Allergic rhinitis is described as an immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated inflammatory disorder of the nasal mucosa triggered by exposure to an allergen (Bousquet et al, 2008). It is characterised by symptoms including rhinorrhoea, sneezing, nasal obstruction and itching, which have a great impact on the patient's quality of life (Scadding et al, 2017). It is a global health problem that causes major disease and disability affecting work or school performance, social life and sleep (Bousquet et al, 2008).

Rhinitis affects 26% of adults and 10–15% of children in the UK, reaching its peak prevalence in adults aged between 30–40 years old and showing remission throughout adult life. In the UK and Western Europe, there has been a remarkable increase in the prevalence over the last four to five decades. Globally, there seems to be an association between economic and industrial development and the occurrence of allergic rhinitis (Scadding et al, 2017).

Allergic rhinitis carries a cost burden to the healthcare system due to costs resulting from pharmaceutical therapies and outpatient visits for review of disease management (Tesch et al, 2020). However, there are also indirect costs incurred through reduction in productivity due the impact of the symptoms on the patient's quality of life. This suggests an underestimation of the economic impact of allergic rhinitis (Bousquet et al, 2008). In addition, allergic rhinitis is linked to an increased risk of asthma development and both diseases are believed to be different expressions of the same inflammatory process. Therefore, costs incurred due to asthma exacerbations need to be taken into consideration, as these could also potentially lead to hospitalisations in the most severe cases (Tesch et al, 2020).

Symptoms of allergic rhinitis

Exposure to allergens leads to early and late phase allergic reactions. The early phase reaction is characterised by sneezing and rhinorrhoea as a result of histamine, prostaglandin and leukotriene release by the activated mast cells. The late phase consists of the migration of several inflammatory cells including eosinophils, mast cells and T cells to the nasal mucosa leading to remodelling, which causes nasal obstruction. This damage in the nasal mucosa can also increase the hyperresponsiveness to normal stimuli contributing to the development of the symptoms mentioned above (Min, 2010).

Allergic rhinitis can be classified depending on the frequency and severity of symptoms as per the World Health Organization Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) guidelines (Bousquet et al, 2008). Intermittent symptoms refer to symptoms that appear less than 4 days a week or less than 4 consecutive weeks, whereas persistent symptoms are present for more than 4 days a week or over 4 consecutive weeks. If symptoms are not described as bothersome and do not affect sleep, work or school, they are classified as mild; however, those that are distressing and disrupt daily activities are defined as moderate–severe symptoms (Table 1).

Table 1. Classification of allergic rhinitis according to ARIA guidelines

| Intermittent | Means that the symptoms are present:

|

| Persistent | Means that the symptoms are present:

|

| Mild | Means that none of the following items are present:

|

| Moderate/Severe | Means that one or more of the following items are present:

|

Allergic rhinitis can be further sub-divided into seasonal and perennial (Bousquet et al, 2008). Seasonal rhinitis is often caused by outdoor allergens such as pollen or moulds, whereas perennial rhinitis is related to indoor allergens including house dust mite (HDM), animal dander, moulds or insects. Although this classification is not entirely suitable for the description of allergic rhinitis globally, it is useful in the UK. Rhinitis symptoms could also be present in patients without any evidence of allergen sensitisation (negative specific IgE or skin prick test). This is known as non-allergic rhinitis (Bousquet et al, 2008; Scadding et al, 2017).

Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma (the ‘one airway, one disease’ theory)

Allergic rhinitis is one of the major risk factors of asthma development. Allergic rhinitis is present in many patients with asthma, reaching a prevalence of 100% in patients with allergic asthma (Thomas, 2006).

The association between the nose and lungs may be attributed to their anatomical similarities and the protective role that the nose has for the lungs. The nose is responsible for air conditioning of the lower airways as well as warming and humidification, filtering and mucociliary clearance. Inflammation and damage of the nasal mucosa may affect its role, leading to further impact on the lower airways (Togias and Windom, 2004).

In addition, allergic rhinitis is often linked to mouth breathing, which appears to increase the risk of asthma morbidity due to bypassing the protective functions of the nose, resulting in lung function deterioration (Izuhara et al, 2016).

The connection between both allergic rhinitis and asthma is recognised under the concept of ‘one airway, one disease’. Both diseases exhibit the same patterns of inflammation and are described as a single inflammatory process (Bousquet et al, 2008; Bourdin et al, 2009).

