Respiratory complaints are seen regularly in practice but are often non-specific and can be caused by a variety of different conditions, both respiratory and non-respiratory. Advanced practitioners working in general practice are regularly faced with patients presenting with respiratory problems, either acute or chronic, so a proficiency in respiratory examinations is essential to assess and manage such conditions. It is also essential that advanced practitioners work in line with The Code (Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2018), recognising the limits of their own competence and appropriately referring to another practitioner when necessary. This article will focus on the assessment and examination of the respiratory system, while providing important information on receiving a history from a patient using useful acronyms. Key learning points will include common presentations and differential diagnoses, red flags, and further investigations.

Receiving the history

Taking a patient history is an essential element in establishing a diagnosis and is used to get a deeper understanding of the patient's symptoms. The purpose of a systematic health history is to obtain important and detailed knowledge about the patient, their lifestyle, social supports, medical history, and health concerns, with the history of presenting illness as the focus (Ingram, 2017; Fromage, 2018). This enables the advanced practitioner to gather important information about the patient's underlying medical conditions and the reason they have attended, which will be valuable in formulating a diagnosis (Demosthenous, 2017).

The first part of the history taking process is to establish the details of the presenting complaint. Using a mnemonic assessment tool can be useful for advanced practitioners when trying to explore complex symptoms, such as breathlessness, and will then help to exclude red flags, such as increased shortness of breath, tachypnoea, and haemoptysis (Schroeder et al, 2011; Armstrong, 2019). SOCRATES (Table 1) is a useful method to improve comprehension of a symptom. Although primarily used in pain assessment, it can be adapted to assess a presenting respiratory symptom.

Table 1. SOCRATES

| S | Site | Ask about the location of the symptomsCan the patient point to where they are experiencing the symptom? |

| O | Onset | Clarify how and when the symptoms developed:‘When did your cough first start?’‘How long have you been experiencing the shortness of breath?’‘Was it sudden or gradual?’ |

| C | Character | Is your cough continuous or occasional?Consider the sputum characteristics – colour, amount, blood, odour |

| R | Radiation | Is the symptom moving anywhere else?Is the chest pain radiating? |

| A | Associated symptoms | Are there any other symptoms associated with the current symptom?Any chest pain or tightness?Any fever or diaphoresis?Any added sounds such as wheezing?Any haemoptysis?Any nasal congestion?Any ankle oedema? |

| T | Time/duration | How has the symptom changed over time? Has it worsened or improved? |

| E | Exacerbating/relieving factors | Ask if anything makes the symptom better or worse:‘Does anything make the shortness of breath worse?’ (exertion, exposure to an allergen, lying flat)‘Does anything make the pain better?’ (rest, inhaler, antibiotics) |

| S | Severity | Can the patient speak in full sentences?Ask about the activity limitations – how far can the patient walk? Can the patient lie flat or does it disrupt sleep? |

Following the analysis of the patient's current complaint, the practitioner should consider all other aspects of the patient's history (Table 2) which may provide clues to the patient's diagnosis. Relevant past medical history would include asthma, COPD, lung cancer, thoracic surgery or trauma, any hospitalisations for pulmonary disorders, any use of oxygen or ventilation assisted devices such as continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or bi-level positive airway pressure (BiPAP) machines.

Table 2. Patient history

| Past medical history | Any previous operations or proceduresAny use of oxygen or continuous/bi-level positive airway pressure devices (BiPAP or CPAP)Any chronic disorders such as asthma, COPD, cystic fibrosis |

| Drug history | Prescribed drugs, over the counter drugs, recreational drugs, herbal remedies, include allergies |

| Family history | Tuberculosis, cystic fibrosis, emphysema, allergies, asthma, bronchiectasis, clotting disorders (risk of pulmonary embolism) |

| Social history | Smoking, alcohol, consider diet and lifestyle, occupational history, travel history, sexual history |

| Systematic enquiry | Run through common symptoms of all the systems |

Common presentations and differential diagnosis

One of the most common presenting respiratory symptoms is coughing, which could be related to either localised or general irritation in the respiratory tract (Smith and Woodcock, 2016; Ball et al, 2019; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE], 2021). Coughing is usually a reflexive response and can have a range of causes such as an irritant, an inflammatory process such as asthma, an infection, or a mass compressing part of the bronchial tree. Retrieving a thorough background of the nature of the cough will help aid a diagnosis. For example, a cough accompanied by mucous could indicate an infection or an exacerbation of asthma, whereas a dry, non-productive cough could indicate cardiac problems or an allergen. A new continuous cough may also be an indication of the highly contagious coronovirus-19 (COVID-19), so it is important to check vaccination history and ensure a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test has been obtained (NHS, 2021).

