1.0 Introduction

1.1 Background

The Core Supervision Training Module is funded by NHS England and is being implemented in general practice (primary care) as part of the Learning Environments Assessment and Placements (LEAP) Strategy 2021-2022 programme for Yorkshire and the Humber regions. The project is focussing on securing sufficient supervision capacity and foster confidence to deliver ongoing supervision activities within primary care settings to a multi-professional health care practitioner.

This is in line with the NHS People Plan (NHS England 2020) which recognises that those people working within healthcare have been and still are working under significant pressure, and that effective well-being and positive work cultures are essential if services are to be transformed successfully (NHS England, 2020).

This is reinforced by the Health and Social Care Act Regulations (2014) including regulation 18, which recognises the multiple benefits of effective supervision for the supervisor, supervisee, and organisation. Additionally, the Care Quality Commission (CQC) strongly advises supervision as it helps staff to manage personal and professional demands created by the nature of their work. There is a risk that can result in regulatory action and refuse registration for noncompliance (CQC 2023).

Core supervision has been defined as a formal process of professional support which should be viewed as a means of encouraging self-assessment, analytical and reflective skills, and can both enable and support those in clinical practice (NHS England 2022; Hussein 2023). It has been grounded in the recognition of the importance of ongoing support, professional development, and quality improvement within the healthcare sector.

In practice it provides an environment in which healthcare practitioners can explore their own personal, professional, and emotional reactions to their work. This was accomplished through a reflective process with a trained facilitator or supervisor and offers a safe place to explore aspects of clinical practice in a non-judgmental, congruent, empathetic, and confidential manner (Rogers 1961).

It differs from the clinical, educational, and managerial supervision features, by focussing and evolving growth around self-awareness and emotional intelligence with developing tools to self-support and their peers (Wallbank and Hatton 2011).

As core supervision training has been invested within the respective ICBs for the last 18 months and ongoing, there has been only informal evaluation as to its impact and embedment within general practice.

Recent systematically reviews (Rothwell, 2021; Snowden et al. 2017) have offered comprehensive insights as to what are the benefits/enablers and challenges/barriers as to why supervision processes are successful or not in a variety of clinical settings. However, there is limited focus on primary care due to its disparate workforce and siloed organisation operation (Smith 2020).

Therefore, with reference to the LEAP strategy it was considered crucial to consider whether the core supervision model had been successfully embedded into general practice and what the barriers/challenges and benefits and enablers supervisors have experienced, to evaluate learning outcomes and course content and what future training needs are required for sustainability and supporting retention of staff.

1.2 Aim and objectives

The main aim was to determine the benefits/enablers and barriers/challenges that practitioners found in implementing and embedding core supervision within their general practice.

The key objectives were to identify what the contributing factors or perspectives that prevent or enhance embedding core supervision in general practice and to understand the impact of training on a multi professional workforce in primary care and revise any resource to strengthen course content for future delivery.

2.0 Methodology and methods

An on-line Jisc survey (2019) which permitted the capture of information from a cohort of primary care practitioners who have already engaged in the core supervision model training online, from an accredited and registered nurse practitioner.

The online survey tool was chosen as many of the participants would have used this prior to the project to evaluate their learning from the core supervision training. Therefore, the survey tool would be familiar and easy to use; is General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) compliant; can uphold confidentiality; anonymise the responses, and allows the consent form to be embedded within the survey format.

2.1 Ethical approval

The study received ethical approval from Coventry University, Project Reference Number: P162553

2.2. Recruitment

This was a purposive sample which was taken across Yorkshire and the Humber encompassing three large regions including West Yorkshire Integrated Care System (ICS), South Yorkshire ICS and Humber and North Yorkshire ICS and their respective primary care networks and educational training hubs. Recruitment was based on the identified cohort variant values which were those general practice participants and teaching trainers who had completed the core supervision training.

2.3 Consent and Data Collection

The survey was sent in a confidential e-mail format and participation was stated as voluntary. This was distributed by only one of the researchers who held a contact list of the practitioners who had completed supervision training. This helped to be consistent with mailing distribution and monitor the survey uptake. Within the e-mail an attached participation information leaflet was available to read and keep as a record before accessing the embedded link to start the survey. Once the link was accessed the participant had to consent that they had read the study participation information before commencing the survey. The participant was informed that by completing the survey and pressing the ‘’complete button’’, that their responses were consenting to their data being used for the project. This was explained in the participation information sheet and that they could leave the survey and close it at any time to exit.

A reminder e-mail was sent after two weeks to all participants to gently encourage those who had not completed the survey. The survey was opened for only a four-week period with only one electronic reminder after two weeks from initial contact.

Any participant wanted more information could access any of the researchers through e-mail or discuss at the established supervision drop ins that were scheduled during the four-week period of data collection.