The inflammatory changes in the mucosa of the upper and lower airways are similar (Bergeron and Hamid, 2005). Allergen exposure in the nasal mucosa activates the inflammatory cascade, which consists of an early phase response and, in some cases, a late phase response. Allergen binding to IgE receptors leads to degranulation of mast cells, releasing inflammatory mediators including histamine, prostaglandin D2, cysteinyl leukotrienes and neutral proteases. Accumulation of mast cells, eosinophils and basophils can be found in the epithelium of the nasal mucosa in patients with active allergic rhinitis (Bergeron and Hamid, 2005; Jeffery and Haahtela, 2006).

Similarly, early and late phase inflammatory responses may occur in the lung following allergen contact in asthmatic patients. However, the main originator of chronic inflammation in asthma is the CD4 or T-helper lymphocyte, which produces key regulatory cytokines such as interleukin-5 (IL-5) and interleukin-4 (IL-4). In response to this, eosinophils are released into the circulation, which are then retained in the mucosa and migrate to the surface epithelium (Jeffery and Haahtela, 2006). These resemblances in the inflammatory changes, in addition to the structural similarity in the nasal and bronchial mucosa, support the unified airway hypothesis (Bourdin et al, 2009).

Some studies show that bronchial eosinophilic inflammation and hyperresponsiveness can also be triggered by allergen stimulation of the nasal mucosa in patients with allergic rhinitis, even if asthma symptoms are absent. This appears to increase the risk of developing asthma (Riccioni et al, 2002; Boulet, 2003).

Both the bronchial inflammation and hyperresponsiveness are associated with airway remodelling. Despite inflammation process similarities between asthma and allergic rhinitis, the remodelling of the epithelium in the nose appears to be less extensive, and therefore less clinically significant than in the lungs. Differences in remodelling need further study; however, the secretory activity of the smooth muscle cells present in the bronchi and the different embryologic origins of the bronchi and nose may support this (Bousquet et al, 2004).

IgE seems to play a significant role in the pathophysiology of both allergic asthma and allergic rhinitis, and therefore, targeting IgE seems to be the goal of disease management in the most severe cases (Cavaliere et al, 2020). Omalizumab is a monoclonal antibody which selectively binds to IgE and is used for the treatment of severe allergic asthma in eligible patients (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2013). However, omalizumab is currently not licensed for use in allergic rhinitis. Some studies suggest that omalizumab is a safe and effective therapy for the management of allergic rhinitis and concomitant asthma (Tsabouri et al, 2014; Cavaliere et al, 2020).

Management of allergic rhinitis

The aim of the treatment is improving the patient's quality of life by relieving symptoms. Management of allergic rhinitis will encompass a combination of allergen avoidance, pharmacological therapies and patient education and adherence. Allergen avoidance is often difficult, and if symptoms persist, medication should be considered in a stepwise approach according to severity (Scadding et al, 2017). In addition, where concomitant asthma exists, treating asthma will lead to better outcomes (Bousquet et al, 2008; Min, 2010).

Allergen avoidance

Allergen avoidance should be the first step in the management of allergic rhinitis. This is an effective measure as shown in seasonal allergic rhinitis where patients are symptom free outside the pollen season. There is limited information and poor evidence on effective strategies on HDM and pet allergen avoidance; however, there are some practical measures that health professionals can advise patients on (Table 2). Single measures for allergen avoidance have been shown to be ineffective, and therefore combined measures are recommended.

