Practices nurses are an important part of a multidisciplinary team and are involved in most aspects of patient care including health screening, sexual health screening, helping patients manage long term conditions, contraception and women's health, including cervical cytology and menopause management. Therefore, for many women, they are the first potential point of contact regarding sexual and reproductive concerns. Barriers identified by healthcare professionals for not discussing sexual issues are related to a ‘lack of time, personal discomfort, lack of training and worry it will cause offence’ (Dyer and das Nair, 2013). For those who assert they are embarrassed or lack experience, it has been shown that these barriers are of less concern in those who perform such consultations daily or weekly compared to those who do so infrequently (Temple-Smith et al, 1999). In the UK, availability of NHS provision for specialist menopause centres, psychosexual input and specialist pelvic physiotherapists varies widely, so practice nurses should be encouraged and supported to help their patients address any sexual health concerns.

What is female sexual dysfunction?

Female sexual dysfunction (FSD) can affect women of any age and the causes are varied and complex. Perhaps the most widely adopted diagnostic criteria for female sexual dysfunction are contained in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). In 2013, the classification of female sexual desire disorder and female arousal disorder was re-named female sexual interest/arousal disorder, dyspareunia was revised to genital/pelvic pain and vaginismus was replaced with penetration disorder. Female orgasmic disorder was unchanged. Interest and research into female sexual health, sexual response, sexual difficulties and treatment interventions has grown steadily over the past two decades. These include Dr Rosemary Basson's model of female sexual response (Basson, 2000), the research by Lori Brotto on the use of mindfulness to improve sexual distress (Brotto, 2015) and Amy Stein on the role of the pelvic floor in pelvic pain (Stein, 2009).

Sexual interest/arousal disorder

DSM-V definition

The DSM-V definition of sexual interest/arousal disorder is (American Psychiatric Association, 2013): a complete lack of, or significant reduction in, sexual interest or sexual arousal occurs 75–100% of the time, causes personal distress and has been present for a minimum of 6 months. The problem may be primary (lifelong) or secondary (acquired), situational or generalised.