2.4 Interview Questions

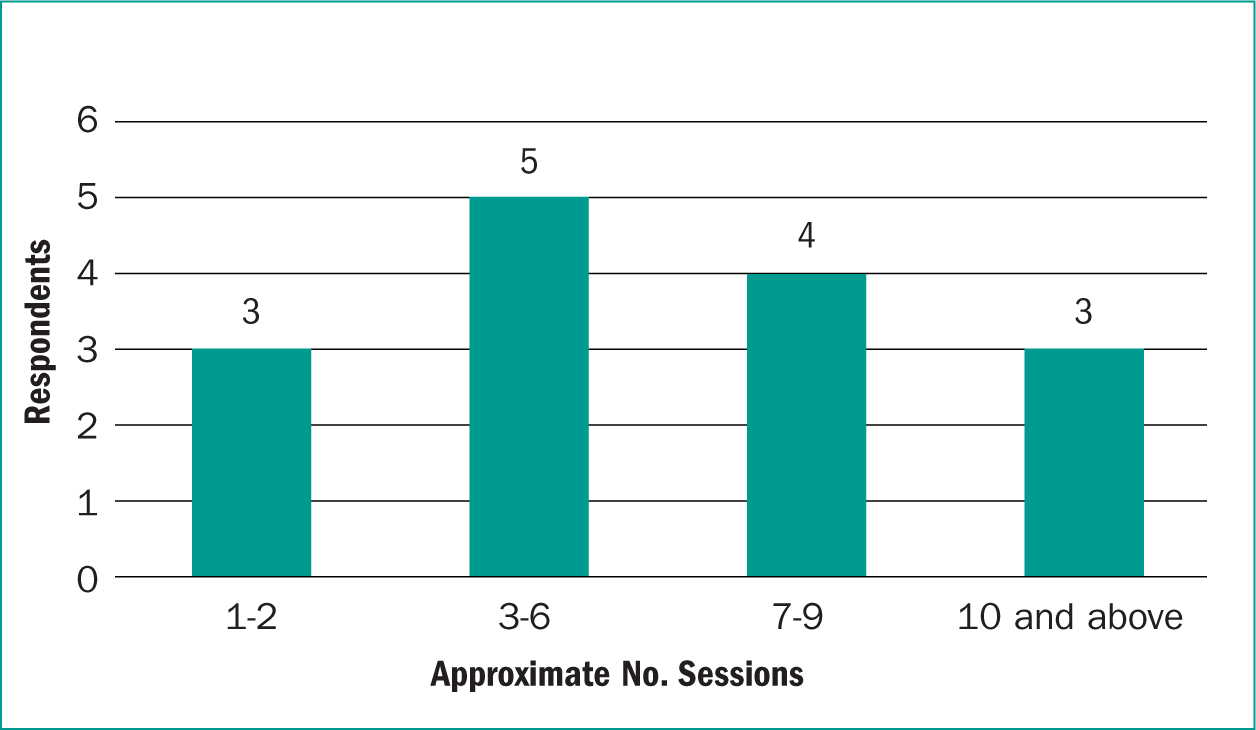

The survey consisted of twelve questions and was devised to be completed within a five-minute period to prevent any maturation or saturation around responses. The questions were either closed or of multiple choice pre-determined responses that were reflective of evidence-based findings (Rouse, 2019; Rothwell, 2021) and the participants evaluation responses and feedback from the training sessions and supervision drop ins. Three questions had a free text box for participants to add any additional information that may not have appeared in the pre-determined lists and an option for additional comments in the final question to give the participant a voice to express any further findings or concerns. The questionnaire was designed to collect data around the participants active core supervision activities or not, within their present clinical practice.

2.5 Data Analysis

All survey data was automatically numerically coded to protect the identity of participants and then exported from the Jisc survey into Microsoft EXCEL 365 Version 2304 to assist with graphic presentation and to separate any free text responses to achieve more insights in validating the data and to be aware of any potential challenges during the analytical process. In this instance the survey was used to analyse primary care practitioners' insights into key objectives to identify benefits and enablers and challenges and barriers around core supervision being implementation within practice.

Free or digital text was analysed to extract any sentiment or keywords to determine if the emotional tone of the message is positive, negative, or neutral and any further emerging themes (Marouane et al. 2021).

3.0 Results

Primary care practitioners were surveyed over three regions of Yorkshire and the Humber, from 43 identified Primary Care Networks (PCNs). The response rate over a four-week period is expressed in the Table 1.

| Primary care practitioners contacted | Respondents | Response Rate |

|---|---|---|

| n= 123 | n=30 | 24.3% |

As this was a small sample survey with a cohort size of less than 500 a response rate between 20–25% was required to provide a substantive and confident estimate of findings (Wu et al, 2022).