Table 2. Practical measures for allergen avoidance

| House dust mite |

|---|

|

| Pollen (during pollen season) |

|

| Pets |

|

Pharmacological therapy

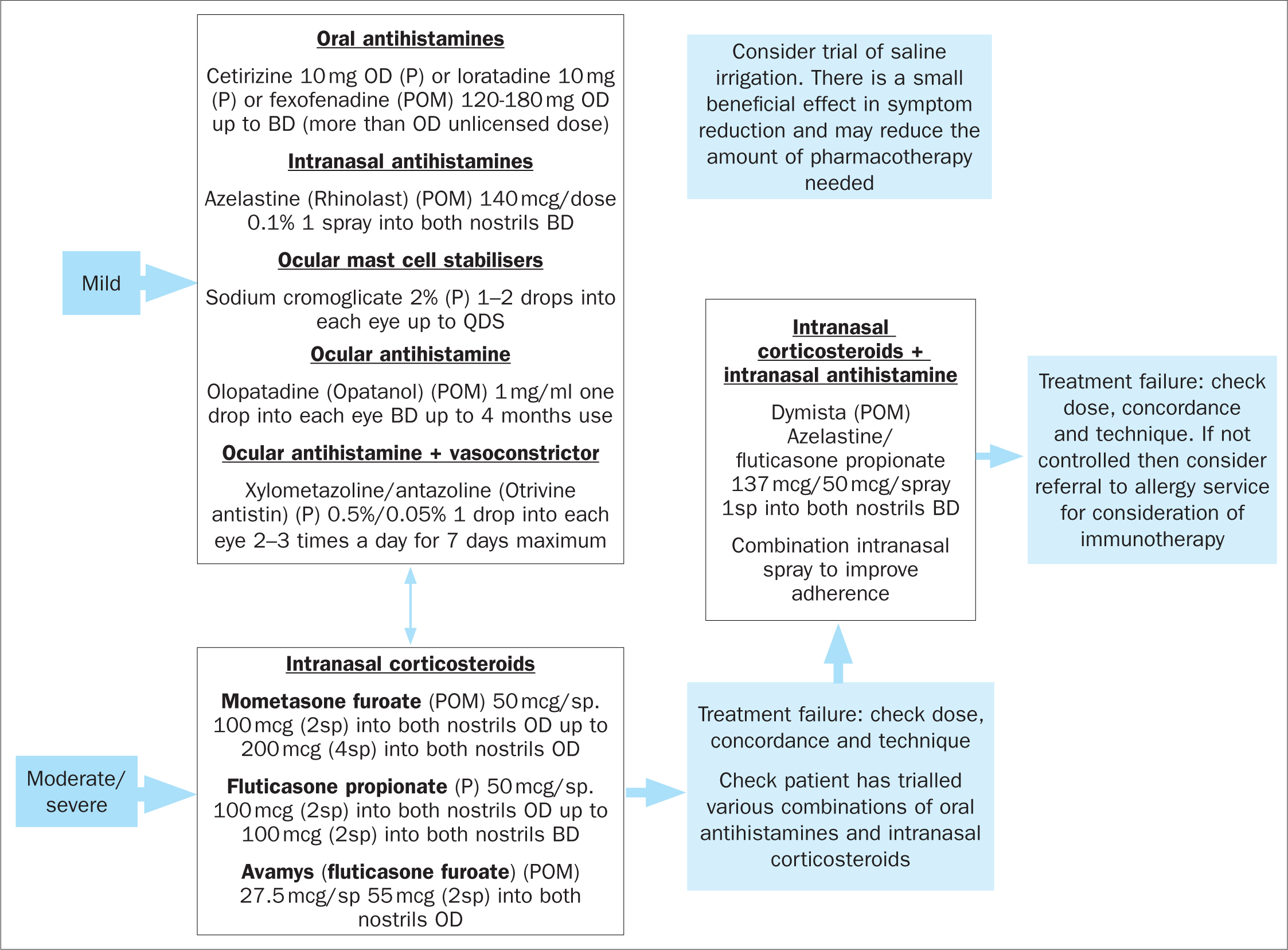

The pharmacological therapies for the management of mild and moderate-severe allergic rhinitis are outlined below (Figure 1).

Oral antihistamines

Oral H1-antihistamines are used as first-line therapy for mild to moderate symptoms. They mainly improve symptoms caused by the release of histamine including itchiness, sneezing and rhinorrhoea (Scadding et al, 2017). Second-generation oral antihistamines (eg fexofenadine, cetirizine) are preferred over first-generation antihistamines in view of their non-sedative and non-anticholinergic properties (Shamsi and Hindmarch, 2000; Liu and Farley, 2005). Second-generation antihistamines are also long-acting, which reduces administration frequency (Scadding et al, 2017).

Intranasal antihistamines

Intranasal antihistamines (currently azelastine is the only available drug in the UK) have shown superiority over oral antihistamines in relieving rhinitis symptoms and decreasing nasal obstruction (Lee and Pickard, 2007; Horak, 2008). Their rapid onset of action means that they can be used as needed, although regular use is clinically more effective. Using oral and intranasal antihistamines concomitantly does not provide additional benefit in relieving nasal symptoms. They are used as first-line therapy for mild-to-moderate intermittent and mild persistent rhinitis (Scadding et al, 2017).

Intranasal steroids

Intranasal steroids are the first line treatment for moderate-severe symptoms and nasal obstruction. They act on all the major symptoms of rhinitis by supressing the inflammatory cascade (Scadding et al, 2017). Topical administration to the nasal mucosa rapidly delivers the drug to the site of disease, while minimising the risk of systemic adverse reactions (Bousquet et al, 2008). Systemic absorption is minimal with fluticasone furoate, fluticasone propionate and mometasone furoate; therefore, treatment with these preparations is preferred (Derendorf and Meltzer, 2008). The maximal effect will be reached 2 weeks after initiation of treatment. Therefore, it is recommended to start treatment 2 weeks prior to the allergen season (Scadding et al, 2017).

Intranasal combination therapy

The combination of fluticasone propionate and azelastine improves nasal congestion and eye symptoms compared to each product alone (Carr et al, 2012). This can be offered as second-line treatment if intranasal antihistamine or steroid monotherapy fails (Scadding et al, 2017).

