Promoting health and wellbeing is a fundamental part of every nurse's role (Nursing Midwifery Council, 2018). Practice nurses are ideally placed within local communities to have a significant impact on addressing health inequities (Heaslip and Nadaf, 2019). However, to achieve this they need to understand the many factors that lead to certain groups having poorer health outcomes. This, the first of two articles, begins by exploring both health and access to UK health services. It then examines the equality philosophy at the core of the NHS, before distinguishing between inequality, inequity and related concepts when poorer health outcomes are examined. This article then continues to present some key governmental and professional papers driving healthcare policy. The follow-up article then explores health experiences of certain communities, such as ethnic minorities, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer (LGBTQ+) and individuals experiencing homelessness, as well as the role of practice nurses in addressing their health experiences.

Health and wellbeing in the UK

The UK has an ageing population; with life expectancy at birth of around 79 years for men and 83 years for women (Office for National Statistics (ONS), 2021a). A demographic trajectory also influenced by a significant reduction in infant and child mortality, with the former the lowest on record in 2019 (ONS, 2021b). Advances in longevity do not automatically match advances in health and wellbeing across all social groups. For example, the UK is the 22nd richest country in the world (based on gross domestic product per capita (International Monetary Fund, 2021), yet it has huge variations of wealth. The UK (UK Parliament, 2021) defines poverty in two ways; relative low income (living in a household with income below 60% of the national median that year) and absolute (living in household with income below 60% of the inflation adjusted median of a base year - usually 2010/11). The most recent data set (2019/20) identifies that there were 14.5 million (22% of the population) and 4.3 million children (31%) living in relative low income after housing costs were deducted, and 11.7 million people living in absolute low income after housing costs were deducted (UK Parliament, 2021). A trend likely to have increased when the health and economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is considered. Poverty is important as there is a negative cycle between poverty and health (British Medical Association, 2017). Indeed, the World Health Organization (2021a) argues that poverty is the single largest determinate of health, as poorer people have shorter lives and greater health and wellbeing challenges. In the UK, someone living in a deprived area of England is more likely to die eight and a half years younger than someone living in a more affluent area (ONS, 2021a). They will also experience more ill health and reduced wellbeing when compared to their wealthier social groups. In addition to poverty, health inequality is also monitored by geography, by specific characteristic such as sex, ethnicity, disability or by belonging to a socially excluded group (The King's Fund, 2020). We need to ask ourselves, why this is happening and how can it be prevented?

Access to healthcare in the UK

The NHS is free at the point of use, as set out in the seven principles of the NHS: these include providing a service based on need and not a person's ability to pay, as well as providing a comprehensive service to all regardless of race, disability, age, or gender (Department of Health and Social Care, 2021). However, there are still a wide number of people who struggle to access services or become disengaged for various reasons. For some, they feel discriminated against, due to race, age or sexual orientation. For others, the ability to afford appointments becomes prohibitive due to travel costs and lost time and wages. Literacy can also be an issue, with people not always being able to read, easily understand and utilise information conveyed within their lived experience (NHS, 2021a).

Differences between (in)equality and (in)equity and other key terms

The King's Fund (2020) recognise that the term health inequality can have multiple meanings including differences in people's health, differences in care they receive and the opportunities they have to live healthy lives. The key areas that are linked to inequality identified by the King's Fund (2020) are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Key areas linked to health inequality

| 1. Health status, such as life expectancy and prevalence of health conditions |

| 2. Access to care |

| 3. Quality and experience of care |

| 4. Behavioural risks factors |

| 5. Wider determinants of health |

Inequalities in access to health services are preventable; those who are disadvantaged and difficult to reach are more likely to experience health inequalities and are more likely to have poor health outcomes (Hui et al, 2020). An insightful depiction of how fundamental causes and wider environmental influences can affect health inequality was created using a train station tube map showing differences in children's life expectancy in stations that are only minutes apart; for example, life expectancy of 96.4 years for those born near Oxford Circus while children born around Star Lane have a predicted life expectancy of 75.3 years (Cheshire, 2012). The fundamental differences between these tube stops are access barriers and lifestyle risks.

Within healthcare, the terms (in)equality and (in)equity are often used interchangeably, yet there is a nuanced difference needed to understand how groups of people in society access and experience healthcare. According to Global Health Europe (2009), inequality is denoted as not having sameness and is described as the uneven distribution of health or healthcare resources. Inequity is denoted as unfairness and is described as people not being able to access the same healthcare opportunities because of corruption, poor governance, and cultural disparities. In terms of healthcare, Table 2 presents a definition of key terms including health equity, health inequality, health inequities and health disparities.