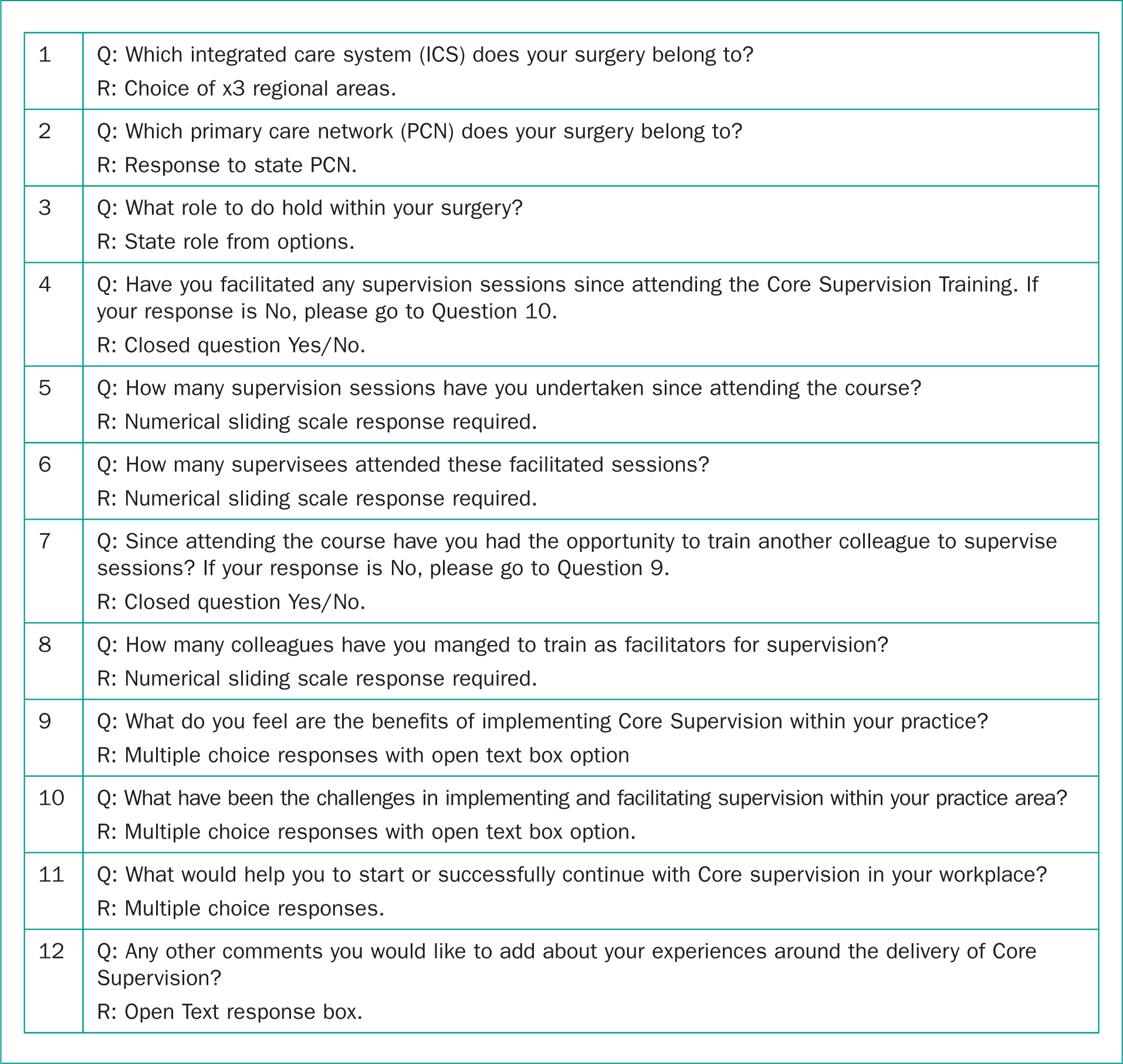

From the response of question 3, participants roles are expressed in Figure 2. The Advanced Clinical Practitioners had the highest response rate followed by those in Higher Education institutes (HEI) teaching or practising primary care.

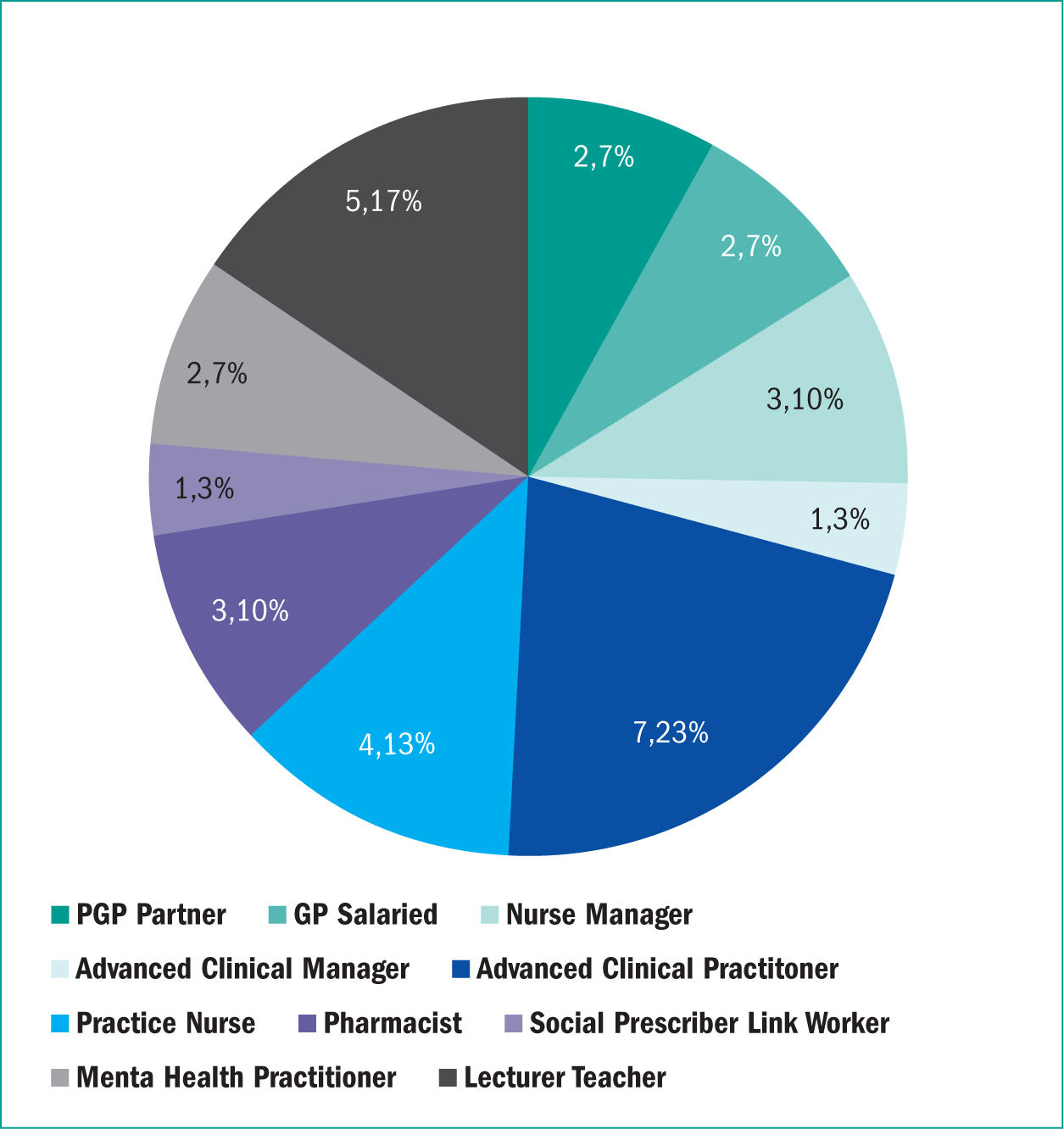

Figure 3 demonstrates that out of the thirty participants only half had managed to commence supervision sessions with their peers. This was 50% of the respondents within the survey.