Knowing the duration of a cough will help support diagnosis. An acute cough is defined as a cough <3 weeks in duration (Irwin et al, 2018), with the most common cause being bacterial or viral infection, so consider other clinical signs such as malaise, pyrexia, tachypnoea, and sputum production (Hill et al, 2019). A chronic cough is defined as a cough lasting more than 8 weeks and is a feature of many respiratory diseases (Table 3) (Smith and Woodcock, 2016; NICE, 2021).

Table 3. Causes of chronic cough

| Cause | Further information |

|---|---|

| Bronchiectasis | Daily sputum production, progressive breathlessness, haemoptysis, non-pleuritic chest pain, and coarse crackles in early inspiration in the lower lung fields |

| Bronchitis | Can be acute or chronic: cough with or without sputum, breathlessness, wheeze or general malaise |

| Cystic fibrosis | Persistent moist cough and gastrointestinal symptoms are often present from birth, finger clubbing, and failure to thrive in children |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Persistent progressive breathlessness usually associated with wheezing or chest tightness, hyperinflated chest, possibly with signs of right-sided heart failure such as ankle oedema and increased jugular venous pressure |

| Cough variant asthma | Wheeze, breathlessness, worsening symptoms at night, in the morning, or with exercise and exposure to allergens. Reduced peak flow |

| Foreign body aspiration | Sudden-onset cough, stridor (upper airway) or reduced chest wall movement on the affected side, bronchial breathing, and reduced or diminished breath sounds (lower airway) |

| Heart failure | Orthopnoea, oedema, a history of ischaemic heart disease, and fine lung crepitation |

| Interstitial lung disease | Asbestosis, pneumoconiosis, fibrosing alveolitis, sarcoidosis – clinical features include a dry cough and fine lung crepitations |

| Lung cancer | Persistent cough, haemoptysis, weight loss or persistent hoarse voice |

| Obstructive sleep apnoea | Cough associated with daytime fatigue, obesity, jaw abnormalities |

| Pertussis | Paroxysmal cough, catarrh lasting 1–2 weeks, malaise, low-grade fever, dry unproductive cough, coughing fits followed by an inspiratory gasp (whooping sound) |

| Pulmonary tuberculosis | Persistent productive cough, which may be associated with breathlessness and haemoptysis |

| Pulmonary embolism | Acute-onset breathlessness, pleuritic pain, haemoptysis, crackles, and sinus tachycardia |

When examining a patient with the production of sputum, getting an insight into the amount and colour will support your diagnosis. For example, green, purulent sputum would indicate an infection, whereas haemoptysis could indicate cancer, a pulmonary embolism (PE), or an infarction (Ball et al, 2019).

Red flags

A red flag is a sign or symptom that alerts us to the possible presence of a serious or life-threatening condition. Red flags must be considered when a patient presents with a group of symptoms that need urgent or immediate further action (Table 4) (Lowth, 2016). In primary care, patients often present with non-specific symptoms and differentiating between innocent symptoms and a serious disease can be challenging. Unnecessary referrals and diagnostic testing need to be balanced against the risk of missing a diagnosis; therefore, the red flag concept is of immense value in facing this challenge (Ramanayake and Basnayake, 2018).

Table 4. Red flags

|

Clinical examination

Following a detailed history taking, a clinical examination should be conducted using a systematic assessment tool such as IPPA (Inspection, Palpation, Percussion and Auscultation) (Proctor and Rickards, 2020).