Table 2. Defining health inequalities and inequities

| Health inequalities | Differences that exist between groups in health service access, health status and outcomes—sometimes inequalities are acceptable, for example breast screening programmes for men and women are not equal |

| Health equity | Achieving equity requires the provision of different attention to groups adversely affected so equality in access, status and outcomes can be achieved |

| Health inequities | Underpinned by social justice, health inequities refer to the unjust or unfair differences in health access, status and outcomes that exist between groups of people |

| Health disparities | Absolute and relative differences in health status and outcomes between groups and is used to provide evidence of health inequities. For instance, differences in access to determinants of health and health services and quality of health care |

Marmot review

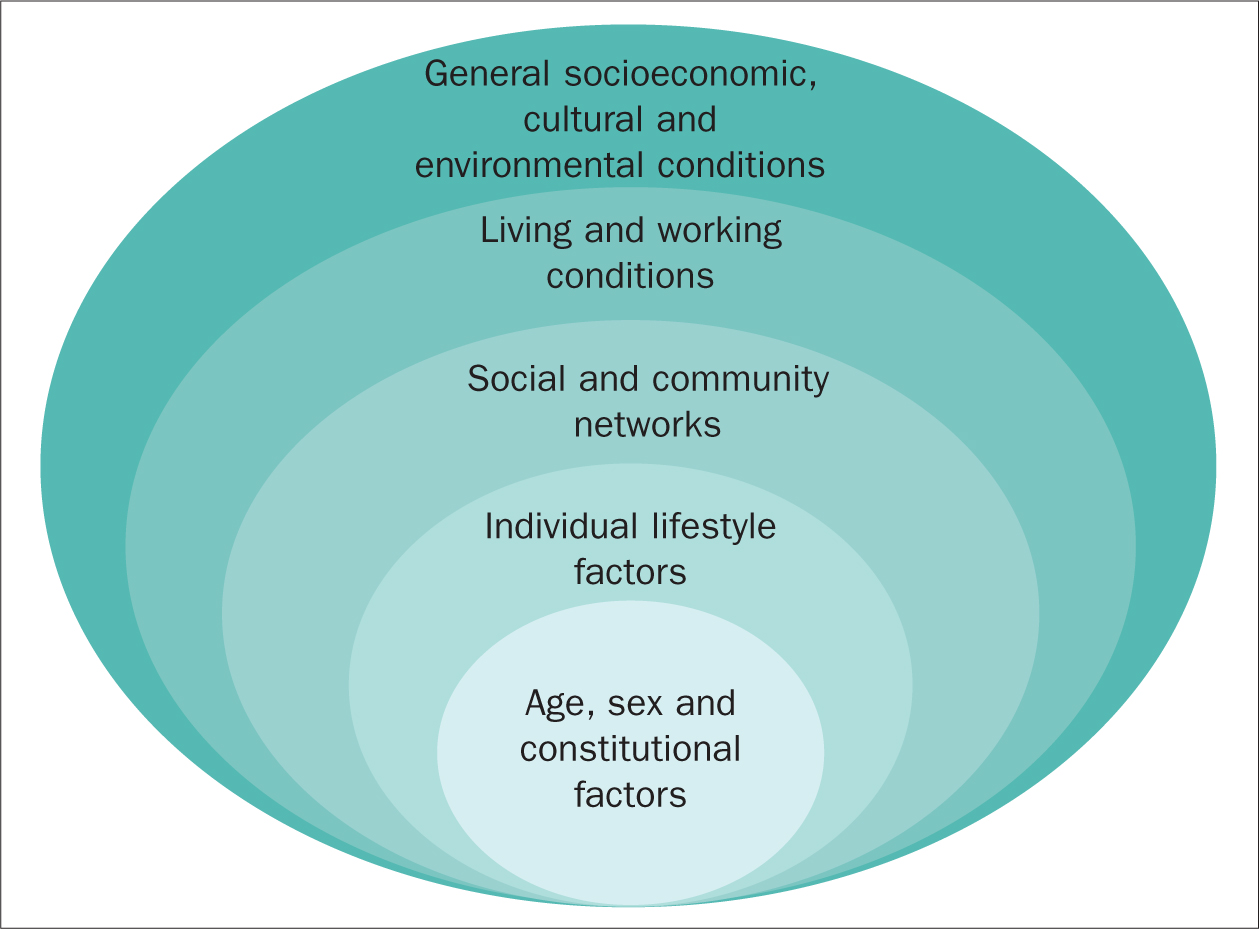

In 2008, Professor Michael Marmot was asked to chair an independent review to identify effective evidence-based strategies to address health inequalities in England with the findings published in 2010 (Marmot et al, 2010). The report identified a social gradient in health, that is, the lower an individual's social position in society then the worse their health experience/outcomes, and, conversely, the higher their social position the better their health. Marmot et al (2010) argued that social policy and actions should focus on addressing this social gradient, calling for a multi-agency approach recognising the wider social determinates of health. There are numerous modes exploring the wider social determinates of health, however the most commonly used is that of Dahlgren and Whitehead 1991 (Public Health England, 2017) (see Figure 1). As part of the holistic assessment nurses should be considering these wider bio-psycho-social factors as part of their role in health improvement and promotion. Marmot et al (2010) argued against focussing solely on those experiencing disadvantage, but advocated those actions to address the social gradient needed to be universal (ie, equality) but the scale and intensity of action had to reflect the levels of disadvantage (equity).