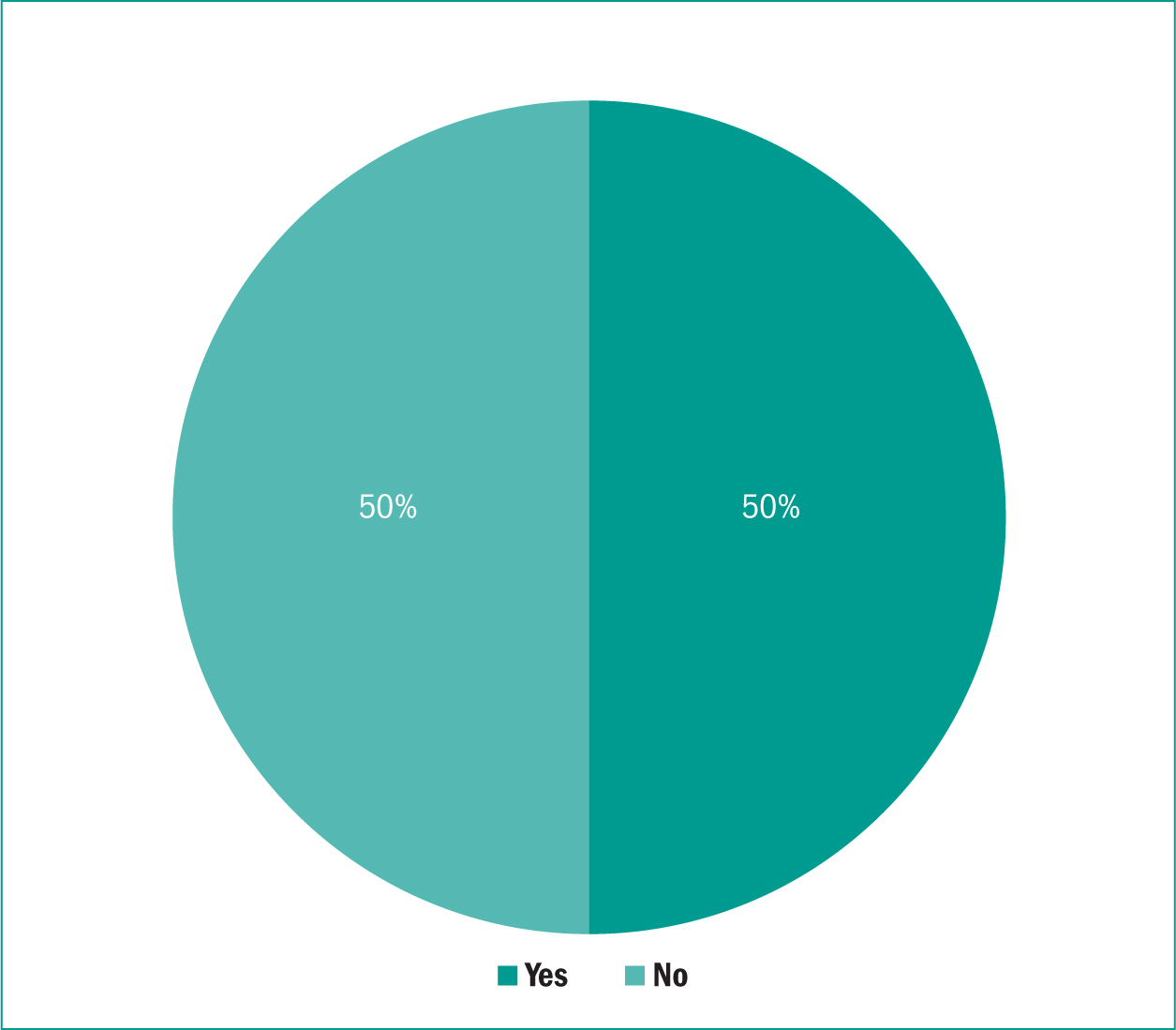

Figure 4 demonstrates that 15 participants have successfully been able to commence supervision post training. Three participants have successfully completed 10 or more sessions and three participants a minimum of two sessions. These figures could be dependent upon when the participant had completed their training within the 18-month period since the commencement of the training.