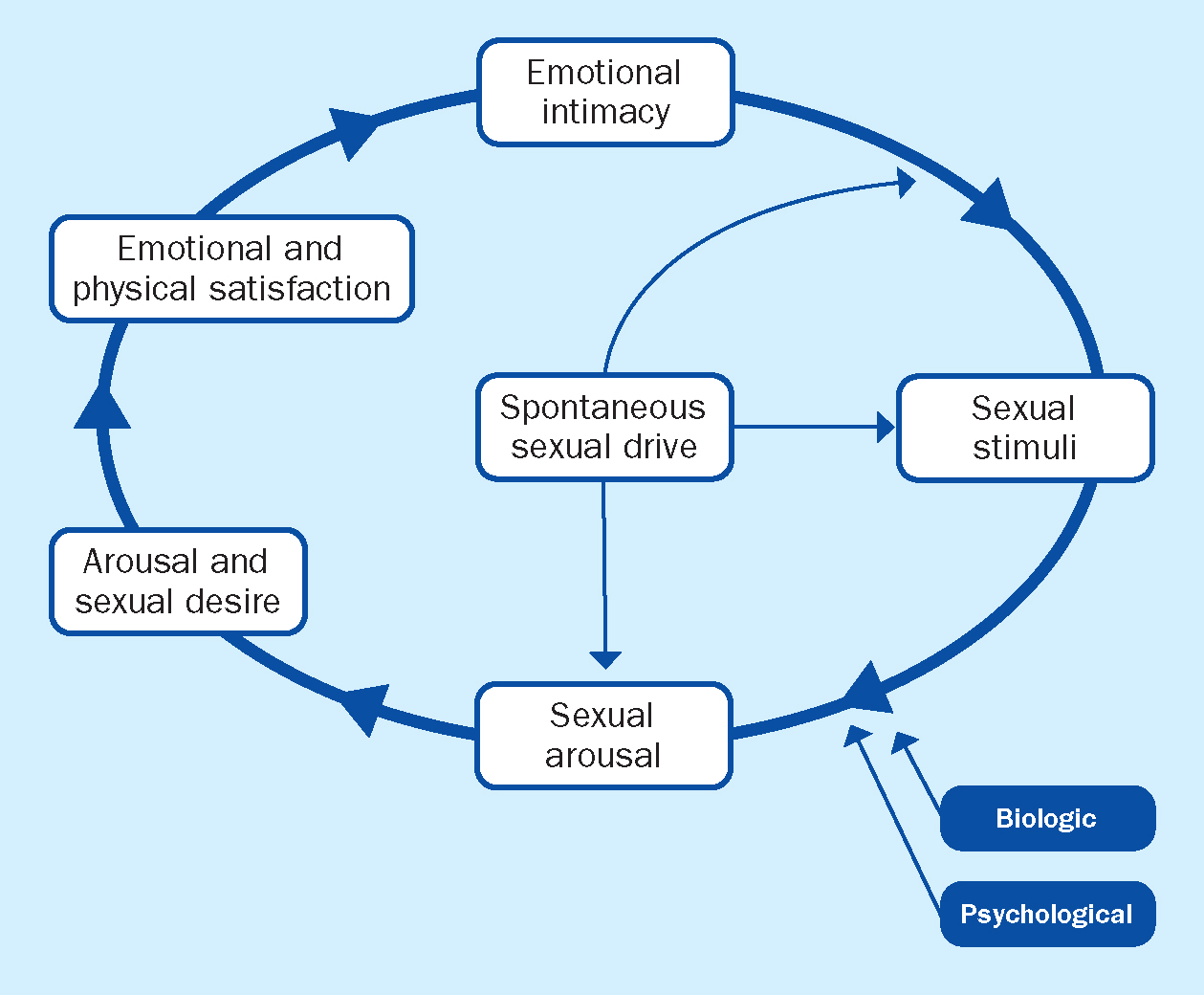

If addressing complaints of little or no spontaneous sexual interest or desire, it is important to first consider Basson's (2000) model of female sexual response (Figure 1), which acknowledges that many women in established relationships feel little ‘spontaneous desire’. Her model suggests that if women are willing to seek out or be receptive to sexual stimuli and if there are no negative psychological or biological barriers, they may then experience sexual arousal and only then do they experience sexual desire. Thus, a lack of spontaneous desire or sexual interest is not in itself dysfunctional.

The key messages in Basson's (2000) model are:

- Women's desire is often experienced as responsive and can be triggered by being receptive to sexual stimuli

- Spontaneous desire/interest is more common in younger women and at the beginning of relationships and becomes more variable as women age and relationships progress

- Multiple biological factors can impact on a women's sexual response and inhibit sexual desire/interest and arousal.

Factors associated with problematic sexual desire/interest and arousal include biological, relationship and emotional issues. Biological factors can impact directly on a woman's sexual function, eg vaginal dryness, pelvic floor dysfunction, thus making it difficult to experience either spontaneous or responsive desire, or indirectly, such as chronic pain or medication that interferes with the physiology of the central and peripheral sexual response and the psychological consequences of being ill (Kirana, 2013). Conditions such as urinary incontinence, diabetes, arthritis, spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, hyper- and hypothyroidism are associated with sexual difficulties. Various medications have also been associated with low desire and problematic arousal, including anti-hypertensives, anticholinergics, psychotropic drugs and combined oral contraceptives (Kirana, 2013). Treatment for sexual interest/arousal difficulties can be complex, often dependent on a thorough assessment and examination. Helpful interventions in a primary care setting could be routine blood tests – including thyroid function – checking blood pressure, screening for diabetes and identifying any vaginal or urogenital symptoms related to hormonal changes.

Basson's model can be used to ‘normalise’ experiences related to changes in sexual response. Box 1 provides some resources that may help with this.