Inspection

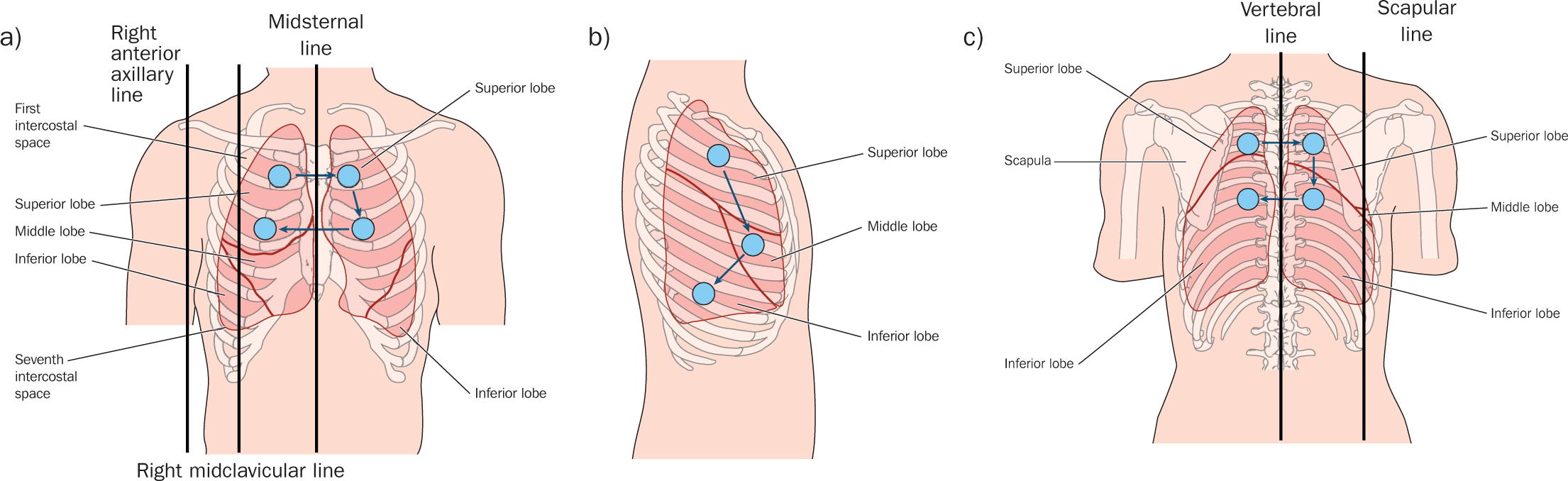

During inspection, where possible ask the patient to remove clothing to the waist, offering a drape or sheet for dignity and comfort. It is important to be aware of anatomic landmarks of the chest (Figure 1). Consent must always be obtained and a chaperone offered before continuing with the inspection.

Figure 1. Thoracic landmarks. a) Anterior thorax; b) right lateral thorax; c) posterior thorax

Figure 1. Thoracic landmarks. a) Anterior thorax; b) right lateral thorax; c) posterior thorax

Initiate the inspection with an overall assessment of the patient's colour, taking note of any scars, bruising or chest deformities such as kyphosis, scoliosis, pectus carinatum or pectus excavatum. A barrel chest is the result of compromised respiration such as chronic asthma, emphysema, or cystic fibrosis (Ball et al, 2019). In babies and young children, an asymmetric chest movement is seen in the presence of diaphragmatic hernias, cardiac lesions and pneumothorax (Jevon et al, 2019).

Hands

Consider the hands for signs of peripheral cyanosis, tar staining, palmar erythema, bruising, and dilated veins (Jevon et al, 2019). Clubbing is focal enlargement of the connective tissue in the terminal phalanges of the digits (Figure 2) and is confirmed by a positive Schamroth sign (McGee, 2017). Clubbing is associated with respiratory disorders such as lung tumours and bronchiectasis, and occasionally seen in endocarditis and heart disease (McGee, 2017). Fine tremors could be induced by beta-2 agonist therapy, while asterixis, characterised by irregular, flapping motions of the hands could be indicative of CO2 retention.