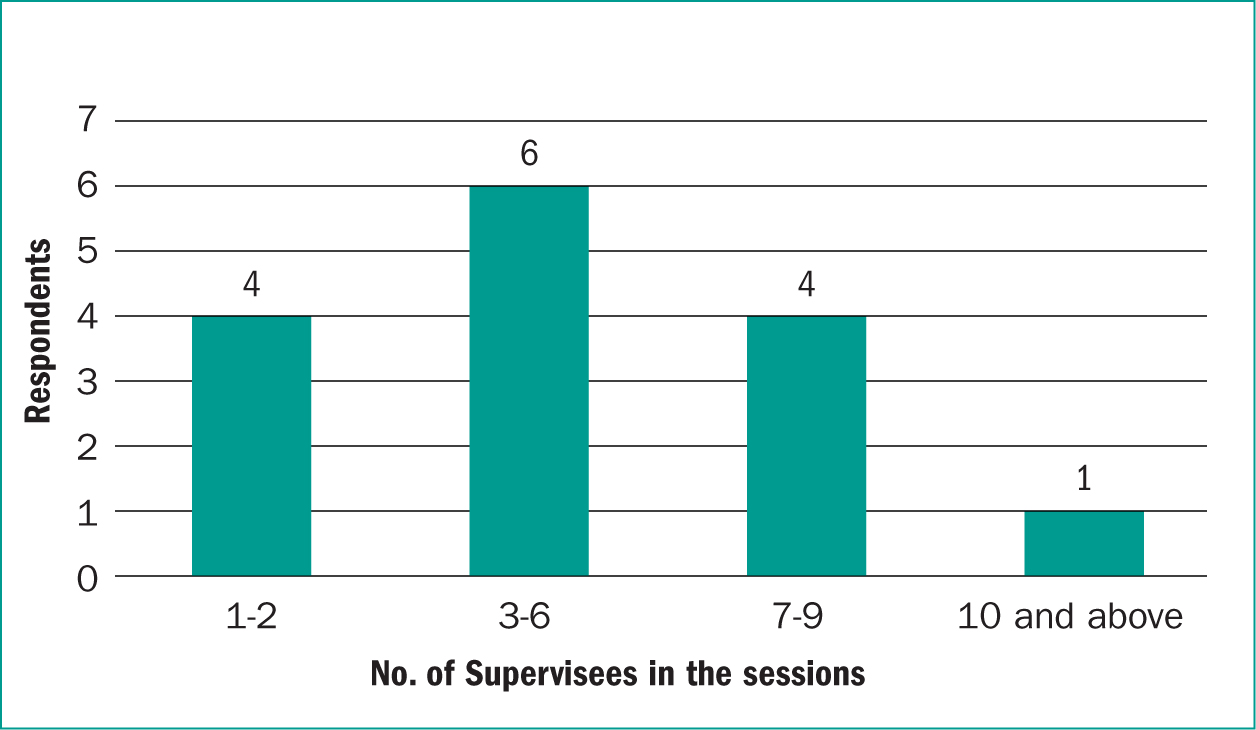

Figure 5 is representative of how many supervisees have engaged within a facilitated core supervision session and it suggests that 3 to 6 supervisees are a desirable number to accommodate core supervision.

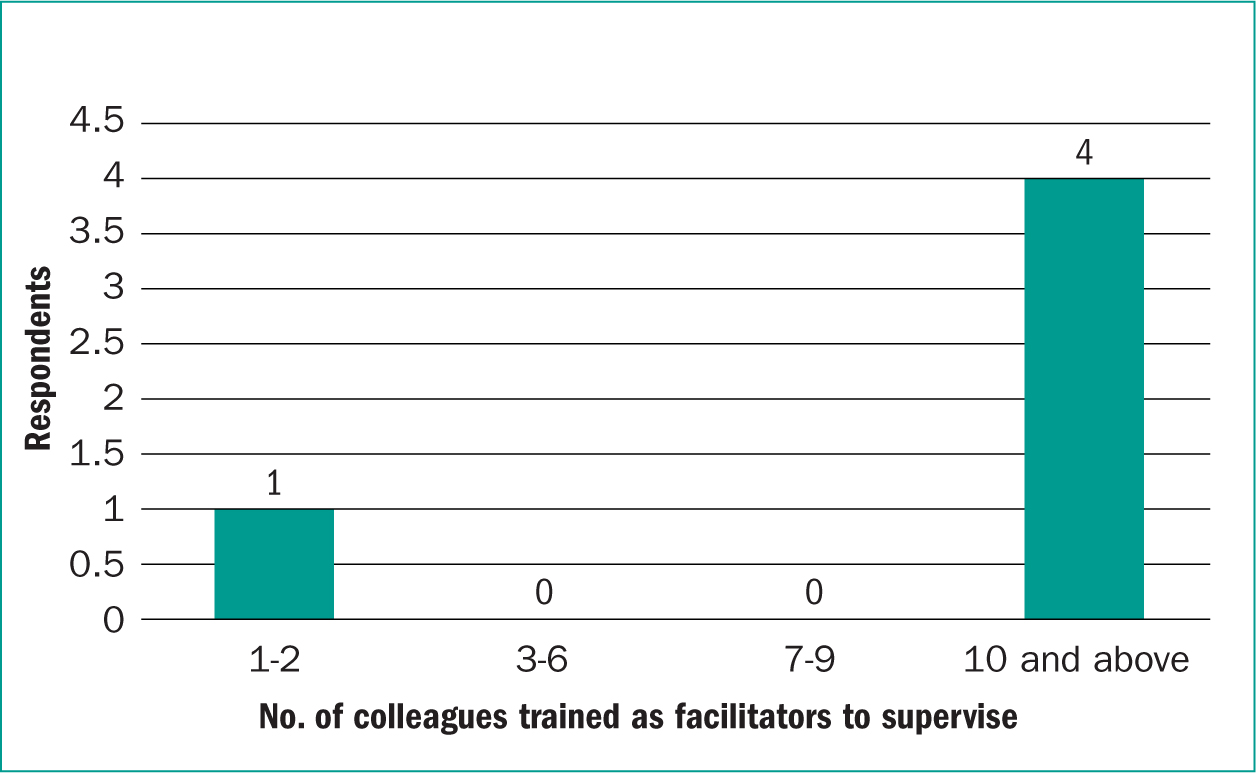

With regards to question 7, participants were asked if they had had the opportunity to train another colleague to facilitate a core supervision session. Only five participants responded who had had the opportunity to disseminate training. These participants were asked how many peers they had trained. The outcomes are represented in Figure 6. Further analysis would be required to identify what health practitioner or primary care roles were more successful in training their peers.

