Vitamin B12 deficiency is a condition that occurs around the world. Although more frequently seen in older adults, it can occur at any age and in any ethnic group and can affect both males and females alike, although there is some indication that women are more commonly affected than men and the condition tends to run in families. Symptoms can vary in severity ranging from mild to severe. Diagnosis can often be problematic as many of the symptoms patients present with are shared with other conditions and can easily be attributed to other causes. Some patients will also have folate deficiency and this aspect will be briefly covered as the two deficiencies can occur concurrently. This article aims to give practice nurses and nurse prescribers a better understanding of both conditions, and more confidence in diagnosing and treating their patients.

Role of B12 and folate in health

Vitamin B12 is vital for health and is essential for a number of physiological functions in the body, including the formation of healthy red blood cells, DNA synthesis and the healthy function of the nervous system and the brain. Folate has a similar role and is essential for the production of red blood cells, DNA and RNA synthesis, and is also important in helping to maintain brain function.

Vitamin B12 or folate deficiency anaemia occurs when a lack of B12 or folate causes the body to produce abnormally large red blood cells (NHS Choices, 2019). These larger cells have a decreased ability to carry oxygen, leading to anaemia.

B12 and pernicious anaemia

The most common cause of vitamin B12 deficiency in the UK is pernicious anaemia (an autoimmune disease), which accounts for 80% of cases and occurs as a result of impaired absorption of vitamin B12 (Knott, 2016). Other causes of B12 deficiency are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Other causes of vitamin B12 deficiency

| Cause | Additional information |

|---|---|

| Intestinal causes | Crohn's disease affecting the ileum, radiotherapy causing irradiation to the ileum, resection of the ileum, malabsorption |

| Drugs | Metformin, anticonvulsants, colchicine, neomycin |

| Drugs affecting gastric acid production | Long-term use of H2 receptor antagonists or proton pump inhibitors |

| Gastric causes | Helicobacter pylori infection, gastrectomy or gastric resection, gastritis or congenital deficiency of intrinsic factor |

| Dietary causes | Poor diet, vegan diet |

Prevalence rates

In the UK and the US the prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency is around 6% in people aged less than 60 years, rising to approximately 20% among people over the age of 60 years. This rises to an even greater prevalence among those over 70 years of age, with estimates suggesting that more than 10% of those in this age group may be affected. The prevalence of folate deficiency among adults and children is no more than 5% (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2019).

Pathophysiology

Vitamin B12 is obtained from a variety of food sources (Table 2) or from foods which have been fortified with it. In healthy people, the body stores 2–3 mg which is sufficient to last for approximately 2–4 years (Tidy, 2016). Parietal cells found in the lining of the stomach produce hydrochloric acid and intrinsic factor, both essential for B12 metabolism. The former allows B12 to be released from food, and the latter is vital for its absorption. Several factors can impede parietal cell function, including infection (such as with Helicobacter pylori) and the production of parietal cell antibodies or intrinsic factor antibodies (IFAB).