Box 1.Resources for normalising changes in sexual response

- Women could be directed to www.omgyes.com to explore the latest science on female sexual pleasure and arousal

- The sexual temperament questionnaire by Emily Nagoski can be downloaded at www.emilynagoski.com

- For those with long-term health conditions who experience inhibition or distress due to their physical limitations or illness, Enhance The UK has a ‘love lounge’ that provides free advice on sex, love and disability: www.enhancetheuk.org

- If difficulties engaging sexually are related to relationship issues then a referral to a psychosexual or relationship therapist may be required and a list of local therapists and details of what psychosexual therapy involves can be found at: www.cosrt.org.uk or www.relate.org.uk

- A directory of therapists in the UK who identify as, or are understanding of, gender, sex and relationship diverse people can be found here: www.pinktherapy.com

- Helpful factsheets, videos and an app are available from: www.sexualadviceassociation.co.uk.

When starting a conversation it is important to consider the key points below (Rantell, 2021):

- Use neutral and inclusive terms such as ‘partner’ and pose your questions in a non-judgemental way

- Avoid making assumptions based on a person's age, appearance, marital status or any other factor. Unless you ask you cannot know a person's sexual orientation, behaviours or gender preference

- Ask for preferred pronouns or terminology when talking to a transgender person.

Opening questions when discussing this topic with patients could include:

- ‘Could you describe the sexual difficulties you're having?’

- ‘It would be really helpful for me to ask you some personal questions so that I can fully understand what you are describing. This would help me to know what to suggest and where I could refer you. Is that okay?’

Genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder (dyspareunia and vaginismus)

DSM-V definition

One of the following should occur persistently or recurrently to establish a diagnosis (American Psychiatric Association, 2013): difficulty in vaginal penetration; marked vulvovaginal or pelvic pain during penetration or attempt at penetration; fear and anxiety about pain in anticipation of, during or after penetration; and tightening or tensing of pelvic floor muscles during attempted penetration. It must cause personal distress, be present on 75–100% of occasions and have been present for at least 6 months.

Pain is often multifactorial and can be caused by vaginitis, Bartholin gland abscess, episiotomy scarring, sexually transmitted infections, pelvic inflammatory disease, endometriosis, prolapse or vaginal dryness. Therefore, it is essential that all women are given the opportunity to be examined to determine or exclude any underlying pathology. Sexual/genital pain can also be caused by inhibition due to body image concerns, reduced sexual desire/interest and arousal, infrequent sexual intercourse, extensive penetration/thrusting and pelvic floor dysfunction. Questions related to previous treatments and what benefit they had, if any, are important. For example, some women treated for post-menopausal vaginal atrophy with local hormonal or non-hormonal vaginal treatment may report a lack of benefit as they continue to experience pain and discomfort. However, this may be related to a lack of sexual interest/arousal, anxiety about penetration with its negative impact on sexual response and pelvic floor muscle dysfunction, as each could potentially be the cause of continued vaginal discomfort after treatment (van der Velde and Everaerd, 2001).

Menopause matters

Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) is the updated terminology for vulvo-vaginal atrophy, which describes more accurately the urogenital changes and the local symptoms occurring after the menopause. It involves clinical symptoms and signs from both the genital and lower urinary tract, associated with the decreased hormone levels that can involve the labia minora/majora, vestibule/introitus, clitoris, vagina, urethra and bladder (Portman et al, 2014). GSM affects up to 50% of postmenopausal women and 70% of breast cancer survivors (Mac Bride et al, 2010; Parish et al, 2013; The North American Menopause Society, 2013), with women spending up to 40% of their lives postmenopausal. It is a chronic and progressive condition, which unless treated is unlikely to improve over time. Common sexual complaints, such as vaginal dryness and painful sex, should be routinely assessed in clinical practice in order to preserve quality of life across the aging process, especially in surgically or medically induced menopausal women, in whom sexual symptoms may be more distressing (Caruso and Malandrino, 2013). Lower urinary tract symptoms of frequency, urgency, dysuria and recurrent urinary tract infections have also been widely reported. These can cause personal distress, reduce quality of life and impact negatively on sexual pleasure (Nappi et al, 2007; Avis et al, 2018). When examining a patient with GSM it may be necessary to use a smaller speculum due to possible introital narrowing, vaginal shortening and lack of elasticity of the vagina (Flint and Davis, 2021).