Despite widespread agreement and recognition of the need to implement the recommendations of the review at the time, a subsequent report (Marmot et al, 2020) examining progress 10 years on identified that since 2010 there has been a widening of health inequalities in England, most notably for women. Although for both men and women, the perpetuation of the social gradient continues to correlate with the fact that those living in more deprived areas spend more of their shorter lives living in poor health. Given what we have since experienced with the COVID-19 pandemic, then these costs may be even higher and more complex.

Strategic healthcare priorities for 2020 and beyond

Working within a global economy with limited healthcare resources, it is imperative to be able to deliver equal and equitable care to everyone as a 20th century strategic priority. The 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were introduced as an urgent call for all countries to address poverty and other deprivations (United Nations, 2015). Of particular interest to practice nurses are SDG 1 (no poverty), SDG 3 (good health and well-being), SDG 5 (gender equality) and SDG 10 (reduce inequalities). Of particular note are two recent challenges to the continued implementation of good health and wellbeing (SDG 3 and SDG 10): the recent COVID-19 pandemic which has highlighted health inequities faced by ethnic minority groups in particular (we shall address this in the next article); and the international shortage of nurses. The most recent report from the World Health Organization (2021b) focuses on ‘Gender and Health’, recognising that healthcare access experiences can be directly linked to gender due to rigid gender norms, violence, stigma and discrimination, and poverty. While we often think these issues are related to low income countries, there is evidence of gender differences in the UK, especially in terms of period poverty (young girls missing education due to lack of finances to purchase sanitary products) and socially excluded groups, such as people who are homeless and ethnic minority groups, which we explore further in the next article in the series.

In the UK itself, the 2010 Equality Act confirmed a duty to non-discriminatory practice and the NHS and staff working within it as a public sector provider of care have specific duties under the Public Sector Equality Duty (Equality and Human Rights Commission, 2021) to provide equal opportunities in every community, eliminate discrimination and victimisation and foster open and honest communication about equitable and equal access to healthcare (Government Equalities Office, 2015). In 2018, NHS England published its response to the specific equality duties of the Equality Act and identified 6 objectives (Table 3) to which all who work in the NHS (including practice nurses) have a responsibility to deliver.

Table 3. NHS England response to the specific equality duties of the Equality Act 2010

| Equality objective 1 | To improve the capability of NHS England's commissioners, policy staff and others to understand and address the legal obligations under the public sector Equality Duty and duties to reduce health inequalities introduced by the Health and Social Care Act 2012 |

| Equality objective 2 | To improve disabled staff representation, treatment and experience in the NHS and their employment opportunities within the NHS |

| Equality objective 3 | To improve the experience of LGBT patients and improve LGBT staff representation |

| Equality objective 4 | To reduce language barriers experienced by individuals and specific groups of people who engage with the NHS with specific reference to identifying how to address issues in relation to health inequalities and patient safety |

| Equality objective 5 | To improve the mapping, quality and extent of equality information in order to better facilitate compliance with the public sector Equality Duty in relation to patients, service-users and service delivery |

| Equality objective 6 | To improve the recruitment, retention, progression, development and experience of the people employed by NHS England to enable the organisation to become an inclusive employer of choice |

This commitment reflects the recognition by the NHS and Public Health England (2017) that health inequalities are unfair and preventable. It also recognises the nurse's advocacy and enabling role, and the need to move beyond direct patient care to also become involved in cultural and structural change and consciousness raising. The NHS Long-Term Plan (NHS, 2021b) sets out measurable goals for reducing health inequalities, by targeting a greater share of funding to areas with higher health inequalities. These areas in turn have to clearly define how this additional funding will be used to reduce health inequalities and address risk factors of smoking, poor diet, high blood pressure, obesity, and alcohol and drugs, all of which cause the most premature deaths in the UK (NHS, 2021b), all of which we argue are within the key domain of practice nurses.

Conclusion

While the current focus of the NHS is on equality, it is evident that there are important nuances to consider. For example, there is a lack of equity in health services, which leads to health disparities for people living in the UK linked to the wider determinates of health. Practice nurses are ideally placed to address some of these wider determinates as part of their holistic assessment and in meeting the Public Sector Equality Duties. Our next article shall build on this to explore health inequity of three particular communities including people who are homeless and individuals from LGBTQ+ and ethnic minority communities, as well as how practice nurses can work to address the health inequities and disparities these groups face.

KEY POINTS

- Understanding key terms such as health equality, equity and disparities is important for practice nurses in order to be able to critically consider the health experiences of people they work with

- In the holistic assessment of patients, it is fundamental that practice nurses reflect and consider how the wider determinates of health impact on the health and wellbeing of their patients

- While the NHS is committed to equality, practice nurses need to understand how this could inadvertently lead to inequity unless they tailor interventions to meet individual needs

CPD reflective practice

- Think about the terms equality, equity and health disparities. Does the practice where you work focus on equality or equity? What are the implications of this in terms of health disparities?

- Identify one patient you work with, considering the wider determinates of health, what issues do you think influences their health decisions or access?

- Identify one aspect of practice that you could implement which would help address health disparities

- What is your practice surgery doing to help address the UN Sustainable Development Goals?