Table 2. Dietary sources of vitamin B12 and folic acid

| Food sources of vitamin B12 | Food sources of folic acid |

|---|---|

| Meat (lamb, chicken, beef, pork) | Brown rice |

| Salmon | Chickpeas |

| Cod | Asparagus |

| Milk | Broccoli |

| Eggs | Peas |

| Cheese | Brussel sprouts |

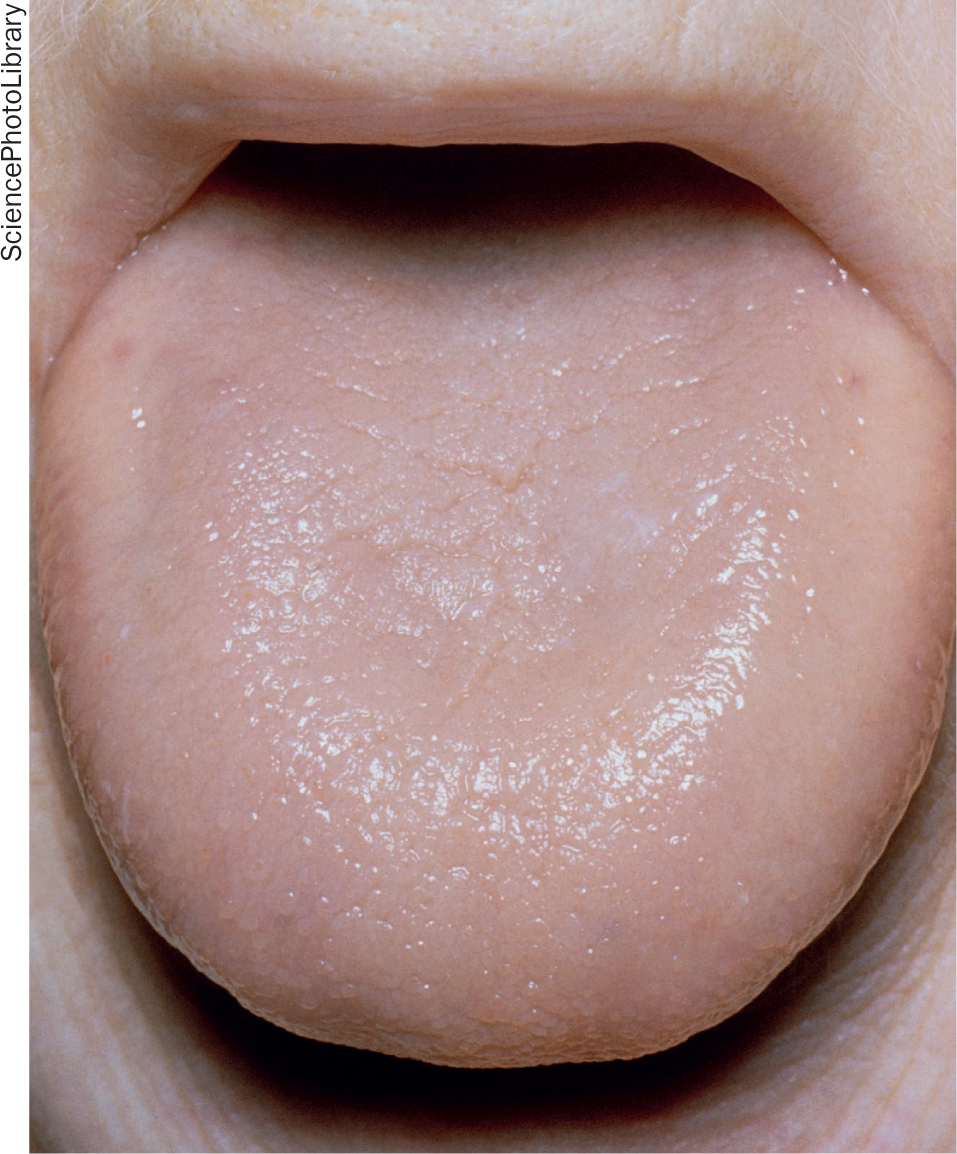

Figure 1. Close-up of a smooth tongue in a person suffering from pernicious anaemia

Figure 1. Close-up of a smooth tongue in a person suffering from pernicious anaemia

Parietal cell antibodies

Parietal cells are located in the lining of the stomach. If parietal cells fail or the body begins to produce antibodies against them, they are unable to function correctly and can therefore no longer produce intrinsic factor. However, the presence of parietal cell antibodies cannot be used to diagnose pernicious anaemia, because although around 80% of patients who have the condition will have parietal cell antibodies, around 10% of the general population will also have them (Pernicious Anaemia Society, 2019).

Intrinsic factor antibodies

Many people with pernicious anaemia produce intrinsic factor antibodies. These antibodies attack any intrinsic factor that has been produced by the parietal cells and render it useless. When this occurs, the lack of functioning intrinsic factor leads to an inability to extract vitamin B12 from any food source, leading to deficiency and the subsequent health issues that this will cause.

Folate deficiency

In some patients, folate deficiency occurs alongside B12 deficiency. It is unclear why deficiencies of the two occur together, as B12 is found only in animal foods and folate is found mainly in plant foods (Table 2). Unlike vitamin B12, body stores of folate are very low and are only sufficient to last around 4 months (Newson, 2016). The causes of folate deficiency are shown in Table 3. Dietary sources of both vitamins are shown in Table 2.