Treatments

Expert opinion recommends non-hormonal vaginal lubricants and moisturisers, as well as on-going sexual activity, as a first line treatment for symptomatic vaginal dryness and atrophy (North American Menopause Society (NAMS), 2007). These products help re-hydrate the vagina and can be used alongside a lubricant. Silicone-/oil-based lubricants make penetration more comfortable and are less likely to dry up than water-based products. Regular intercourse provides protection from atrophy by increasing the blood flow to the pelvic organs (Lev-Sagie and Nyirjesy, 2000). However, painful intercourse is difficult to sustain; therefore, it is essential that women are educated on the benefits of lubricants and moisturisers. Low dose vaginal oestrogens are second-line treatments and are highly effective, especially for GSM-related painful sex. Local oestrogen is preferred if vaginal dryness is the primary concern, and systemic oestrogen for features of menopause such as hot flushes, mood changes or bone changes (Suckling et al, 2006; Basson et al, 2010; North American Menopause Society, 2013).

Opening questions when discussing this topic with patients could include:

- ‘After the menopause some women experience sexual or urinary discomfort – is this something that you have noticed or would like to discuss?’

- ‘I am going to ask you a few questions about your sexual history. I ask these questions at least once a year of all my patients because they are important for your overall health. Everything you tell me is confidential. Do you have any questions before we start?’