Leukotriene receptor antagonists

Montelukast has shown comparable efficacy to oral antihistamines, but reduced efficacy compared to intranasal steroids (Wilson et al, 2004; Martin et al, 2006). It is only licensed in the UK for patients with allergic rhinitis who also suffer from asthma (Scadding et al, 2017).

Ocular therapy

Mast cell stabilisers like sodium cromoglycate and nedocromil sodium are effective for eye symptoms, but ineffective for nasal symptoms (Bousquet et al, 2008). They are only used for mild symptoms and sporadic problems during the season (Scadding et al, 2017).

Ocular antihistamines such as olopatadine and azelastine are rapidly effective (<30 min) on nasal or ocular symptoms (Bousquet et al, 2008).

Immunotherapy

Allergen immunotherapy is recommended for patients with a confirmation of IgE sensitivity and uncontrolled symptoms despite maximal pharmacotherapy. Immunotherapy can not only improve symptoms and quality of life but can also reduce the medication required (Bousquet et al, 2008; Scadding et al, 2017). It also has a role in the modification of the natural course of allergic rhinitis, leading to its possible long-term remission (Walker et al, 2011).

Immunotherapy can be administered subcutaneously (SCIT) or sublingually (SLIT) over a 3-year course in the UK. While SLIT can be self-administered at home due to a safer profile, SCIT can only be administered in specialist clinics due to the risk of systemic side-effects such as anaphylaxis or allergic reactions (Scadding et al, 2017).

Education

Education of the patient or patient's carer may increase compliance leading to better treatment outcomes in the management of rhinitis (Bousquet et al, 2008). Discussing the role of the medication and safety profile is essential to ensure patients understand their treatment and engage in the management of their disease (Royal Pharmaceutical Society, 2013). Counselling in nasal spray technique is often overlooked at initiation of therapy. Taking time to teach correct technique will ensure a correct administration to optimise efficacy and reduce undesirable local adverse effects such as nasal crusting or bleeding (Scadding et al, 2017).

How health professionals can optimise allergic rhinitis and asthma care

It is essential for multidisciplinary clinical staff who work in primary or secondary care in asthma or allergy settings to understand this relationship and recognise the presence of both conditions. A combined approach in the treatment of upper and lower airways is needed to obtain better patient outcomes (Bousquet et al, 2008; Min, 2010). This can be supported by appropriate referrals to the relevant specialist for optimisation of therapy. The wider multidisciplinary team including specialist clinical nurses, pharmacists, physiotherapists, dietitians and psychologists can provide a holistic approach to support effective and safe therapy. Appropriate education and counselling during the consultations can also contribute to the optimisation of allergic rhinitis and asthma management (Royal Pharmaceutical Society, 2013).

Conclusion

Allergic rhinitis is a highly prevalent condition worldwide, which involves the inflammation of the nasal mucosa (Bousquet et al, 2008). The main symptoms include itching, runny nose, sneezing and nasal congestion leading to impaired quality of life of patients that suffer from allergic rhinitis (Scadding et al, 2017).

Allergic rhinitis and asthma appear to be considered as one respiratory syndrome due to their similar inflammatory characteristics and the functional complementarity between the nose and the lungs (Bousquet et al, 2008; Min, 2010).

The management of allergic rhinitis includes allergen exposure prevention, pharmacotherapy and patient education (Bousquet et al, 2008; Scadding et al, 2017). However, in view of the links between allergic rhinitis and asthma, a combined strategy to treat both the upper and lower airways may lead to better clinical outcomes (Bousquet et al, 2008; Min, 2010).

KEY POINTS:

- Allergic rhinitis is described as an inflammatory disorder of the nasal mucosa characterised by symptoms including rhinorrhoea, sneezing, nasal obstruction and itching

- Allergic rhinitis is one of the major risk factors of asthma development

- Asthma and allergic rhinitis are described as a single inflammatory disease and recognised under the ‘one airway, one disease’ theory

- The management of allergic rhinitis aims to improve the patient's quality of life by relieving symptoms and includes allergen avoidance, pharmacotherapy and patient education

- A combined strategy to treat both upper and lower airways may lead to better clinical outcomes

CPD REFLECTIVE PRACTICE:

- Why is important to achieve a good control of allergic rhinitis symptoms in asthma patients?

- What clinical considerations would you take and how would you manage a patient with both asthma and allergic rhinitis?

- What are your current consultation practices that allow you to assess proper nasal spray technique and patients' adherence to allergic rhinitis treatments?

- How frequently do you screen for uncontrolled asthma in patients who present to you with allergic rhinitis symptoms?