Table 3. Causes of folic acid deficiency

| Poor dietary intake (eg anorexia) |

| Old age |

| Malnutrition and alcohol excess |

| Malabsorption (coeliac disease, inflammatory bowel disease) |

| Poor social conditions |

Signs and symptoms

Signs and symptoms of B12 deficiency tend to have an insidious onset and some patients may not develop any symptoms that trouble them until their deficiency is severe. Tiredness and lethargy are typical symptoms of anaemia, and in addition the patient may complain of paraesthesia, a sore glossy tongue and mouth ulcers. Findings on examination may include pallor, heart failure (if anaemia is severe), lemon tinge to the skin, and in addition there may be neuropsychiatric features including irritability, depression, psychosis and dementia (Tidy, 2016). In severe cases the patient may also develop sub-acute combined degeneration of the spinal cord and peripheral neuropathy. In contrast, symptoms of folate deficiency occur much more rapidly and are very similar to those experienced with B12 deficiency, making it difficult to determine the cause of the patient's symptoms without further investigations.

Investigations

There is currently no gold standard test to define deficiency and it is therefore very important to get a detailed clinical history and assessment so that blood test results can be correlated to aid diagnosis. The standard test used is assessment of serum B12 levels (serum cobalamin), which is evaluated alongside folate levels because of the close relationship between the two and the risk that both may be reduced.

Full blood count

A raised mean cell volume (MCV), which refers to the average volume of a red blood cell, is a common finding, which may occur with or without a low haemoglobin level. However, it is not specific for B12 deficiency and clinicians would need to exclude other causes such as excess alcohol intake, drugs and myelodysplastic syndrome (Tidy, 2016). Similarly, a normal MCV cannot be used to exclude testing for B12 deficiency, as 25% of patients with neurological impairment will have a normal MCV (Tidy, 2016). In some patients where dietary deficiency or a condition causing malabsorption is the cause, blood test results will also show iron deficiency.

Blood film

A blood film test showing hypersegmented neutrophils (more than 5% of neutrophils with five or more lobes, or one or more neutrophils with 6 or more lobes) and the presence of oval macrocytes, may suggest either vitamin B12 or folate deficiency, but their presence is not sensitive or specific in early B12 deficiency (NICE, 2019). The blood film may also show neutropenia and thrombocytosis (Hunt et al 2014). Other investigations that can be requested are shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Additional investigations

| Investigation | Additional information |

|---|---|

| Plasma total homocysteine (tHcy) | This is a sensitive marker of B12 deficiency, but is not specific and can be raised in other conditions. A major drawback is that specimens need to be tested within 2 hours of collection |

| Plasma methylmalonic acid (MMA) | Raised in B12 deficiency, but the high cost of this test has limited its widespread use |

| Holotranscobalamin | This test is thought to be more specific than serum cobalamin levels. It has the advantage that it can be stored for batch analysis, and may in the future become the recommended first-line test, if research confirms its accuracy and the cost is acceptable |

| Bone marrow examination | Much less widely used now but may still be needed if the diagnosis is in doubt and a differential diagnosis such as myelodysplasia, aplastic anaemia, myeloma, or other marrow disorders is suspected |

Interpreting results

Vitamin B12 level

Interpretation of B12 levels is extremely difficult as there is no clinically normal level (NICE, 2019), although it has been suggested that a serum cobalamin of <148 pmol/litre (200 ng/litre) would have a sensitivity of 97% in the diagnosis of true B12 deficiency (Devalia et al, 2014). Blood results may not always correlate with patients' symptoms, although it is likely that those with very low B12 levels will have clinical features of deficiency. Women taking oral contraceptives may show decreased cobalamin levels because of a decrease in cobalamin carrier protein, although this may not result in deficiency (NICE, 2019).

Folate level

Folate levels can similarly be difficult to assess, although it is generally accepted that a level of below 7 nanomol/litre (3 micrograms/litre) is indicative of deficiency (NICE 2019). Borderline levels can also occur, complicating things further. If serum levels are normal but deficiency is suspected, red cell folate can be used to make the diagnosis in the event of normal B12 levels.