Pelvic floor dysfunction

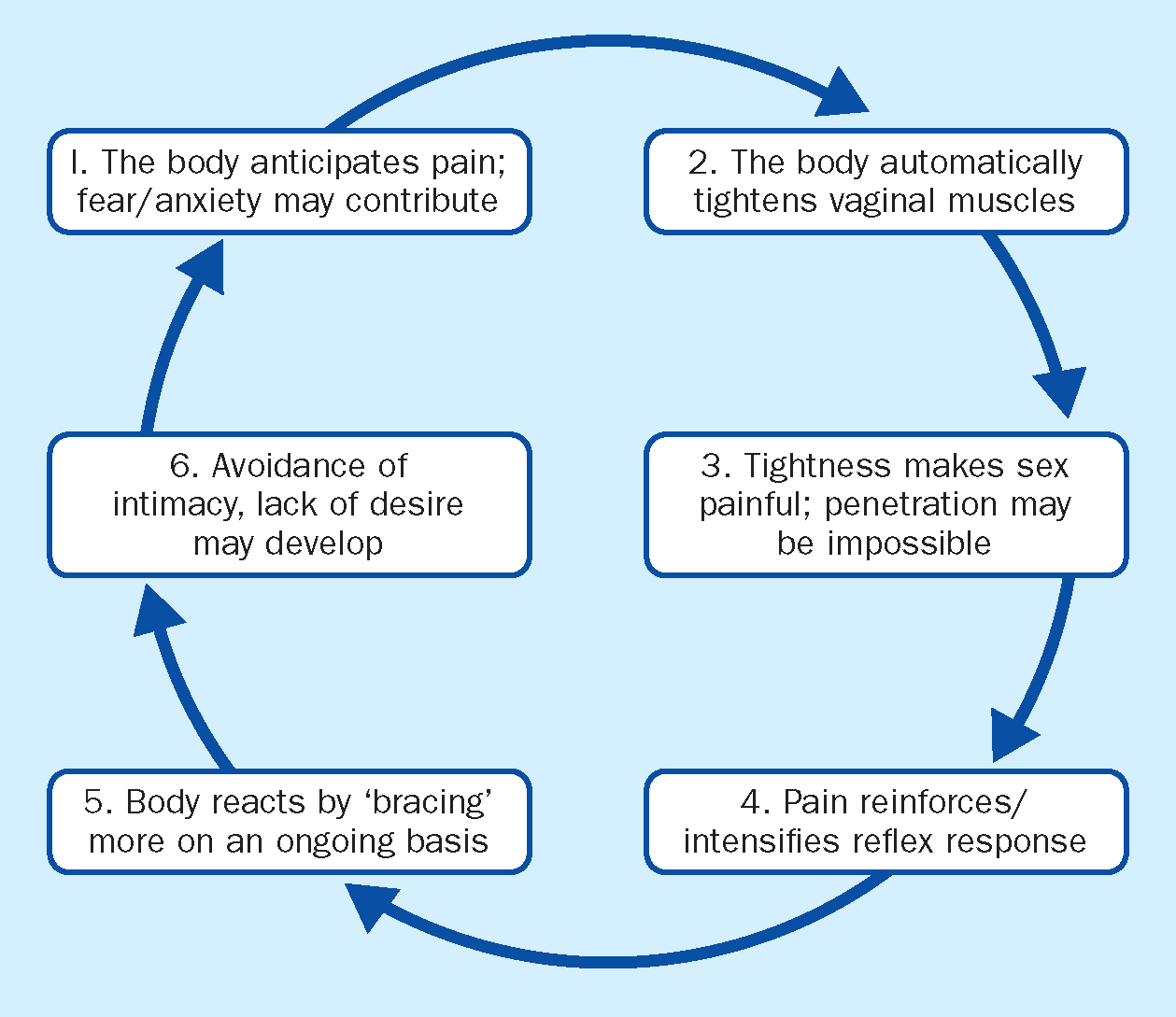

Pelvic floor dysfunction describes any muscular issue in the pelvic area, which includes both weak and tight muscular symptoms. It is a term applied to a wide variety of clinical conditions, including incontinence, urinary tract infections, pelvic organ prolapse and several chronic pain conditions. Women with GSM and sexual pain may have dysfunctional pelvic floor muscles that become tense or tight because of ongoing vaginal dryness and discomfort or pain with sexual activity (Rosenbaum, 2010; Faubion and Rullo, 2015). Pelvic floor muscle hypertonicity has been demonstrated to contribute to interstitial cystitis (Peters et al, 2007), provoked vulvodynia (Reissing et at, 2005) and generalised vulvodynia (Glazer et al, 1998). Genital pain may also trigger pelvic floor dysenergia (van der Veld and Everaerd, 2001). Studies have demonstrated that pelvic floor muscle hyperactivity is a part of an overall response to heightened anxiety (FitzGerald and Kotarinos, 2003). In the author's experience there are several reasons why some women struggle to tolerate an internal examination or cervical cytology and display high levels of distress:

- They have never had vaginal penetration or used tampons

- They are scared it will be painful

- Previous negative or traumatic experiences related to examinations, sexual activity or childbirth

- Long term history of genital/sexual pain.

The cycle of pain (Figure 2) can help women understand why pelvic floor muscle hyperactivity can be the source of their pain or involved after they have experienced pain due to other comorbidities.

Treatment

Treatment for issues with genital/sexual pain is dependent on the cause and underlying pathology. If pelvic floor dysfunction is identified then the following should be encouraged:

- Information and exercises for strengthening and maintaining a healthy pelvic floor (for women with a normal or weak pelvic floor); this is especially important for those who suffer from incontinence or prolapse (Stuart, 2021). There are a number of apps that remind women to do their exercises regularly (eg www.squeezyapp.com)

- Women with a tense or tight pelvic floor should be signposted to stretching and relaxing exercises (Stein, 2009).

Women not able to consciously relax their pelvic floor muscles during examination or sexual activity may require specialist pelvic physiotherapy, psychological or psychosexual input, and those with a weak or damaged pelvic floor unresponsive to pelvic floor strengthening exercises may need to be referred to a specialist pelvic physiotherapist, incontinence clinic or urogynaecology.