Figure 2. Clubbing of the fingers

Figure 2. Clubbing of the fingers

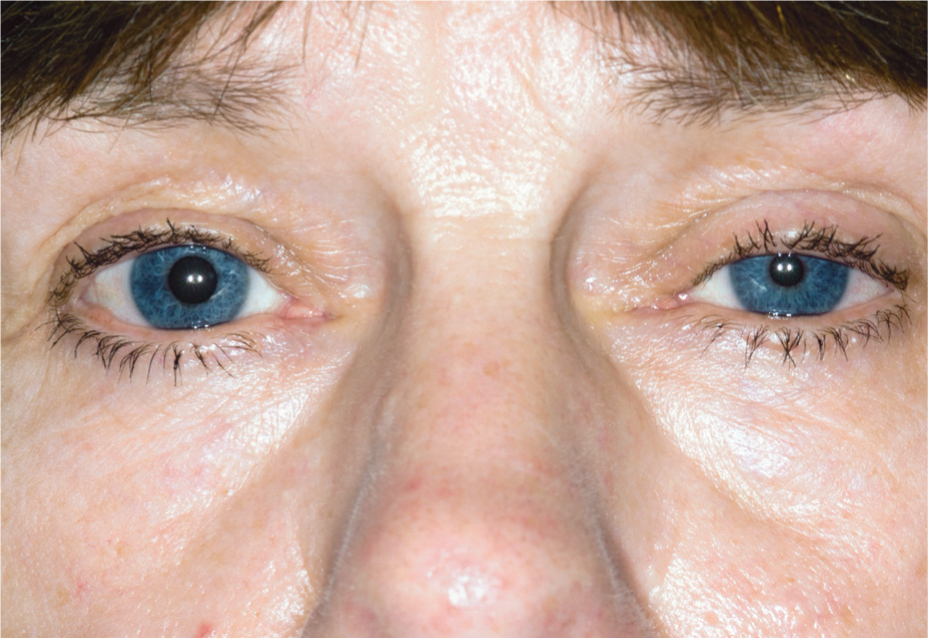

Observe the patient's face for pallor, central cyanosis, or asymmetry. Ptosis, miosis and enophthalmos are all features of Horner's syndrome (Figure 3) and could suggest cancer in the apex of the lung (Pancoast tumour) (Malem, 2017).

Figure 3. Horner's syndrome suggestive of Pancoast tumour

Figure 3. Horner's syndrome suggestive of Pancoast tumour

Palpation

Following a thorough inspection, palpate the thorax to assess for chest wall tenderness or masses, pleural friction or rubs, bronchial and tactile fremitus (McGee, 2017). Tactile fremitus is the vibration felt by resting the palmar surface of each hand on the chest simultaneously and symmetrically and asking the patient to repeat the words ‘ninety-nine’ (McGee, 2017; Ball et al, 2019; Potter, 2021). Decreased or absent vibration over an area suggests the presence of fluid or air outside the lung, for example a pneumothorax or a pleural effusion. Increased vibration, however, indicates increased tissue density due to consolidation, lobar collapse, or a tumour (Potter, 2021). Finally, check for chest expansion by bringing thumbs together at the patient's midline and asking the patient to breathe in.

Percussion

Percussing the chest involves placing one finger firmly against the chest wall and striking it with the index and middle finger of the opposite hand. The volume and pitch indicate a change in the consistency of the underlying tissue (Table 5) (Fraser, 2018).

Table 5. Percussion tones heard over the chest

| Type of tone | Intensity | Pitch | Duration | Quality | Indications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resonant | Loud | Low | Long | Hollow | Normal lung tissue |

| Flat | Soft | High | Short | Very dull | Solid area such as muscle or bone |

| Dull | Medium | Medium to high | Medium | Dull thud | Fluid filled areas such as pneumonia, atelectasis, or pleural effusion. Liver or cardiac area |

| Tympanic | Loud | High | Medium | Drum like | Normally heard over areas with excessive air such as pneumothorax or stomach |

| Hyper-resonant | Very loud | Very loud | Long | Booming | Heard over hyper-inflated areas such as pneumothorax, asthma, or emphysema |

When percussing the patient's chest, compare all areas bilaterally, using one side as a control for the other.