Sub-clinical results

For those with a borderline B12 level, guidelines suggest a repeat test in 1–2 months (guidelines may vary at different laboratories). For a number of patients, values will return to normal and no further action will be needed. However, in the event that results remain within the ‘sub-clinical’ range, guidelines suggest a blood sample should be taken for anti-IFAB and a short trial of empirical therapy (oral cyanocobalamin 50 mg daily for 4 weeks) should be given while awaiting results of the IFAB test (Devalia et al, 2014). In reality, many patients who remain in the sub-clinical category and who appear to be symptomatic, will go on to commence treatment as per UK guidelines.

Treatment and management

NICE guidance (2019) gives specific advice on treatment and management of B12 and folate deficiency. For patients with no neurological involvement treatment includes:

- Intramuscular hydroxocobalamin 1 mg on alternate days for 2 weeks

- For those whose deficiency is not diet-related, intramuscular hydroxocobalamin should continue as above at 2–3 monthly intervals for life

- In those where diet is thought to be a cause, they can either be treated with oral cyanocobalamin tablets (50–160 mcg tablets daily) or have a twice yearly hydroxocobalamin injection.

For patients with neurological involvement specialist advice is advised. However, if is not immediately available, or the patient would not be able to attend an appointment, it is recommended that the health professional administer hydroxocobalamin 1 mg intramuscularly on alternate days until there is no further improvement, then administer hydroxocobalamin 1 mg intramuscularly every 2 months (NICE, 2019). Dietary advice about foods that are a good source of vitamin B12 should also be given if diet is thought to be a cause of deficiency (NICE, 2019).

Treating folate deficiency

Folate deficiency can be corrected by giving 5 mg of folic acid daily for 4 months in adults (or until term in pregnant women), and up to 15 mg daily may be required in those whose deficiency is caused by malabsorption (Newson, 2016). NICE (2019) recommend checking vitamin B12 levels in all people before starting folic acid, as treatment can mask underlying B12 deficiency, and allow neurological disease to develop.

Complications

Potential complications of B12 deficiency include (NHS Choices, 2019):

- Increased risk of stomach cancer in those with pernicious anaemia

- Memory loss

- Fertility problems (reversible with treatment)

- Vision problems

- Loss of co-ordination.

Potential complications of folate deficiency include (NHS Choices, 2019):

- Fertility problems (reversible with treatment)

- Increased risk of cardiovascular disease

- Increased risk of some cancers (eg bowel cancer)

- Increased risk of premature birth in pregnancy

- Increased risk of neural tube defects in pregnancy.

Prognosis

Before advances in medicine, deficiencies of both B12 and folate could potentially lead to long-term problems, and in the case of B12 deficiency, it could result in a fatal outcome (Kerkar, 2018). This is no longer the case and early detection and treatment allows the majority of those affected to live a normal life with no long-term adverse effects. The only exception is for patients who have suffered a severe deficiency of B12 and have developed neurological complications. These may unfortunately not be reversible (NICE, 2019).

Conclusion

Given the high prevalence of this condition, practice nurses and nurse prescribers will almost certainly be involved in the recognition and care of patients who develop B12 and folate deficiencies. Early recognition and treatment are essential if long-term damage is to be avoided. Practice nurses can play an essential role in getting patients diagnosed and treated early, before complications set in. It is hoped that this article has enhanced knowledge and understanding of the conditions discussed and will give readers more insight and confidence enabling them to request investigations so that treatment can be initiated and quality of life can be maintained.

KEY POINTS:

- Vitamin B12 and folic acid are essential for a number of physiological functions in the body and can be obtained from a variety of food sources

- Signs and symptoms of B12 deficiency have an insidious onset and some patients may not develop any symptoms that trouble them until their deficiency is severe. In contrast, symptoms of folic acid deficiency occur much more rapidly

- There is currently no gold standard test to define deficiency and it is therefore very important to get a detailed clinical history and assessment so that blood test results can be correlated to aid diagnosis

- Treatment of both deficiencies allows the majority of those affected to live a normal life with no long-term adverse effects

CPD reflective practice:

- What are the signs and symptoms of B12 and folate deficiencies?

- Which investigations would you order in a patient with symptoms of B12 deficiency?

- In a patient with sub-clinical results, how would you proceed?