For those with genital pain that is unrelated to sexual activity or pelvic floor hyperactivity, then referral to a specialist vulval clinic or dermatology may be necessary. When any underlying pathology has been treated or the issue with pain is related to an unrelaxing pelvic floor and fear of pain, graded exposure and systematic desensitisation could be suggested, which includes the use of vaginal dilators. This can be very useful in cases when phobic responses are ‘triggered’ when a stimulus is present. The stimulus here would be vaginal insertion, whether with a penis, finger or speculum. It has been used in the treatment of genital/sexual pain as well as those suffering from generalised fears of penetration (Kirana, 2013). There are very few studies regarding the use of vaginal dilators, even though they are a well-established treatment option (Smith and Gillmer, 1998; Goldstein, 2000; Lev-Sagie and Nyirjesy, 2000).

For women who have undergone pelvic radiotherapy, trans women and women without a partner or those who have experienced long periods of sexual abstinence, the use of vaginal dilators or a vibrator can help restore sexual self-confidence, manage anticipatory anxiety related to pain/penetration and maintain vaginal integrity when used alongside a lubricant and moisturiser. Those who have been prescribed vaginal dilators without success need a detailed assessment of how these were used and what guidance, instruction or support was provided. Diaphragmatic breathing exercises should be taught, as inserting a dilator on a long, slow out-breath makes insertion easier and focusing on frequency of use rather than size is more likely to build confidence.

Opening questions that could be used include:

- ‘I know we didn't manage to do your smear (or examination) today, I could see you that you found it very difficult but you did really well. Has that happened before?’

- ‘I noticed that you really struggled when I opened the speculum during your cervical examination, do you experience similar difficulties with penetrative sex or in your sexual relationship?’

Box 2.Recommended readingSexual interest/arousal disorder:

- Mind the Gap by Dr Karen Gurney – The truth about desire and how to futureproof your sex life

- Mating in Captivity by Ester Perel

- Come as you are by Emily Nagoski – The surprising new science that will transform your sex life

Genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder

- www.newsonhealth.co.uk – Contains everything you need to know about the menopause and its treatments

- www.breastcancercare.org – UK's leading charity for those affected by breast cancer

- www.isswsh.org – A multi-disciplinary, academic and scientific organisation that provides the public with accurate information about women's sexuality and sexual health

- Me and my menopausal vagina by Jane Lewis – One women's frank and honest journey of her menopausal vagina

Pelvic floor dysfunction

- Sexual Function and pelvic floor dysfunction. Rantell A (ed) – A guide for nurses and allied health professionals

- Heal Pelvic Pain by Amy Stein – The proven stretching, strengthening and nutrition program for relieving pelvic pain, incontinence, IBS and other symptoms without surgery

- The Body Keeps The Score by Bessel van der Kolk – Mind, brain and body in the transformation of trauma

- In An Unspoken Voice by Peter Levine – How the body releases trauma and restores goodness

- www.jostrust.org.uk – The UK's leading cervical cancer charity with helpful suggestions for women undergoing cervical cytology screening

Conclusion

Sex is good for our physical and mental health and is a vital part of most relationships, but for those unfamiliar, talking about sex and sexual function can be daunting. However, providing women with the opportunity to talk about sexual problems is a fundamental part of healthcare (Nappi and Lachowsky, 2009). Practice nurses have a unique role in providing an opportunity for early discussion, education and treatment of sexual difficulties, especially those related to GSM and pelvic floor disorders. Having knowledge of specialist services and practitioners in the local area and specific referral criteria pathway is essential alongside the recommended online help and resources.

CPD REFLECTIVE PRACTICE:

- How confident do you feel discussing problems with sexual dysfunction? What could make you more confident?

- Think about a patient that finds cervical screening difficult. Had you previously considered how sexual dysfunction/pelvic pain might affect this? How would you tackle this issue in future?

- How will reading this article change your clinical practice?

KEY POINTS:

- Practice nurses have a unique role in the early discussion and detection of sexual problems

- A lack of spontaneous desire is normal for many women

- The silent symptoms of the menopause can negatively impact on sexual function

- Recognising the role and impact of pelvic floor dysfunction is essential