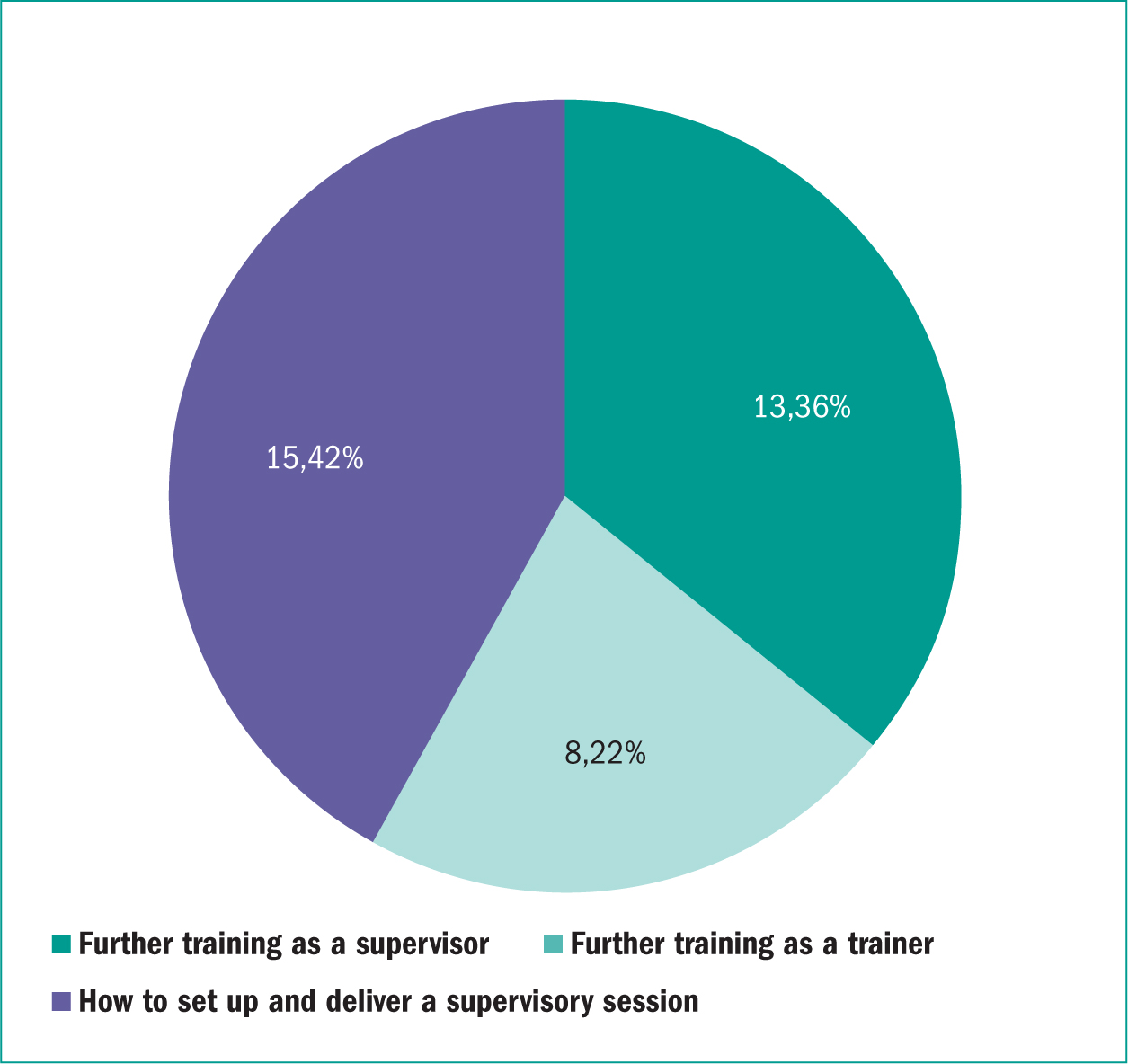

Figure 7 is representative of question 11 and states that following initial training further supervision is required how to implement successfully and deliver a supervisory session followed by further training to complement the initial course. This would indicate a structured process could be required to facilitate a group of practitioners or evolve more coaching skills from training to undertake a one-to-one session. Further training as a trainer was seen as the least priority, and further investigation would be needed to uncover whether this was confidence to disseminate training or other areas such as coaching and teaching skills.