Auscultation

Auscultation of the chest provides important information about the condition of the lungs and pleura. The optimal position of the patient is sitting in a chair or on the side of a bed, however the patient's clinical condition and comfort must be considered first. Breath sounds are produced from the flow of air through the bronchial tree and can be vesicular, bronchovesicular or bronchial/tracheal. Breath sounds will be louder and courser in babies than in adults due to less subcutaneous tissue to muffle the sound transmission (Fraser, 2018). The most common sounds heard on auscultation are crackles, wheezes, rhonchi, and friction rub (Table 6). Crackles are often heard during inspiration and may be fine, high-pitched or coarse and low-pitched sounds, which, unlike rhonchi, are discontinuous and not cleared on coughing (Ball et al, 2019). In contrast, a wheeze is a high-pitched sound indicating a narrowed or obstructed airway. A bilateral wheeze is often caused by asthma bronchospasm or bronchitis; however, a unilateral wheeze is suggestive of a foreign body or a tumour compressing part of the bronchial tree (Ball et al, 2019).

Table 6. Adventitious breath sounds

| Sound | Quality | Cause | Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crackles (rales) | Short, popping, discontinuousFine: wood burning in a fireplaceCoarse: lower pitch, longer | Air being forced through airways narrow with mucus, pus, fluid; opening of deflated alveoli | InfectionInflammationCongestive heart failure |

| Wheezes | High-pitched musical soundsThrough both inspiration/ expiration | Airway constriction | AsthmaCOPD and bronchitis |

| Rhonchi | Lower-pitched than wheezes‘Snoring’ qualityLoudest during expiration | Usually due to secretions in large airwaysClears with cough | BronchitisPneumonia |

| Friction rub | Deep, harsh, gratingPrimarily inspiration | Friction of inflamed pleural surfaces rubbing together | Pleuritis or pneumonia |

Investigations

Since multiple conditions may produce similar signs and symptoms, other investigations may be required to confirm or refute a diagnosis.

Check the patient's oxygen saturation along with other vital signs including temperature, respiratory rate, and blood pressure (Table 7). If a patient presents with a productive cough, then a sputum sample would help determine if a micro-organism is present and the specific antibiotics required. This would assist in reducing antibiotic resistance through prescribing the most appropriate antibiotics for the micro-organism or not for those who do not have an infection (Blakeborough and Watson, 2019).

Table 7. Further investigations

| Oxygen saturations | Be aware of patient's normal and respiratory history |

| Vital signs | Respiratory rate, temperature, blood pressure, heart rate |

| Sputum sample | Confirm or refute whether an infection is present and whether antibiotics are required |

| Peak flow | In asthmatics, consider the patient's normal |

| Spirometry | If the patient has a persistent cough or shortness of breath to help diagnose asthma, COPD, cystic fibrosis or pulmonary fibrosis |

| Chest X-ray | If abnormalities found on examination |

| A cardiovascular examination | If it is possibly a cardiac condition |

| ECG | If considering a cardiac cause |

| Blood tests | Full blood count, urea and electrolytes, liver function tests, coagulation |

Conclusion

Respiratory complaints are very common in primary care with many different conditions offering similar signs and symptoms. Advanced practitioners working in primary care therefore have an important role in adequately assessing and examining patients. A thorough history taking, and systematic assessment is vital to determine the cause of the respiratory symptoms which may not always be respiratory in origin. The protection of the patient and public safety is paramount, therefore any concerns must be appropriately referred and advice sought if the situation is beyond the levels of the advanced practitioner's competence.

KEY POINTS:

- Taking a patient history is an essential element in establishing a diagnosis and is used to get a deeper understanding of the patient's symptoms

- Don't decide on your diagnosis too early

- Listen to your patient

- Follow a systematic assessment tool for clinical examination such as Inspection, Palpation, Percussion and Auscultation (IPPA)

CPD REFLECTIVE PRACTICE:

- What is the purpose of obtaining a systematic health history?

- What red flags do you need to consider when assessing a patient with respiratory symptoms?

- Which investigations may be needed in a patient presenting with respiratory symptoms?