7 illustrates examples of fluids and thickness

| Consistency | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Thin/normal | Still water | Water, tea, coffee without milk, diluted squash, spirits, wine |

| Slightly thick/naturally thick | Leaves a coating on an empty glass | Full cream milk, oral nutritional supplements |

| Mildly thick/syrup thick/stage 1 | Can be drunk through a straw or from a cup Leaves thin coat on the back of a spoon | Smoothie, milkshake |

| Moderately thick/custard thick/stage 2 | Cannot be drunk from a straw Can be drunk from a cup Leaves thick coat on back of a spoon | Custard. |

| Weight | Fluid requirement |

|---|---|

| 35–44kg | 1200 |

| 45–54kg | 1500 |

| 55–64kg | 1800 |

| 65–74 | 2100 |

| ≥75 | 2400 |

Fluid requirements

It is important to ensure that people with dysphagia drink sufficient fluids. NICE (2017) guidance recommends 25–30ml of fluid per kilo per day. NICE recommends that clinicians consider less fluid: 20–25ml/kg/day in frail older people patients with renal impairment or cardiac failure. If a person is obese ideal body weight should be used to calculate fluid requirements.

Problems with thickened fluids

Thickening agents, may be starch or gum based and are used to thicken fluid. The rationale is that thick fluids have a higher viscosity and can compensate for a swallowing deficit by slowing down the flow of fluid from the mouth to the oropharynx, allowing time for glottis closure which could potentially reduce the risk of aspiration (O'Keeffe, 2018).

Many people who have dysphagia and require thickened fluids are dehydrated and there have been concerns that thickening fluid reduces bioavailability and prevents the body from using the fluid normally. Cichero (2013) examined this issue and found that bioavailability of fluid was not affected by the type of thickener or by the viscosity of the liquid. People who have thickened fluids are dehydrated because they drink less than people on normal fluids (Garcia & Chambers, 2010). There are a number of factors affecting fluid intake. Starch based thickeners give fluids a starchy flavour and a grainy texture. These affect the pleasure of drinking a fluid (Garcia & Chambers, 2010). Gum based thickeners do not produce grainy textures and do not make people feel full up in the same way as starch based thickeners. All types of thickener reduce the flavour of a drink and thicker liquids have less flavour than thinner liquids (Cichero, 2013). The greater the level of thickener the lower the level of fluid intake (Vivanti et. al, 2009).

The Royal College of Speech and Language Therapy comment that it is becoming increasingly recognised that aspiration does not always lead to poor health outcomes and frequently modifying the texture of food and drink can lead to major negative impact on the well-being of the person. They now recommend that anyone being placed on a significantly modified diet should be reviewed regularly (Royal College of Speech and Language Therapy, ND). Cicero (2013) recommends that clinicians prescribe the minimal level of thickness needed for swallowing safety and optimise management of individuals with dysphagia. O'Keefe (2018) points out that currently we lack robust evidence that thickening agents reduce pneumonia in dysphagia.

Choice

Sometimes as professionals we concentrate so much on evidence-based practice and doing the right thing that we forget that people have a choice about whether to accept or decline healthcare advice and interventions. O'Keefe (2018) reminds us that modified diets worsen the quality of life of those with dysphagia, and non-compliance is common. He states that patients should be given adequate information, about the potential risks and impact on quality of life as well as the possible benefits in order to make choices about modified food and fluids.

Medication

People with dysphagia may struggle to swallow medication and all medication should be reviewed. The review should consider if a specific medication is necessary, if any medication is contributing to dysphagia, if easier to swallow medication is available and if medication can be safely crushed. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) such as omeprazole may be prescribed to people who suffer from a reflux of gastric acid into the oesophagus as this can lead to or worsen dysphagia (Philpott et. al, 2017).

Skilful holistic care

As the population ages people are living with multiple long term conditions and they require skilful holistic care. There is a tendency in acute care for the person to be seen as a series of conditions rather than a person with a number of interacting conditions. Nurses working in primary care are in a unique position to develop an overview of the person's health and to provide support to promote the best possible health. In people with dysphagia this will include routine monitoring of nutritional status and supporting the person.

Conclusion

Dysphagia can have a major impact on a person's life. It can affect the ability to remain hydrated and nourished and increase the risk of infection and ill health. The nurse can by supporting the person with dysphagia and skilfully optimising health, make a real difference to a person's quality of life.

Resources

Helpful video guidance of how to test drink thickness using a 10ml slip tip hypodermic syringe here: http://iddsi.org/framework/drink-testing-methods/. There are also useful ways of checking food textures on the site The BAPEN tool is available on line. It consists of three modules, Each module includes case studies and care plans appropriate for the work place and an online assessment, together with the ability to print off certificates of achievement. Key features include:

BAPEN also provides a free downloadable booklet on the use of MUST. http://www.bapen.org.uk/screening-and-must/must/introducing-must