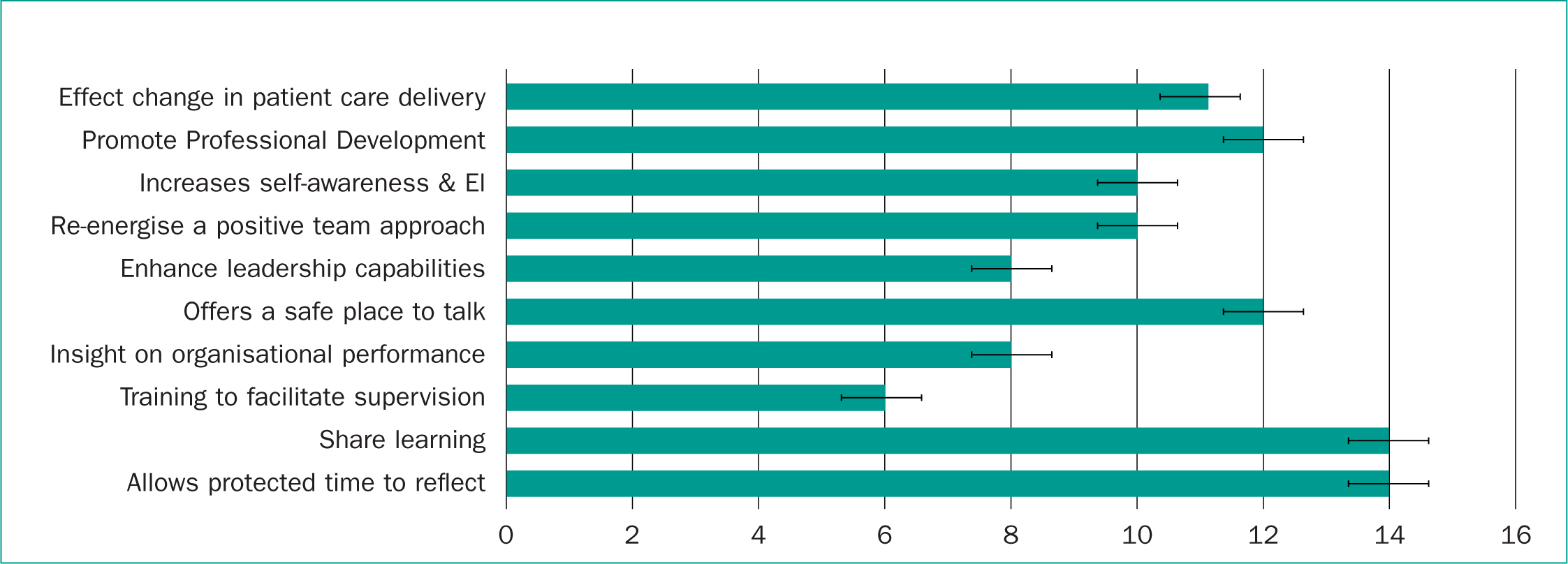

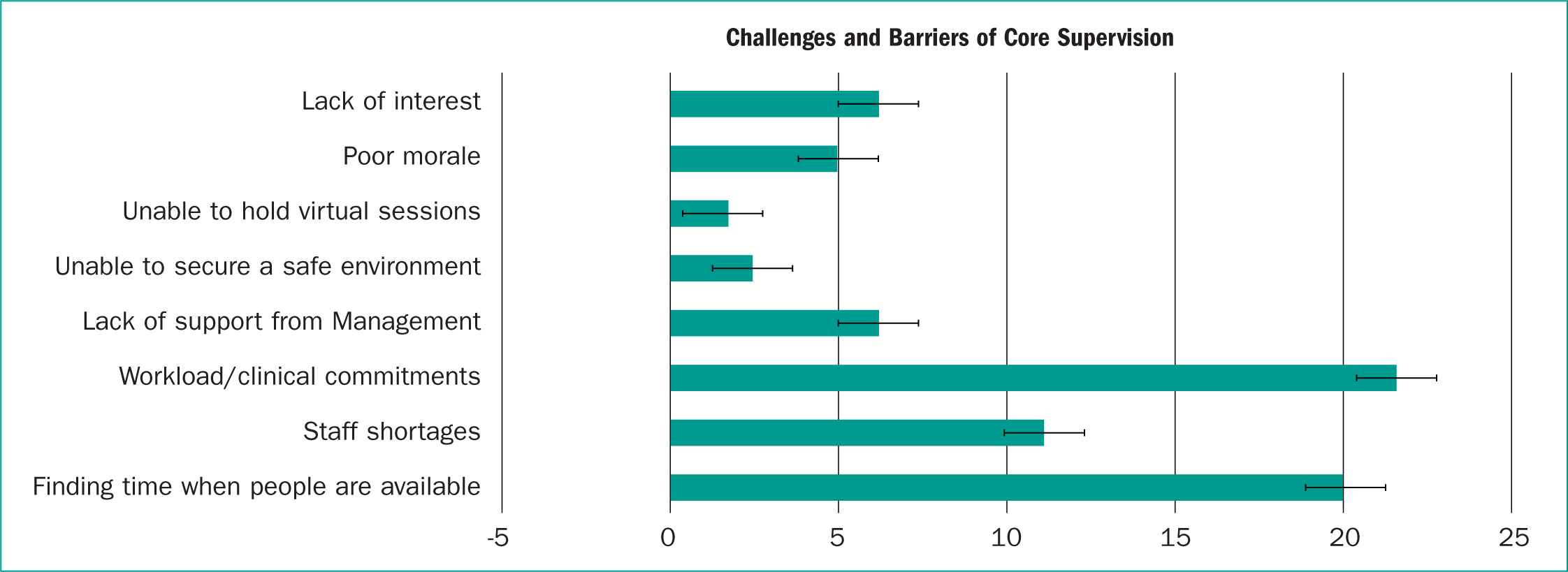

The key questions of the benefits and enablers as well as the challenges and barriers were expressed in questions 9 and 10 and the data is demonstrated in Figure 8 and 9. These questions had multiple choice responses, and the respondent could pick more than one. The indications are that sharing learning and having protected time were the key enablers in participating in core supervision and workload and clinical commitments with finding a mutual time to attend supervisions was seen as the major barriers.

Table 2 expresses the mean, variance (β2) and standard deviations (SD) of the analysed data from questions 9 and 10, which are the critical questions of the study around benefits, enablers, challenges, and barriers.

| Mean Rank | Variance o2 | Standard Deviation (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q. 9Benefits/Enablers | 5.41 | 9.23 | 3.04 |

| Q.10Challenges/Barriers | 3.23 | 4.77 | 2.18 |

The standard deviations were low indicating that there is a consistency within the data set around the questions posed and nearer to the mean. However, there were diverse patterns in question 9 data which are indicative when scenarios or multiple options around actions are offered. In contrast question 10 data had a lower variance in comparison which may be indicative that the barriers and challenges to core supervision have more consistency and accuracy.

To analyse the free text offered in questions 9, 10 and 12, a word cloud was used to visualise what the participants really felt and wanted from core supervision and what they thought about the topic of study. It offered the participant a voice beyond the designated multiple choice or closed question responses and help to contextualise the quantitative data. (See figure 10.)

4.0 Findings

4.1 Protected time and a safe space

Participants highlighted the value in being given protected time, which offered the opportunity to reflect and debate on issues with regards practice and staff wellbeing (Morgan 2014). Core supervision offers the opportunity of sharing tacit knowledge and providing feedback to confirm that staff had adhered to undertaking good clinical practice with a high-quality patient care (Brink et al., 2012). Additionally, by having an open and safe space where the supervisor and supervisees felt comfortable to trust and express concerns without prejudice and judgement was considered an integral part of core supervision process (Kutzsh et al. 2014). Participants indicated that they did not want a hierarchical approach, as this reinforces the feeling of safety within the groups as some practitioners did criticise that hierarchy structures will play a part depending on the needs of the primary care organisation rather than their professional development (McLaren et al. 2013).

4.2 Enhancing Professional Development.

Those primary care practitioners who had successfully engaged in core supervision understood that the sharing of ideas positively affected change in practice and reported that it helped them to regulate their feelings and emotions and gave them a voice and sense of value in the work they undertook (Da Silva Pinheiro et al. 2014). Equally, Claridge et al. (2011) stated that by offering core supervision it increased good patient outcomes due to the compliance with managerial protocols and adherence to evidence-based practice.

Primary care staff can have the opportunity to explore cultural beliefs and values which gave a better sense of understanding and awareness of organisational goals, their professional needs and that of their patients (Snowdon et al., 2017). Also, it offered the practitioner to assess their social effectiveness, emotional intelligence and enhance self-awareness (Goleman, 2009). This helped practitioners to engage effectively and proficiently in their ‘day to day’ practice and gain more confidence and self-efficacy with the potential to improve workforce well-being and have the realisation of what value they have within their organisation (Hodge et al. 2023 and Walsh et al., 2021).

4.3 Competing demands and support from senior management

Supervision has been and is dependent on competing service demands and is frequently seen as not being a priority, particularly if there is insufficient staffing in busy clinical environments. Differences in clinical settings appeared to not only reflect organisational culture but also how easy it was to access the supervision. This was clearly demonstrated within the data.

A key challenge is examining and considering the organisational culture and attitude towards supervisory practice, particularly before setting up supervisory sessions (Churchill and Rashid, 2017). If there is an absence of managerial support and buy-in, there will be little motivation to embed supervision into the workforce culture (Akhigbe et al. 2017). This lack of commitment from organisations and managers has functioned as a barrier to providing the protected time and resources for effective supervision and leads to negative consequences around staff retention, wellbeing and patient care delivery and safety (Webb et al. 2015).

4.4 Becoming a supervisor and training

Lastly, there has been a long-standing challenge about the ability to formulate and facilitate core supervision sessions following training. Gonge and Buus (2010) have stated that the value and success in delivering structured supervision is dependent on the confidence of the supervisor. Also, a lack of quality in supervision processes and absence of guidelines for supervisors could risk confidentiality and professional ethical standards (Love et al. 2017). As it takes time to deliver and consolidate training, supervisors do require ongoing support and supervision to build confidence in facilitating the group work and the mechanisms to feedback into quality improvements for the organisation.

The utilisation of the ‘train the trainer’ model was introduced to speed up the implementation of core supervision in general practice. However, some participants felt there was a risk of diluting the consistency of core supervision (Triplett et al. 2020) and that the model would weaken the desired learning outcomes.

Equally, a lack of supervisory confidence through cascading knowledge and skills in delivering core supervision training via the ‘train the trainer’ model has been identified as a barrier to effective clinical supervision. This could be due to supervisors expressing a negative behaviour or feeling stressed that can affect the dynamic of the group session (Nancarrow et al. 2014). A consideration would be to look closely at the training content and potentially offer more advanced coaching, supervision group mechanisms, and better understanding around learning outcomes.

5.0 Discussion

The key outcomes indicates that primary care practitioners require protected time due to competing demands and require visible senior management ‘buy in’ to implement core supervision. Additionally, practitioners who had participated or supervised sessions felt the benefits on many areas of clinical practice but required more guidance and skill on becoming more effective in facilitating core supervision sessions.

Rodwell et al (2014) has stated that core supervision improves teamwork and relational dynamics, which leads to enhancing professional development and practitioner motivation. By developing a supportive working environment and shared understanding of workplace policies and procedures, this benefits the organisation delivery of care and helps practitioners to see the significance and rationale for implementation. However, to undertake this, a vital focus on protected time offers the opportunity of exploration of personal and professional issues based on the practitioners needs and growth rather than organisational demands (Redpath et al. 2015). By offering a ‘safe space’ to engage in evaluating aspects of clinical practice will pave ways forward with clarity and equanimity that benefits the organisation and the quality of delivered patient care (Wilson and Davies, 2016).

Workload can be discussed that often contributes towards occupational stress, anxiety, and burnout (Iosim et al., 2021) yet the challenge is that a structure and supportive network and supervision process is required for those delivering core supervision. However, there is no one size fits all when considering supervision training (Rothwell et al. 2021). All stakeholders need to consider ways to enhance the efficiency of their supervision and to do this successfully they need ongoing support as supervisors. Kingsley et al (2023) stated that a supervision training model adapted for community nurses demonstrated self-reported improvements in confidence and highlighted positive changes in staff attitudes and wellbeing. This is one attribute in assisting staff retention. Therefore, finding the right supervisory mechanisms may avoid the risk of dilution and thus suggests that train the trainer may not be the best format for disseminating training onwards.

Lastly, supervisors need to consider that some supervisees lack the ability to share feelings and thoughts through fear of reprisal creating frustration and professional stagnation (Henderson et al. 2015). Other practitioners have perceived supervision as being equated to surveillance (Love et al. 2017) and this could have been an indication from low response from the study. This can lead to a failure of cascading training and a demotivating factor for some supervisors in facilitating core supervision and ongoing training.

6.0 Limitations

There was a limited response rate but did pass the threshold of a small cohort size to give some confidence of the findings.

To run the survey completely anonymously, without recording any respondent details, no username or passwords were distributed, only a weblink. This was chosen as not to complicate access or expend time for the practitioner to request access and complete the survey, as the researchers were conscious that practitioners time was going to be prioritised to patient care. The survey availability was time limited to reduce the risk of a respondent completing the survey twice and only one reminder was sent in the four-week data collection period. Only one researcher held the participants list, who was one of the supervision trainers to the selected cohort. This tried to minimise bias and uphold confidentiality on analysis as the other two researchers did not know or participate in any of the respondents training prior to the survey distribution.

7.0 Recommendations

From the study the following key recommendations are considered a priority to assist in successful core supervision delivery in primary care settings.

- Encourage more senior buy in, which helps to foster more trusting relationships in a hierarchical work model and clarity on what objectivities and activities may benefit staff development, quality patient care and the organisational goals.

- Embed national and local strategies which will assist ongoing development and evaluation of core supervision and further research of Impact on staff wellbeing and engagement in the workforce.

- Standardised Learning Outcomes and Training in Supervision processes across the Yorkshire and Humber regions particularly around how to conduct a supervision session.

- Encourage supervisors to be more pro-active in engaging in protected time events.

- Continue to encourage drop-in sessions for continuous support and guidance for supervisors and develop an active nurturing community that fosters best practice and professional development.

8.0 Conclusion

As healthcare policies and regulations evolve, supervision practices are expected to adapt, and supervisors will need to ensure that practitioners are informed and compliant with the latest regulations and standards in primary care. This includes the ongoing trend towards continuous professional development the latest evidence-based practices within primary care settings.

The research findings suggest that further research on embedding core supervision within primary care with a focus on the national and local strategies are required. Standardised learning outcomes across the regions to ensure transferability of supervision into practice is consistent and review training in supervision processes, particularly around conducting a supervision session. This may help to develop a shared understanding to prevent barriers and challenges arising and an agreed purpose for core supervision to be successful in being embedded into practice.